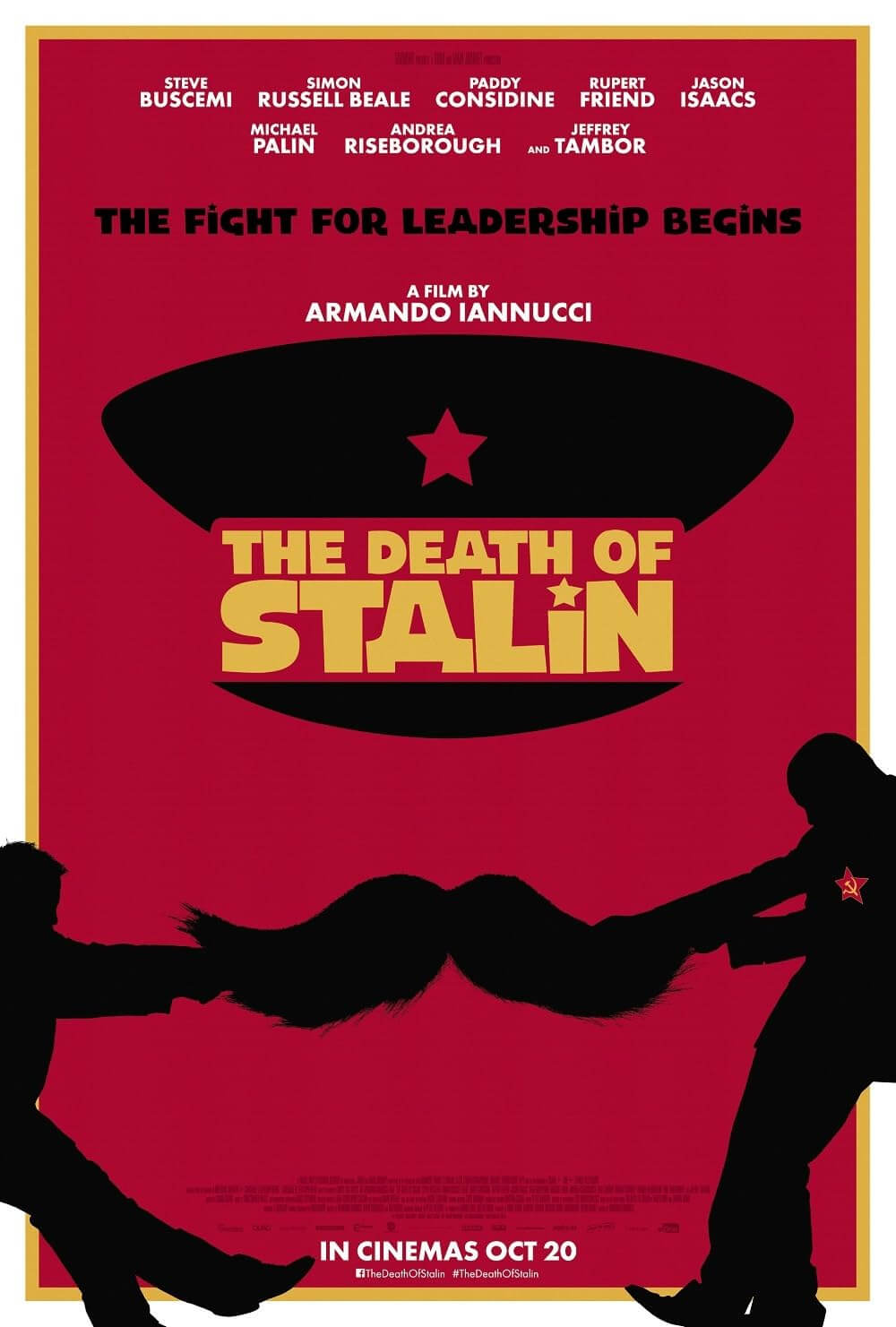

The Death of Stalin

By Brian Eggert |

The Death of Stalin opens with a sequence that perfectly articulates its exploration of how fear leads to the absurd. In the Stalinist Soviet Union of 1953, during a concerto broadcast over Moscow radio, pianist Maria Yudina (Olga Kurylenko) plays a selection from Mozart. At the same time, a radio programmer (Paddy Considine) receives a call from Joseph Stalin himself, played Adrian McLoughlin. With strict orders to call Stalin back in precisely 17 minutes, the programmer scrambles to determine whether the countdown started 30 seconds or a minute ago, fearing that if he should return the call late, he will be another name on the totalitarian ruler’s dreaded kill lists. When he eventually calls back, the programmer gets instructions to have a recording of the performance ready for pickup, which is a simple request, except the concert wasn’t recorded. Thinking fast, the programmer convinces the orchestra and pianist to play again for Stalin’s recording, this time with louder applause from an audience he wrangles off the street. Compelled by a desperate fear, he completes the recording, which is delivered to Stalin, who never hears it. Yudina included a harsh note along with the recording, and upon reading it, Stalin collapses.

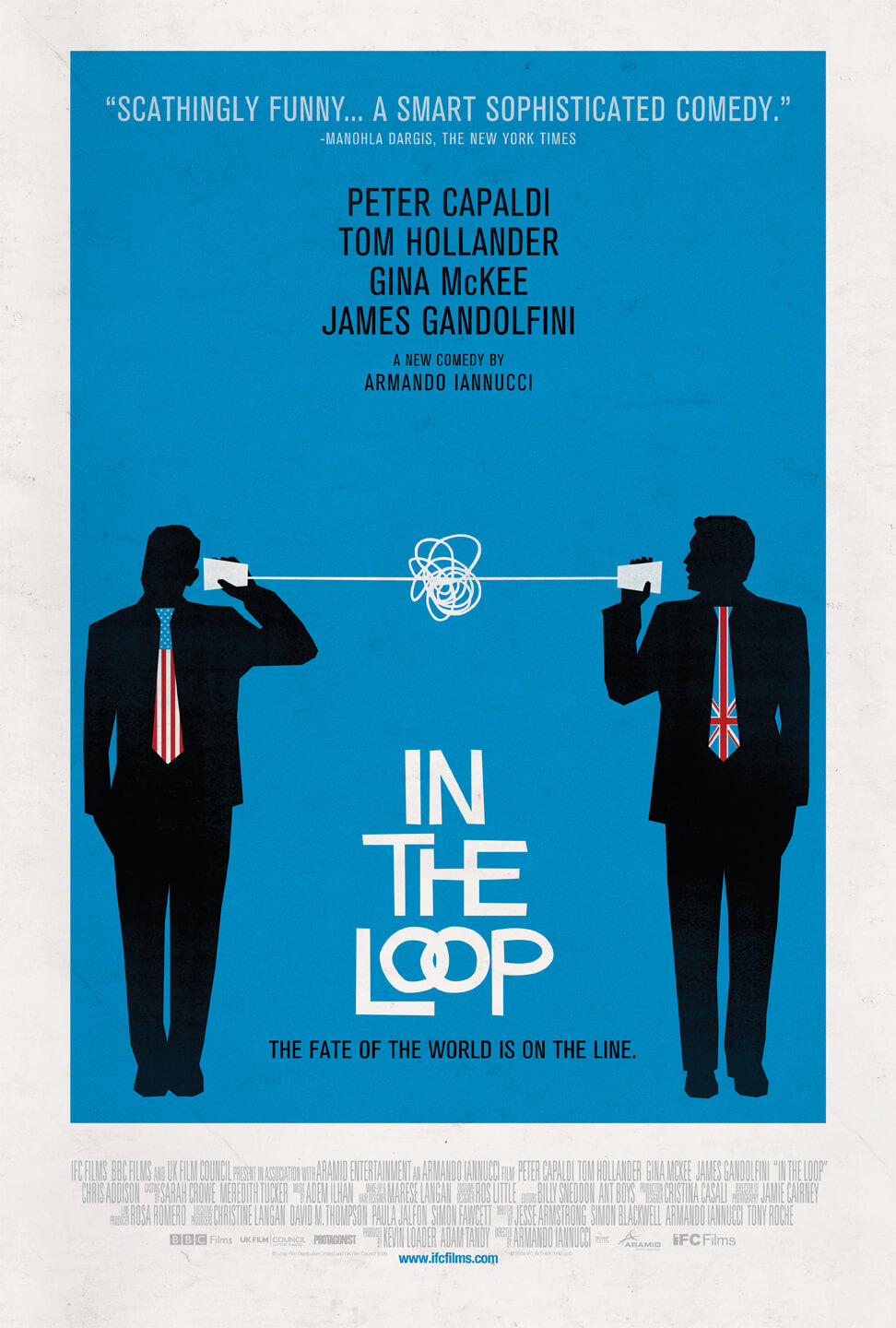

Merciless and riotously funny, The Death of Stalin transforms the authoritarian regime into a site for macabre humor, often twisting one of history’s most genocidal eras into the punchlines of a scathing comedy. Armando Iannucci’s film blends actual history with an equal dose of fictionalized satire, condensing and reordering history to turn the most outlandish factual accounts into broad-spectrum humor composed of acidic British wit, slapstick, and political parody. Getting his start in British television, the Glasgow-born Iannucci is best known for the BBC’s The Thick of It (2005-2012), its cinematization In the Loop (2009), and HBO’s Veep (2012-still going strong), though not in that order. He also co-created Alan Partridge alongside Steve Coogan, making him something of a treasure to all of humanity. With The Death of Stalin, Iannucci finds eerie relevance in the material, namely in the inherent danger and horror that occurs from blindly towing the party line amid political chaos.

Based on graphic novels by Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin, the film shows Chairman Stalin basking in the adulation of his Council of Ministers until, at last, he topples over from a cerebral hemorrhage in his country dacha, facing certain death. Even with their leader unlikely to wake, his counsel remains fearful of saying anything that he might hear, just in case he regains consciousness and seeks reprisals. Stalin’s inner circle consists of Deputy Chairman Georgy Malenkov (Jeffrey Tambor), an assured dope and next in line to the throne; Nikita Khrushchev (Steve Buscemi, outstanding), a chair on the council and most sensible hyena in the pack; the ousted Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov (Michael Palin); and the repugnant Lavrentiy Beria (Simon Russell Beale), head of the NKVD secret police and administrator of the Gulag. Stalin’s seniormost acolytes vie for primacy over the regime in anticipation of his death, while also fumbling amid the remnants of their leader’s bureaucracy. Of course, these men have carried out Stalinism’s worst crimes, including a daily routine of mass killings and arrests. Rooting for any of them becomes a thorny prospect. Nonetheless, Beria, a serial rapist—who kisses Stalin’s hand one moment, cheers the instant he thinks Stalin has died and then cowers again when it turns out he’s still breathing—presents a compelling villain of the bunch.

Iannucci’s approach to history is fast and loose, not that he disguises it. His cast doesn’t bother with a faux Russian cadence and, instead, they speak in their original accents. Buscemi and Tambor’s American contrasts the British inflection of the others, while the later appearance of Jason Isaacs as Marshal Georgy Zhukov, a hunk of scar tissue and testosterone heading the Russian army, might represent the sole performative accent in a rough South Yorkshire brogue. Along with the detailed production design by Cristina Casali, which renders a believable 1950s Soviet atmosphere, and the period-accurate costumes by Suzie Harman, The Death of Stalin has a curious counterbalance of accuracy and inflection, making its intent as satire unmistakable. But some of the most unbelievable events and behaviors on display in the film actually took place in some form. For instance, as Stalin lies on the floor in a puddle of his own urine, the Council debates about where to find a doctor. “If only we hadn’t put away all those doctors for treason,” says Beria, who rounded up predominantly Jewish doctors in Moscow, blaming an alleged plot to kill Stalin. Whether it’s Beria’s frightening logic in the most pandemonious situations or the frenzied scheming that never stops, much of their behavior seems unbelievable and hilariously nonsensical in the darkest ways. As one of them says resignedly, “I’ve had nightmares that have made more sense.”

Iannucci’s approach to history is fast and loose, not that he disguises it. His cast doesn’t bother with a faux Russian cadence and, instead, they speak in their original accents. Buscemi and Tambor’s American contrasts the British inflection of the others, while the later appearance of Jason Isaacs as Marshal Georgy Zhukov, a hunk of scar tissue and testosterone heading the Russian army, might represent the sole performative accent in a rough South Yorkshire brogue. Along with the detailed production design by Cristina Casali, which renders a believable 1950s Soviet atmosphere, and the period-accurate costumes by Suzie Harman, The Death of Stalin has a curious counterbalance of accuracy and inflection, making its intent as satire unmistakable. But some of the most unbelievable events and behaviors on display in the film actually took place in some form. For instance, as Stalin lies on the floor in a puddle of his own urine, the Council debates about where to find a doctor. “If only we hadn’t put away all those doctors for treason,” says Beria, who rounded up predominantly Jewish doctors in Moscow, blaming an alleged plot to kill Stalin. Whether it’s Beria’s frightening logic in the most pandemonious situations or the frenzied scheming that never stops, much of their behavior seems unbelievable and hilariously nonsensical in the darkest ways. As one of them says resignedly, “I’ve had nightmares that have made more sense.”

Elsewhere, Stalin’s daughter Svetlana (Andrea Riseborough) arrives and incites a competition between Beria and Khrushchev, each trying to gain the favor of their leader’s beloved offspring. They’re less interested in her brother Vasily (Rupert Friend), a reckless and trigger-happy drunk. When Stalin eventually dies, Malenkov assumes his position and, in doing so, becomes a puppet—with Beria pulling the strings on his girdle. It’s appropriate, then, that Tambor’s makeup gets thicker and his lips darker, as Malenkov prepares himself for photo opportunities by donning the look of a silent film star. Khrushchev and Beria quickly try to align Malenkov with their own interests, knowing the weak replacement cannot last. The Council assigns Khrushchev the unhappy task of arranging a funeral for Stalin, while Beria continues to make impulsive, or perhaps devilishly calculated political moves, knowing that amid the ensuing chaos, he can seize power for himself. Meanwhile, the members of Stalin’s Council on the outer orbit—Lazar Kaganovich (Dermot Crowley), Anastas Mikoyan (Paul Whitehouse), and Nikolai Bulganin (Paul Chahidi)—flow with the tide, their loyalties determined by whoever resides in power.

Iannucci’s inspired casting places certain actors into familiar roles. He borrows from HBO’s ranks to cast Buscemi as Khrushchev, who recalls the actor’s Nucky Thompson from Boardwalk Empire. Tambor plays Malenkov as dimwitted and egomaniacal, bringing to mind his thick-headed sidekick Hank Kingsley from The Larry Sanders Show. Palin has an opportunity for Brazil-esque speech as Molotov, as his character explains his loyalties in twisted logic to an increasingly frustrated Council: “I have always been loyal to Stalin. Always. And these arrests were authorized by Stalin. But Stalin was always loyal to the collective leadership. That is true loyalty. But he had an iron principle, undeviating, strong. Shouldn’t we do the same, and stick to what we believed in? No. It’s stronger still to forge one’s own beliefs into the beliefs of collective leadership… Which I have now done.” The wordsmithing of such a speech is equally funny and impressive.

To be sure, The Death of Stalin occupies a distinctly British humor (as opposed to a Russian sensibility), combining wit and absurdity in deadpan notes, yet through a Brechtian delivery system that never allows the viewer to forget they’re watching satire. The screenplay by Iannucci, Nury, David Schneider, Ian Martin, and Peter Fellows feels whole, or at least as much as something rooted in political disorder chaos can attain cohesiveness. Scenes alternate between Iannucci’s biting humor and brutally funny insults (“You’re not a person, you’re a testicle!”), and the grim realities of Stalin’s USSR. There are brief glimpses inside the Gulag with emaciated prisoners and point-blank executions; citizens shot down in the streets by the NKVD; and perhaps least funny of all, during Beria’s eventual execution, the details of his sex crimes read aloud, his victims listed in the hundreds, at ages as low as 7-years-old—a detail followed by Beria’s corpse burning in a gruesome image. The brilliance of Iannucci’s limber tonal shifts is that he can switch between them in an instant, keeping a sharp audience on edge, while never losing our investment in the film.

The Death of Stalin was written and shot before Trump took office, though it cannot help but reflect our current cult of personality surrounding the celebrity-turned-President, a figure allegedly controlled by Russian interests. Certainly, it’s enough if the film occupied nothing more than a historical satire, lampooning the anxieties and ridiculous behavior that actually occurred around Stalin’s deathbed and funeral with an appropriate amount of artistic license. But perhaps it also reveals how life around an authoritarian leader, inevitably, gives way to moral gray areas out of sheer self-preservation, linking Stalin’s distinctly hypermasculine court to that of Trump. In his depiction of power’s absurdity, Iannucci may have (unintentionally, and yet unapologetically) revealed what the reported chaos in the White House must be like, with self-interested parties carrying out ludicrous requests that, at the moment, seem justified. For today’s audiences, the film demonstrates how towing the party line with blind complicity leads to a gross distortion of ideology until the only ideology is obedience.

Although The Death of Stalin initially secured a license for exhibition in Russia, officials in their Culture Ministry balked at the film’s humor toward their history and banned the film, not only in Russia but in several other countries that were part of the former Soviet Union. Among other things, the Culture Ministry took aim at the film’s portrayal of Zhukov, given his heroic place in Russian culture for winning the Battle of Stalingrad against the Nazis—a victory that has emboldened the current streak of nationalism that seems to validate similar Stalinist crimes in Russia today. Laughter might be the only way to process contemporary political hysterics around the globe, and Iannucci delivers a wry sense of historical irony. The Death of Stalin‘s comically circular structure brings us back to the opening scene’s concert hall in the last shot, with Khrushchev having seized power and Leonid Brezhnev behind him, waiting for his moment. If nothing else, the film reassures, through laughter and historical relativity, that every power-mad leader soon meets their end.

(Editor’s Note: Review updated to reflect Jason Isaacs’ South Yorkshire, not Cockney, accent.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review