The Dead Zone

By Brian Eggert |

In the early 1980s, David Cronenberg had just finished work on Videodrome and was already fully aware of his own growing status as an auteur, a writer-director filmmaker with a personal style and set of reoccurring themes through which he told his stories. His succession of bodily horror titles such as They Came from Within, Rabid, The Brood, and Scanners solidified this notion with critics and horror aficionados alike. And yet, after the exhausting, evacuating creative experience that had been writing, filming, and releasing Videodrome earlier in 1983 to an unenthusiastic commercial response and split assessment from critics, Cronenberg wanted to challenge himself not by tapping into his own creative pipeline once more, but by taking a project that was not of his own devising and place his personal stamp on it. So when he was approached by producer Debra Hill, who was partnered with legendary producer Dino De Laurentiis, to make a film version of Stephen King’s 1979 novel, The Dead Zone, he immediately signed on.

Even before its release, Cronenberg’s film of King’s novel was received with disappointment and skepticism. Videodrome’s immeasurable aesthetic vision had set his followers’ expectations high. With the announcement of his new project, it seemed as though Cronenberg left behind his directorial signatures concerning the body for a pointedly Hollywood project—if only because King adaptations had been assigned such a reputation. Two months before The Dead Zone opened in October, Lewis Teague’s version of Cujo had earned a moderate profit. In December of that year, John Carpenter’s underrated adaptation of Christine would hit theaters, though neither was well received. However, as history would show, films based on King’s books neither guaranteed success nor a quality product, although their trend began promisingly enough. Brian De Palma’s breakthrough with Carrie (1976) would become a landmark of the horror genre, as would Stanley Kubrick’s liberally adapted but brilliant epic The Shining (1979)—both superb experiments in style and tone. A 1979 television miniseries based on Salem’s Lot also earned plenty of attention.

All were successful commercial projects, and Cronenberg’s involvement in yet another King adaptation, for many, signaled his crossover into mainstream filmmaking. Only after 1983 would King adaptations become suspect; titles like Firestarter (1984), Cat’s Eye (1985), Silver Bullet (1985), and Pet Sematary (1989) would each become disappointing films. The Dead Zone was received with lukewarm reviews, and even among Cronenberg’s most devoted fans, the film is considered a sidestep in his progression from his deeply personal origins for The Brood to his grand conceptual realization in Videodrome—the combination of which would lead to his masterpiece, The Fly (1986). Indeed, The Dead Zone seems constructed as an alternative to Cronenberg’s usual brand of story. His characters are, by and large, urban dwellers with elaborate names like Bianca O’Blivion and Daryll Revok and Murray Cypher, deeply involved in their own sexuality and decidedly apolitical and non-religious. In contrast, this film follows Johnny Smith, a simple teacher from rural Maine who restrains his sexuality, is surrounded by God-fearing characters, and, in time, takes action based on his politically influenced beliefs.

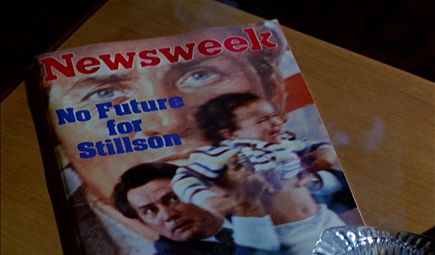

Still, as Cronenberg worked closely with screenwriter Jeffrey Boam, very Cronenbergian themes emerged even though the director himself did none of the writing. During the film’s long development, several scripts were considered by the producers. Stephen King himself completed a draft, whereas Polish director Andrej Zulawski also turned in a script. Still, Cronenberg noticed how they each distanced the audience from the story by taking an objective approach. They viewed a story in which “normal guy” Johnny Smith (to be played by Christopher Walken) gets in a car accident, spends five years in a coma, and wakes up with precognitive, psychometric powers from no perspective at all. In the story, Johnny touches someone’s hand and jerks into reality-bending visions that, for the character, blur the line between this moment and the next. He uses his abilities to stop (among other incidents) the “Castle Rock Killer” and prevent political candidate Greg Stillson (Martin Sheen, over-the-top and fantastic) from inciting a nuclear war as president. But each proposed script told the story by emphasizing the killer or Stillson, allowing for unnecessary slasher or torture scenes that Cronenberg saw no place for in his adaptation.

Still, as Cronenberg worked closely with screenwriter Jeffrey Boam, very Cronenbergian themes emerged even though the director himself did none of the writing. During the film’s long development, several scripts were considered by the producers. Stephen King himself completed a draft, whereas Polish director Andrej Zulawski also turned in a script. Still, Cronenberg noticed how they each distanced the audience from the story by taking an objective approach. They viewed a story in which “normal guy” Johnny Smith (to be played by Christopher Walken) gets in a car accident, spends five years in a coma, and wakes up with precognitive, psychometric powers from no perspective at all. In the story, Johnny touches someone’s hand and jerks into reality-bending visions that, for the character, blur the line between this moment and the next. He uses his abilities to stop (among other incidents) the “Castle Rock Killer” and prevent political candidate Greg Stillson (Martin Sheen, over-the-top and fantastic) from inciting a nuclear war as president. But each proposed script told the story by emphasizing the killer or Stillson, allowing for unnecessary slasher or torture scenes that Cronenberg saw no place for in his adaptation.

But rather than writing the script himself, in a sense, he directed Boam on what scenes to omit or include, and how to change this or that character to tell the story that Cronenberg wanted to tell. For example, in the book, before his accident, Johnny is ostensibly engaged to his longtime sweetheart, Sarah (Brooke Adams); but after waking from his coma, he finds that she’s married and has a young child. Johnny recoils from society after his publicized “second sight” garners unwanted attention when his visions save a child from burning up in a fire. As he’s unable to teach in any public capacity, he serves as a tutor for a wealthy young man named Chuck. Cronenberg changes this detail in the film to make the story more affecting: To emphasize Johnny’s emotional response, Cronenberg had Boam change the blond-haired, Corvette-driving Chuck into the reserved, emotionally withdrawn preteen named Chris (Simon Craig), who for Johnny represented the son he never had with Sarah. In this respect, the audience would come to better relate to Johnny as a broken man—someone who once was certain of his own life and future, until something disastrous befell him, and he became an outsider in his own story. That sense of isolation is what Cronenberg and Boam draw out in the script and what endures as the film’s most engaging quality.

Adjusting seemingly minor details—such as switching Chuck to Chris or decreasing the presence of and perspective away from the “Castle Rock Killer” and Greg Stillson—makes the film more and more Cronenbergian, but in very subtle ways. Consider Johnny’s condition in the book, which emerges after an ice-skating accident and from the oft-used King device of a brain tumor (as explained away in the epilogue). In the book, Johnny’s precognitive abilities show their first signs when he’s a young boy, and as his tumor grows, so do his abilities. The book features the same car accident, but his skill for precognition has already revealed itself in slight ways. Long after Johnny awakes from his coma, he learns that he will eventually die of his brain tumor, and, with nothing to lose, this is when he determines to become an assassin before Stillson can incite a nuclear holocaust. At a rally, Johnny waits on a balcony for Stillson to appear. He fires but misses, and Stillson grabs a baby during the commotion and holds it up as a human shield. Johnny is shot down by bodyguards, but the photographs taken of Stillson using a baby for protection effectively ruin his political career. Cronenberg and Boam keep the assassination idea but omit everything else.

Adjusting seemingly minor details—such as switching Chuck to Chris or decreasing the presence of and perspective away from the “Castle Rock Killer” and Greg Stillson—makes the film more and more Cronenbergian, but in very subtle ways. Consider Johnny’s condition in the book, which emerges after an ice-skating accident and from the oft-used King device of a brain tumor (as explained away in the epilogue). In the book, Johnny’s precognitive abilities show their first signs when he’s a young boy, and as his tumor grows, so do his abilities. The book features the same car accident, but his skill for precognition has already revealed itself in slight ways. Long after Johnny awakes from his coma, he learns that he will eventually die of his brain tumor, and, with nothing to lose, this is when he determines to become an assassin before Stillson can incite a nuclear holocaust. At a rally, Johnny waits on a balcony for Stillson to appear. He fires but misses, and Stillson grabs a baby during the commotion and holds it up as a human shield. Johnny is shot down by bodyguards, but the photographs taken of Stillson using a baby for protection effectively ruin his political career. Cronenberg and Boam keep the assassination idea but omit everything else.

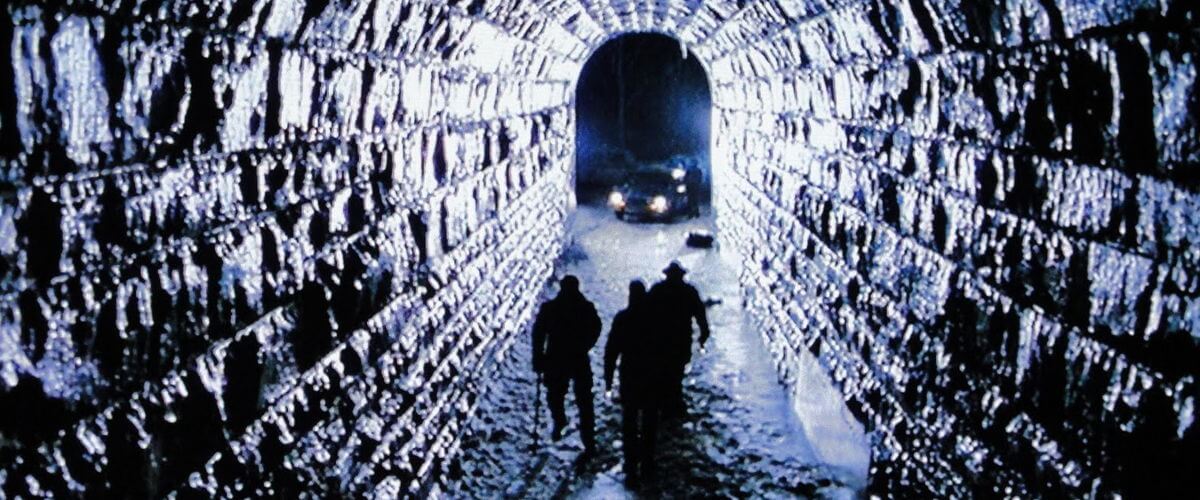

Although the idea of a brain tumor might seem to appeal to Cronenberg, whose frequent use of disease as a physical signifier of a psychological malady has informed so many of his films, he chooses to broaden the connection between Johnny’s gift (or curse, as he initially sees it) and his physical condition. In the film, rather than gradually developing over time, his precognitive visions only occur after waking from his five-year coma following the car accident. The trauma of this singular incident, which has so dramatically shaped his life and left him alone, is the sole instigating factor in Johnny’s ability. Johnny is plagued by visions, and in each, he sees a blank spot, or “dead zone,” that offers a possibility for an alternate future, leaving Johnny to take action and stop his vision from occurring. Nevertheless, with each vision, Johnny’s physical state deteriorates. The effects of his accident have ruined his emotional life and slowly tear away at his body, weakening him—a point articulated when, before his accident, Johnny gives his class their last assignment, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, a story about a teacher haunted by a headless demon. Indeed, his condition behaves like a disease contracted from his trauma and now eats away at him, a thoroughly Cronenbergian plot point.

The understated gradations and hurt behind Walken’s performance emphasize how Johnny suffers from a trauma-induced disease. When Johnny first appears before the accident, Walken’s hair is flat and rounded; large glasses widen the shape of his face, which always seems to hold a smile. After the accident, Walken appears without glasses, his face pale and bony, his eyes darkened, his hair thrown up and back as if zapped by an electrical jolt. Walken breathes complexity into Johnny Smith by smiling at strange, ironic moments. The character is acutely aware that his life has become some kind of experiment gone wrong in the hands of what Cronenberg has called “God the scientist” (paraphrased) or a joke of Nature. Moreover, this is one of Walken’s finest roles, brimming with intensity and nuance, and ushering one of the only instances in any Cronenberg film where the audience might feel their heartstrings tugged upon. Walking about with a cane like some Frankenstein monster, Walken slams aside a glass dish with his cane in a fit of rage or gestures with his hand to stay away in a moment of intense heartbreak, and the audience feels every emotion. It’s a performance that enhances every scene in an emotionally charged film.

Though Stephen King purists will argue that Cronenberg changes too many plot details for the film to be considered an accurate reproduction of the novel, King himself has noted that changes made by Cronenberg capture the spirit of the novel with great attention to character and emotion. On several occasions, King has named it among his favorite films based on one of his books. However, even if Cronenberg captured the novel’s spirit, that spirit didn’t help capture audiences or convince the majority of critics at the time. The film’s position within Cronenberg’s career felt pointedly out of place then, with its conspicuous lack of extreme metaphors—the fleshy makeup effects and grotesque physical revolutions that had been so common in his work thus far. But isn’t a physical trauma that gives way to a psychic one also an extreme metaphor and a prevalent theme in Cronenberg’s oeuvre?

Though Stephen King purists will argue that Cronenberg changes too many plot details for the film to be considered an accurate reproduction of the novel, King himself has noted that changes made by Cronenberg capture the spirit of the novel with great attention to character and emotion. On several occasions, King has named it among his favorite films based on one of his books. However, even if Cronenberg captured the novel’s spirit, that spirit didn’t help capture audiences or convince the majority of critics at the time. The film’s position within Cronenberg’s career felt pointedly out of place then, with its conspicuous lack of extreme metaphors—the fleshy makeup effects and grotesque physical revolutions that had been so common in his work thus far. But isn’t a physical trauma that gives way to a psychic one also an extreme metaphor and a prevalent theme in Cronenberg’s oeuvre?

In the years after its release, the film stood out in Cronenberg’s career as a peculiarity given its shortage of gory images—and especially considering its placement after Videodrome and before The Fly, two of his most elaborately graphic pictures. But today, The Dead Zone compares best to Cronenberg’s more recent films, those that may not rely on body-transforming metaphors yet involve deeply moving stories and characters, with his usual attention on the relationship between the physical and psychological always present nonetheless. In a way, The Dead Zone is precognitive, in that it falls in line next to later Cronenberg titles like Spider, A History of Violence, Eastern Promises, and A Dangerous Method as one of his most perceptive and complex dramas. And now, after the release of his more recent string of purely dramatic, arguably mainstream films, the director’s longtime devotees have accepted that Cronenberg’s auteurism extends into realms far beyond mere bodily horror despite their supposed commercialization. With this in mind, it’s time to revisit The Dead Zone and celebrate it for the sophisticated tale it is.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review