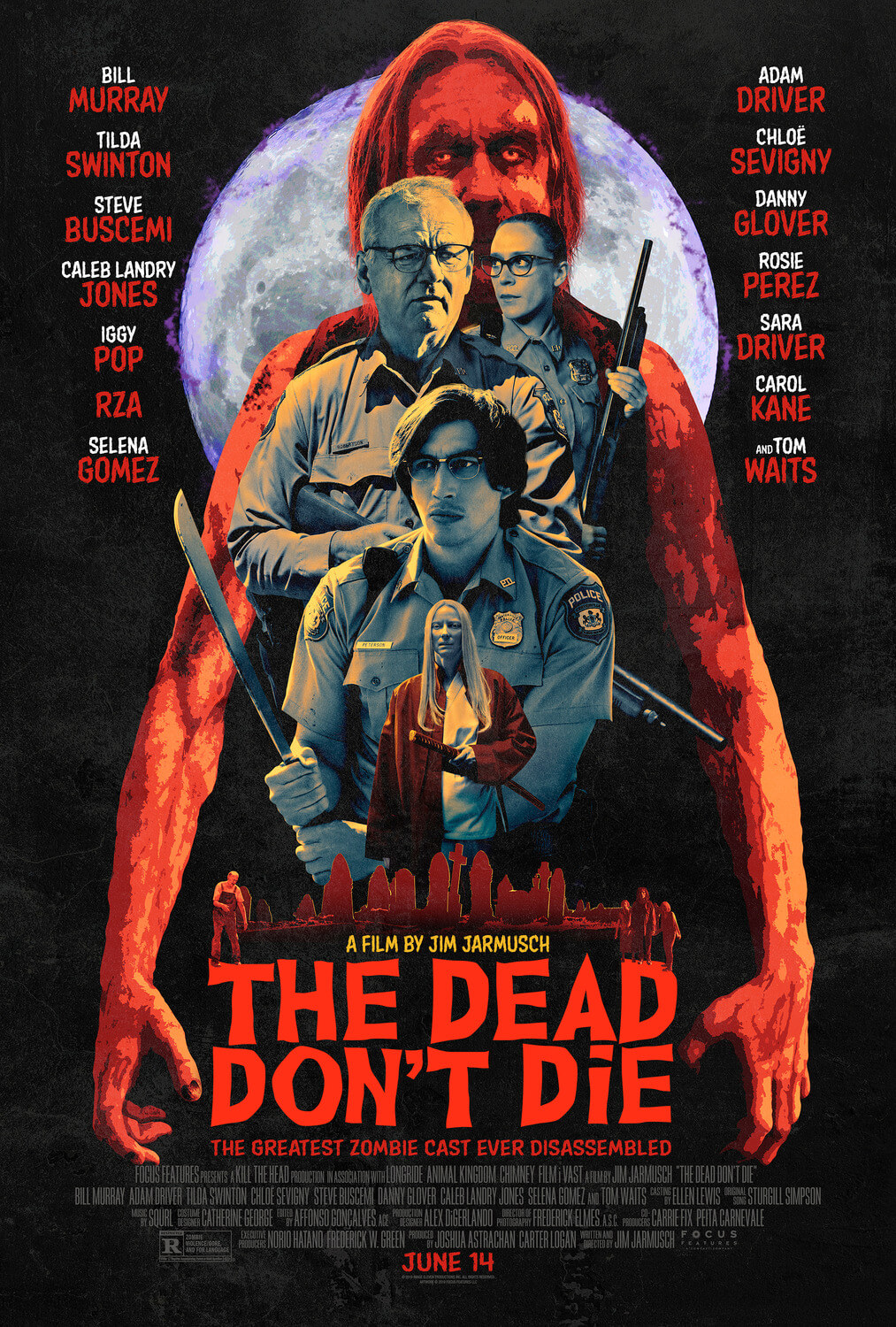

The Dead Don’t Die

By Brian Eggert |

In The Dead Don’t Die, Jim Jarmusch uses his unhurried style of arthouse filmmaking to characterize humanity’s continued sleepwalk through the apocalypse. Jarmusch ponders why no one acts as climate change heats the planet, kills the oceans, and melts the polar ice caps; as scientists predict that humanity has just a few decades left, unless we change our ways; as the digital age turns everyone into unthinking or reactionary clods; as fascism and intolerance return on a global scale; and as populist world leaders turn every country into an idiocracy. It’s all too much to process, resulting in a condition of zombie-like paralysis that has taken over our culture. Exhuming the spooky graveyard style of George A. Romero’s The Night of the Living Dead (1968), Jarmusch reflects on a world steering toward disaster, even though humanity greets the end with little more than a shrug and a snarky tweet about oblivion. Part genre experiment, part Jarmusch’s angry statement about the world today, The Dead Don’t Die uses the broad strokes of comedy and zombie horror to make sociopolitical observations. And while he doesn’t say anything new, the result is nonetheless charmed, frightening, and in the end, appropriately gloomy.

Jarmusch has experimented with genre since the mid-1990s, beginning with Dead Man (1995) his elegiac revisionist Western starring Johnny Depp, followed by Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999), a film extracted from the works of Jean-Pierre Melville and Akira Kurosawa, in which Forest Whitaker serves as a mob hitman who lives by the Bushido code. More recently in Only Lovers Left Alive (2013), he cast Tilda Swinton and Tom Hiddleston as vampire aesthetes who suck on blood popsicles and ruminate on their life of art appreciation. To whatever degree his approach on these films contains a knowing wink at the audience, his postmodernist perspective on The Dead Don’t Die extends the irony further, and the kick-a-dead-horse readability of his zombie metaphor becomes a commentary in itself. After all, everyone knows the world is coming to end; they’re just not doing anything about it. In the same vein, everyone in the film knows the zombie apocalypse means the end of humanity, but their deadpan reactions reveal a maddening cultural myopia—a quality in which everyone sees the end in sight but is too busy being indifferent or numbing themselves to get worked up about it.

The film opens among the moldy, timeworn gravestones of the local cemetery in Centerville, a sleepy hamlet with a population of 738. The town has been constructed in a consciously self-aware and figurative manner, as though Jarmusch wants you to know that he knows he’s being intentionally obvious. The hardware store is operated by a man named Hank (Danny Glover); local reporter Posie Juarez is played by Rosie Perez; and the town’s top lawman, Chief Cliff Robertson (Bill Murray), loves coffee and donuts. Along with Officer Ronnie Peterson (Adam Driver), the Chief scouts the forest by the cemetery for Hermit Bob (Tom Waits, under a bushy beard and mane), who lives off the grid and occasionally steals a chicken from Farmer Miller (Steve Buscemi, under a red “Make America White Again” cap). But the Chief and Ronnie notice things aren’t normal in their otherwise average town. Watches have stopped, television reception is fuzzy, the sun doesn’t set when it’s supposed to, and the incessant presence of the film’s acknowledged theme song, Sturgill Simpson’s “The Dead Don’t Die,” is all that plays on the radio.

“If you ask me,” says Ronnie in flat acceptance, “this is going to end badly.” It’s a statement that bothers the Chief in its certainty. “Stop saying that,” he orders. Only later, after the dead begin to rise from their graves and eat the citizens of Centerville, does Ronnie’s forecast seem oddly accurate. Some vague allusions—to the “polar fracking” that caused the Earth’s axis to change, giving the Moon a curious phosphorescent glow—hint that humans caused the outbreak of flesh-eating zombies. Self-interested media pundits, of course, assure that high-pressure drilling is not to blame. Even so, the Chief and Ronnie, joined at the station by the worrisome Officer Mindy (Chlöe Sevigny), prepare for the worst: “Zombies, ghouls, the undead,” warns Ronnie, convinced of his presence in a genre film—a notion about which the Chief remains incredulous. But an undead nightmare ensues, marked by cinematographer Frederick Elmes’ inky nighttime scenes and sauntering corpses that, when decapitated or shot, spill an embalmed black sand onto the ground below.

“If you ask me,” says Ronnie in flat acceptance, “this is going to end badly.” It’s a statement that bothers the Chief in its certainty. “Stop saying that,” he orders. Only later, after the dead begin to rise from their graves and eat the citizens of Centerville, does Ronnie’s forecast seem oddly accurate. Some vague allusions—to the “polar fracking” that caused the Earth’s axis to change, giving the Moon a curious phosphorescent glow—hint that humans caused the outbreak of flesh-eating zombies. Self-interested media pundits, of course, assure that high-pressure drilling is not to blame. Even so, the Chief and Ronnie, joined at the station by the worrisome Officer Mindy (Chlöe Sevigny), prepare for the worst: “Zombies, ghouls, the undead,” warns Ronnie, convinced of his presence in a genre film—a notion about which the Chief remains incredulous. But an undead nightmare ensues, marked by cinematographer Frederick Elmes’ inky nighttime scenes and sauntering corpses that, when decapitated or shot, spill an embalmed black sand onto the ground below.

Unfazed by the developments, Ronnie gives sound advice to his fellow officers: “You gotta kill the head.” But the film never resorts to a showpiece of bloody action scenes or thrills as another zombie film might. The closest it gets are scenes involving Zelda Winston (the last name an anagram for Swinton, who plays her), the local mortician with a Scottish accent and a penchant for samurai culture. She’s the sole oddball in the bunch—the clear standout in a small town comprised of familiar character types, and therefore she may as well be from another planet. When zombies attack, Zelda responds by cutting through the lot with her sword like Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo (1961). Aside from these moments, and a finale that ratchets tension out of the film’s dour fatalism, The Dead Don’t Die isn’t interested in a surface text. It uses what not so long ago was a cult genre, which has since gone mainstream and been homogenized by AMC’s The Walking Dead, to provide an accessible platform onto which it unleashes an acerbic critique of humanity today.

The tagline to Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) was “When there’s no more room in Hell, the dead will walk the Earth.” Jarmusch’s tagline should be, “When the Earth is doomed, the living will distract themselves.” Just as Romero used zombies to symbolize racism in America or rampant consumerism, Jarmusch uses the undead to show how coping mechanisms have replaced any need to engage with the world. The undead Iggy Pop groans for “coffee,” and the reanimated Carol Kane calls out for “Chardonnay,” while other brain-eaters remained hooked to their smartphones, and child-zombies moan for candy. All the while, the zombies destroy and eat living human flesh—their obsession with numbing themselves is only matched by the damage they do to other human beings. As for Ronnie, he’s already accepted their fate—Jarmusch showed him the script, so he’s resigned to the bitter end that awaits. To be sure, the self-referential streak running through The Dead Don’t Die punctuates the joke, suggesting that even if people had a script to the remainder of their lives, they would not change their self-destructive behavior.

The practical makeup effects used to render the zombie gore look nasty and palpable, but zombie fans hoping for a straightforward take on the genre should look elsewhere. Jarmusch has other things on his mind, and he’s ultra-aware of his pacing, references, and characterizations needed to achieve his message. Whereas the usual Jarmusch film could be called leisurely, he slows The Dead Don’t Die down to a zombie limp, setting every crawling scene to the guitar feedback sounds provided by Jarmusch’s band SQÜRL. He makes on-the-nose jokes, such as the right-wing Farmer Miller having a dog named “Rumsfeld,” not because the joke itself is funny, but because it’s the kind of joke that’s easy for his audience to digest. Jarmusch seems to say: Is this slow enough for your dulled mind to process? Is this joke obvious enough for you to laugh at? Have I made my commentary blatant enough for you? And while this could be seen as Jarmusch talking down to his audience, chances are the target audience can read the meta-ness of the joke. Everyone who doesn’t get it will see the film as nothing more than the moody sibling of Zombieland (2009), and they’ll be rolling in the aisles throughout.

The practical makeup effects used to render the zombie gore look nasty and palpable, but zombie fans hoping for a straightforward take on the genre should look elsewhere. Jarmusch has other things on his mind, and he’s ultra-aware of his pacing, references, and characterizations needed to achieve his message. Whereas the usual Jarmusch film could be called leisurely, he slows The Dead Don’t Die down to a zombie limp, setting every crawling scene to the guitar feedback sounds provided by Jarmusch’s band SQÜRL. He makes on-the-nose jokes, such as the right-wing Farmer Miller having a dog named “Rumsfeld,” not because the joke itself is funny, but because it’s the kind of joke that’s easy for his audience to digest. Jarmusch seems to say: Is this slow enough for your dulled mind to process? Is this joke obvious enough for you to laugh at? Have I made my commentary blatant enough for you? And while this could be seen as Jarmusch talking down to his audience, chances are the target audience can read the meta-ness of the joke. Everyone who doesn’t get it will see the film as nothing more than the moody sibling of Zombieland (2009), and they’ll be rolling in the aisles throughout.

But frankly, The Dead Don’t Die is more depressing than funny. Jarmusch’s cute references with a Samuel Fuller gravestone or the casting of Larry Fessenden leave a smile on your face for much of the runtime, but the responses to its humor are mostly inaudible; more prominent is the persistent feeling of dread and sarcastic anger emitting from the screen. When it’s all over, Jarmusch leaves us with two alternate philosophies, though the degree to which they are mutually exclusive remains in question. Earlier in the film, RZA appears as the delivery driver for “WU-PS” and offers some sage advice: “The world is perfect. Appreciate the details.” Is it any wonder that the idealistic character ends up a zombie? Nowhere in Jarmusch’s vision of the world are things perfect. Alternatively, Hermit Bob offers his own, decidedly more cynical observation as an endnote to the film, and his reflection seems to align with Jarmusch’s entire form-follows-function method of The Dead Don’t Die: “What a fucked up world.”

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review