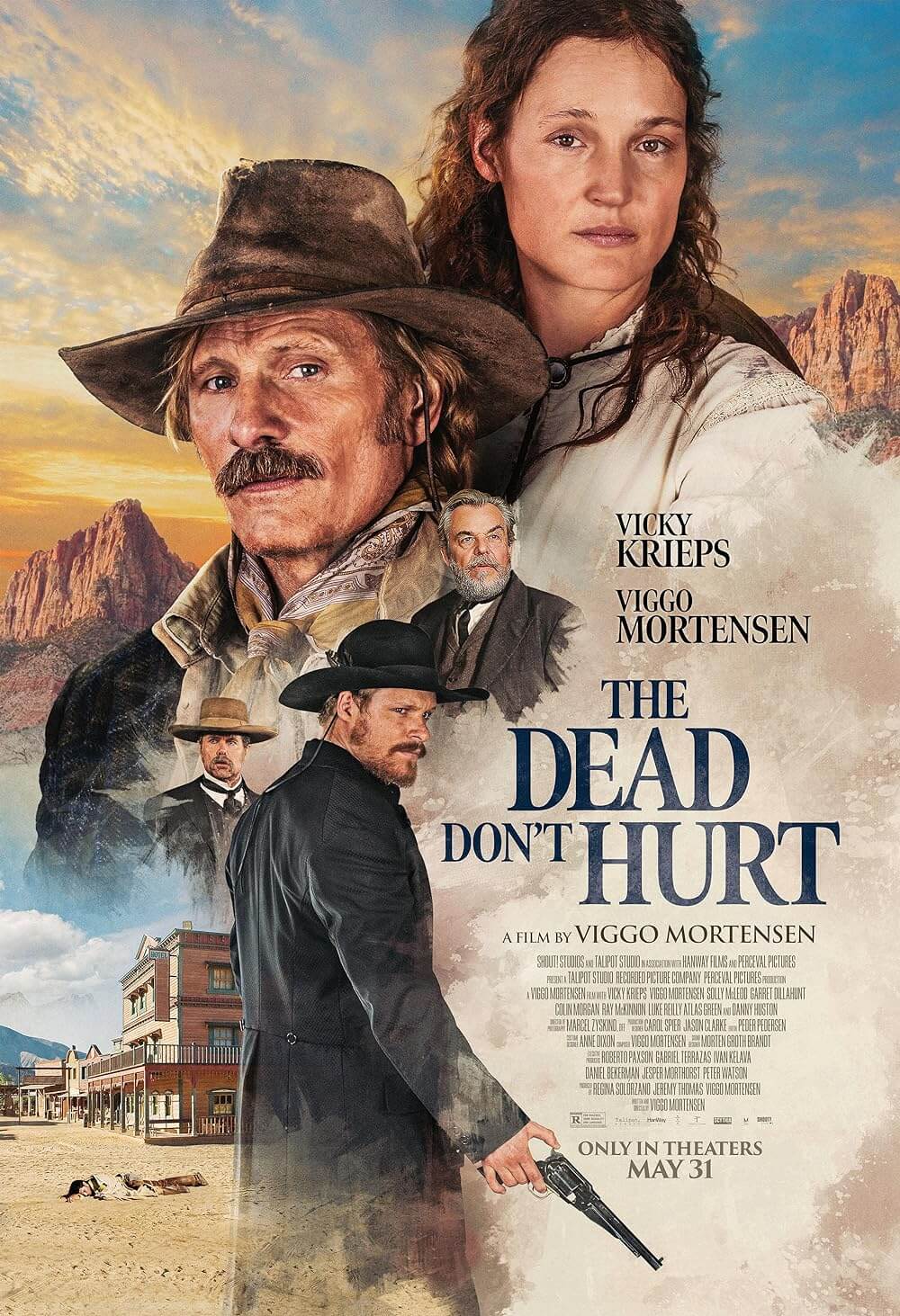

The Dead Don’t Hurt

By Brian Eggert |

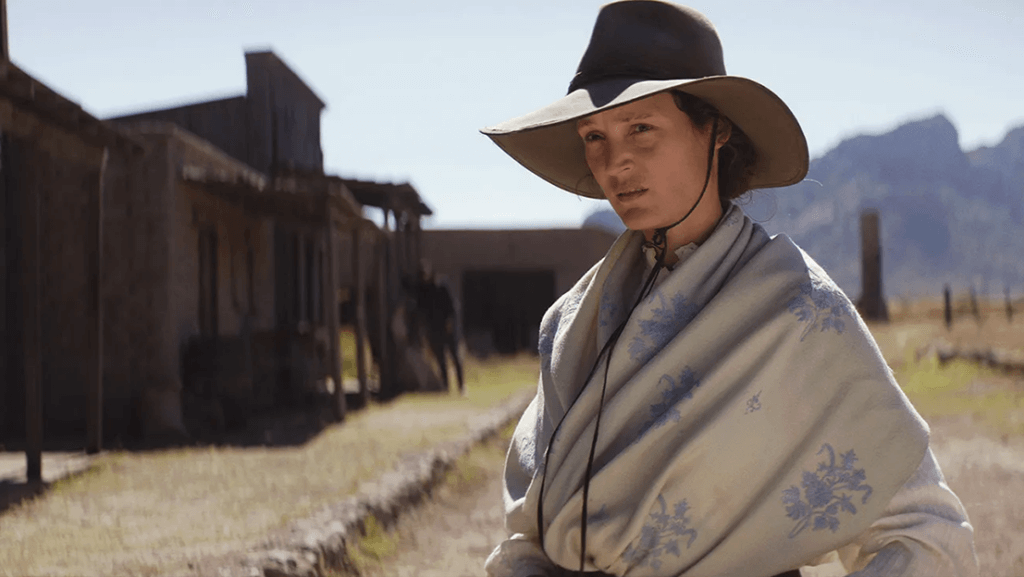

A spare and pensive Western, The Dead Don’t Hurt opens with the image of its lead, Vivienne, played by Vicky Krieps in another stunning performance, on her deathbed. An image flashes in her mind from a child’s perspective. Somewhere in the woods long ago, a knight emerges on a horse, clad in armor and carrying a flag. It’s the last thing on her mind when she passes. The source of her reverie won’t become apparent until much later in the film, but it’s essential to understanding her identity. Director Viggo Mortensen returns to this image throughout the film, his second, beautifully crafted feature, for which he also receives credit as screenwriter, composer, and co-lead, playing Vivienne’s lover. Mortensen structures its narrative in a novelistic, almost musical fashion; he arranges scenes in non-chronological order, offering a patient, lovingly told, and character-driven story. His film supplies a showcase for superb acting and the quiet poetry of its creator’s vision. And while he might have rearranged the events in a linear manner to service a typical scenario involving a do-gooder on a mission of revenge, Mortensen has more on his mind than a typical Western programmer or even a revisionist alternative. Rather, The Dead Don’t Hurt is meditative and mature filmmaking that at once embraces and rethinks classical Western motifs in a series of elegant, subtle alterations.

No stranger to the genre, Mortensen has played cowboys and gunslingers before in Young Guns II (1990), Hidalgo (2004), and Appaloosa (2008). He’s an apparent fan of the genre and populates his ensemble with familiar Western faces. Consider just the performers in Mortensen’s film who also appeared in Deadwood (2004-2006): Ray McKinnon, who played the tragic preacher on that HBO show, cameos as a local judge in one scene; W. Earl Brown, known as Al Swearengen’s right-hand, Dan, plays the bartender; Garret Dillahunt, who had a couple of roles on Deadwood, appears as Alfred Jeffries, a powerful and corrupt businessman. Elsewhere, Danny Huston plays the mayor in Mortensen’s film, though he’s unforgettable in John Hillcoat’s The Proposition (2005), a savage and fly-ridden Western from Australia. Besides Westerns, there’s also the influence of Mortensen’s several collaborations with David Cronenberg to consider, such as using Cronenberg’s regular production designer Carol Spier or casting his Crimes of the Future (2022) costar Nadia Litz in a small role. In front of and behind the camera, The Dead Don’t Hurt feels like a passion project, developed and made with a personal, hand-crafted quality that enriches the experience beyond today’s impersonal corporate projects dominating the multiplexes.

Set in the 1860s, the story begins in San Francisco with a French-Canadian woman, Vivienne Le Coudy. Initially courted by a presumptuous, well-to-do member of society (Colin Morgan), Vivienne remains far too independently minded to be the decoration on someone’s arm. Perhaps that’s why she’s drawn to the rugged Dane, Holger Olsen (Mortensen), a former soldier turned carpenter. He greets her with kindness and equality and, after they form an effortless bond, invites her to make a life with him at his isolated home on the frontier, near Elk Flats, Nevada. Both immigrants committed to making America their new country, Vivienne and Holger start a life of shared intimacy and self-reliance. She cleans out his filthy house, makes plans for a garden, and gets a job bartending in town. He builds barns for the resident fatcat, Jeffries. However, their time together is short, as Holger, having significant military experience (presumably in the Three Years’ War), enlists in the Union Army to fight against slavery. While another, more conventional film might follow Holger to battle, The Dead Don’t Hurt settles on Vivienne, who, after a teary goodbye, must survive alone.

Much of the focus remains on Vivienne in Holger’s absence. Almost immediately, she endures a common threat faced by women left to fend for themselves during the Civil War. Jeffries’ brash and murderous son, Weston (Solly McLeod), co-owner of the bar where Vivienne works, pursues and eventually rapes her. While this might be a typical Western situation, few films have dealt with the long-term psychological and physical impact; it’s more often a plot device to prompt the male hero into action. But Mortensen uses the incident to build Vivienne’s strength and resolve. She becomes pregnant and has a young boy, Vincent (Atlas Green), whom Holger gradually becomes a father to upon his return and appointment as sheriff. Later, she learns Weston gave her syphilis, the cause of her death, and venereal disease is a reality seldom addressed in Westerns. On the periphery, the film establishes Weston as an impulsive murderer, while both his father and the mayor conspire to protect him in their plans to develop their “shithole” town into something even more lucrative.

Much of the focus remains on Vivienne in Holger’s absence. Almost immediately, she endures a common threat faced by women left to fend for themselves during the Civil War. Jeffries’ brash and murderous son, Weston (Solly McLeod), co-owner of the bar where Vivienne works, pursues and eventually rapes her. While this might be a typical Western situation, few films have dealt with the long-term psychological and physical impact; it’s more often a plot device to prompt the male hero into action. But Mortensen uses the incident to build Vivienne’s strength and resolve. She becomes pregnant and has a young boy, Vincent (Atlas Green), whom Holger gradually becomes a father to upon his return and appointment as sheriff. Later, she learns Weston gave her syphilis, the cause of her death, and venereal disease is a reality seldom addressed in Westerns. On the periphery, the film establishes Weston as an impulsive murderer, while both his father and the mayor conspire to protect him in their plans to develop their “shithole” town into something even more lucrative.

Mortensen structures his film across three timelines, intercutting among them to rethink the conventional Western narrative. A more typical film with the same plot may have been a revenge story, following a lawman who sets out to avenge his wronged wife. Instead, Mortensen is more contemplative. Several passages involve Vivienne as a child (Eliana Michaud), learning about Joan of Arc from her mother (Véronique Chaumont) and wondering if her father will ever return home from war—a feeling that returns when Holger leaves for the Civil War. The young Vivienne asks her mother if women, too, fight wars. “Not in the same way,” her mother explains, foreshadowing Vivienne’s struggles later in life. Much of the story entails Vivienne and Holger’s courtship and time together, which could only have been encouraged initially by his horse’s name, Knight. Another thread follows Holger after Vivienne’s death, so grief-stricken that he turns in his sheriff’s badge and sets out with Vincent to find Weston. Mortensen moves among these timelines, recalling Stanley Kubrick’s edict that film should be an almost musical “progression of moods and feelings” rather than a strict set of plot points, orchestrating a rich narrative song that would feel less powerful and overly classical if arranged in chronological order.

The story feels old-fashioned in the events it portrays, yet it aligns with a modern political worldview. Without standing on a soapbox or giving speeches about its ideological sympathies, the film features a feminist hero, a character who fights against slavery, villainous politicians consumed by capitalistic drives, and an entitled rapist as the central baddie. Although critics such as Anton Bitel from the BFI describe The Dead Don’t Hurt as “transparently concerned” with modern political issues in their reviews, such ideas are regular fixtures in Western classics and not exclusively contemporary. Vivienne has the defiant independence of Joan Crawford in Johnny Guitar (1954); Holger joins countless Western heroes who have fought for the Union Army; the Mayor and Jeffries recall duplicitous, money-grubbing, and power-hungry town leaders in films such as Destry Rides Again (1939) and Unforgiven (1992); and black-clad, rapey villains such as Weston are a genre archetype. Mortensen adopts these familiar elements and redeploys them in a way that feels political because, well, audiences’ political antennae are more sensitive than ever, given the heightened culture war of recent years.

Mortensen’s direction adheres to the principle that form should serve the story and not call conspicuous attention to itself. There’s no flashy camerawork, just a deliberate aesthetic and mood that remains consistent for the 129-minute runtime. Even so, this is often a gorgeous film, drawing from actual locations in Durango, Mexico, and Canadian landscapes in Ontario and British Columbia. His musical compositions are lyrical and delicate, complimenting each scene and rarely announcing their presence, save for sharp aural pings when Holger, tracking Weston, finds a new clue on the trail to his target. Mortensen once again collaborates with cinematographer Marcel Zyskind, who shot the director’s first feature, Falling (2020), and before that, filmed Mortensen in the underrated thriller The Two Faces of January (2014). Mortensen and Zyskind might occasionally nod to John Ford. Still, they often create their own visual grammar that, like the narrative structure, has aspects of the film’s classical and revisionist inspirations. In particular, the film’s final shot is a stunner, capturing the coast in a luminous array of purple and blue Magic Hour light.

Mortensen’s direction adheres to the principle that form should serve the story and not call conspicuous attention to itself. There’s no flashy camerawork, just a deliberate aesthetic and mood that remains consistent for the 129-minute runtime. Even so, this is often a gorgeous film, drawing from actual locations in Durango, Mexico, and Canadian landscapes in Ontario and British Columbia. His musical compositions are lyrical and delicate, complimenting each scene and rarely announcing their presence, save for sharp aural pings when Holger, tracking Weston, finds a new clue on the trail to his target. Mortensen once again collaborates with cinematographer Marcel Zyskind, who shot the director’s first feature, Falling (2020), and before that, filmed Mortensen in the underrated thriller The Two Faces of January (2014). Mortensen and Zyskind might occasionally nod to John Ford. Still, they often create their own visual grammar that, like the narrative structure, has aspects of the film’s classical and revisionist inspirations. In particular, the film’s final shot is a stunner, capturing the coast in a luminous array of purple and blue Magic Hour light.

Along with its many admirable details, The Dead Don’t Hurt is another reminder that Vicky Krieps is among the finest screen performers working today. After Phantom Thread (2017) and Bergman Island (2021), she once again shows her range, taking what another film might define as a fallen woman and turning her into someone who a label cannot summarize. Many actors who become directors highlight their performers, and Mortensen’s screenplay gives Krieps intelligent, aching dialogue, from Vivienne’s words to Holger upon his return from battle (“How was your war?”) to her moving line to him later (“I just wanted a little tenderness”). But beyond Krieps, Mortensen’s writing and direction are generous to his entire cast, and he thankfully avoids giving the most significant role to himself. It’s an impressive achievement and work of genuine love, demonstrating what this second-time director has learned from working with some of the best filmmakers (Cronenberg, Peter Weir, Jane Campion, Ridley Scott, Peter Jackson, Brian De Palma, et al.), without ever feeling derivative or aping someone else’s style. Mortensen subverts expectations at every turn, even in the final confrontation between Olsen and Weston. An apparent lover of the genre, he imbues traditional Western themes with dimension and substance. This is a thoughtful, nuanced piece of filmmaking.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review