The Dawn Patrol

By Brian Eggert |

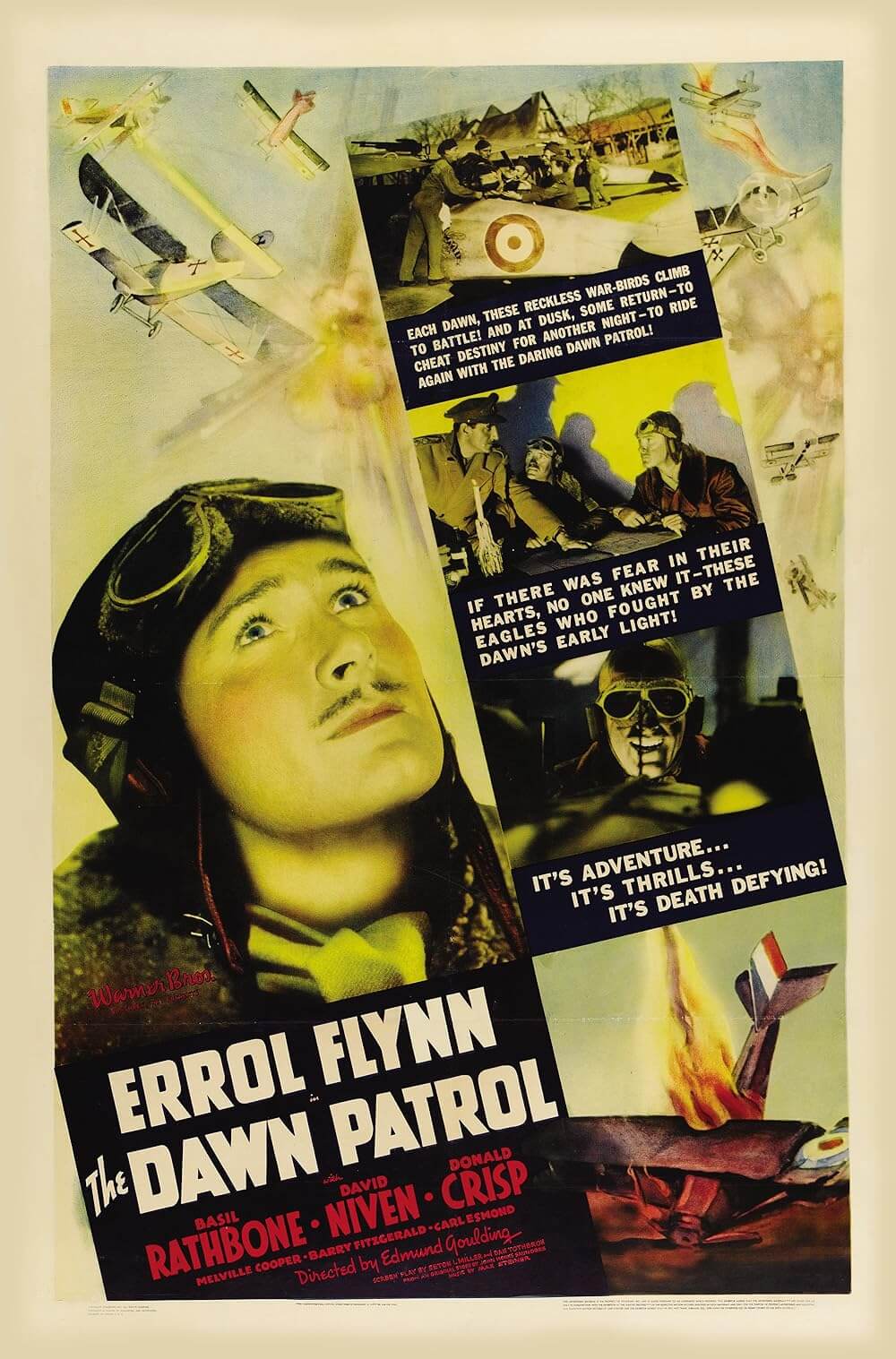

In 1930, legendary director Howard Hawks made an Oscar-winning film starring Douglas Fairbanks Jr. called The Dawn Patrol, based on a story by John Monk Saunders. Eight years later, Warner Bros. saw fit to remake the story with Edmund Goulding directing, but this time starring the sound era’s equivalent to Fairbanks Jr., Errol Flynn. Unlike his role in The Adventures of Robin Hood, Flynn wasn’t refreshing a character already made iconic by Fairbanks. Flynn plays Capt. Courtney, who Richard Barthelmess played in the original version; in the 1930 version, Fairbanks played the role of Lt. Scott, which in the ‘38 version, David Niven takes over. Even though the remake derives greatly from the original—some of the footage for the plane fight scenes was actually taken from the Hawks version—the ‘38 version outdoes its predecessor in every respect.

Capt. Brand (Basil Rathbone) runs the base for the 39th Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps, who in 1915 fought in and for allied France against the Germans. Brand sends out his pilots against impossible odds every day, following orders from his superiors as to how and where to attack the enemy. The orders aren’t always fair or realistic, but Brand’s top two pilots, Courtney and Scott, always make it back alive as they’re the most experienced aviators in the squadron. Each mission, Brand waits for the squadron to return and listens anxiously to how many planes pass overhead. Each time the number of returning planes diminishes until it’s always only Courtney and Scott coming back. Capt. Brand’s reinforcements are fresh-faced kids with little experience, most averaging ten hours of flight time. With every order he gives, Brand knows he’s sending these rookie pilots to their deaths, but there’s nothing he can do; he has to follow orders.

Flynn and Niven, real-life friends, give their characters a joyous attitude toward the war and do all they can to divert from the tragedy of their comrades’ deaths. The two gaily drink and sing “Hurrah for the next who dies,” filling the rec room with high spirits and gung-ho feelings. Carousing on drunken wine tours and up until all hours of the night, the incorrigible two are inseparable cads. Behind closed doors, their fury matches Brand’s for the unfair and unrealistic scheme of military intelligence. Daredevil pilots each, they also make Brand’s life a living hell by countermanding orders and taking unnecessary risks, jeopardizing the only two experienced pilots in the company. Against orders, Courtney and Scott daringly attack the enemy and take out an entire German airbase. As a result, Brand receives a promotion for his squadron’s victory and must choose his replacement. Brand selects Courtney, lividly acknowledging the irony attached to Courtney’s Captainship: finally, Courtney will know all the pains Brand had to endure. He will be forced to send men to their deaths and accept that there was nothing he could do about it. Eventually, Capt. Courtney receives a series of orders that may cause the death of his best friend, Scott.

The Dawn Patrol stands somewhere between an all-out anti-war statement and an actionized combat picture. This WWI story comes close to working as an anti-war film in that it preaches on the horrific and futile combination of violence and compliance to orders. If it weren’t for the action scenes, which draw the viewer into exciting dogfights and bomber warfare, the movie might actually detract from glorifying violence. As it is, the movie remains an oddly humanist action film where we delight in seeing Flynn and Niven blast down German planes, but we also realize the emotional conflict.

Edmund Goulding was best known for directing women; he worked with some of the best in Hollywood history. His position on the 1932 Best Picture Oscar winner Grand Hotel put Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford in his capable hands; in Dark Victory, he drew out one of Bette Davis’ greatest performances. Goulding might seem an unlikely choice for director of The Dawn Patrol given his filmography—there are no women in the cast, and it’s not typically his genre. But the director also briefly helped on Howard Hughes’ exemplary fighter plane epic Hell’s Angels, so the familiar territory allowed him to mesh war action with human drama in an expert fashion. Errol Flynn and David Niven both give capable performances in a film that’s comparable to the best of 1930’s war movies. Without going too deep into anti-war commentary or focusing too much on the action, The Dawn Patrol is pleasant entertainment—equally emotional and exciting.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review