The Dark Half

By Brian Eggert |

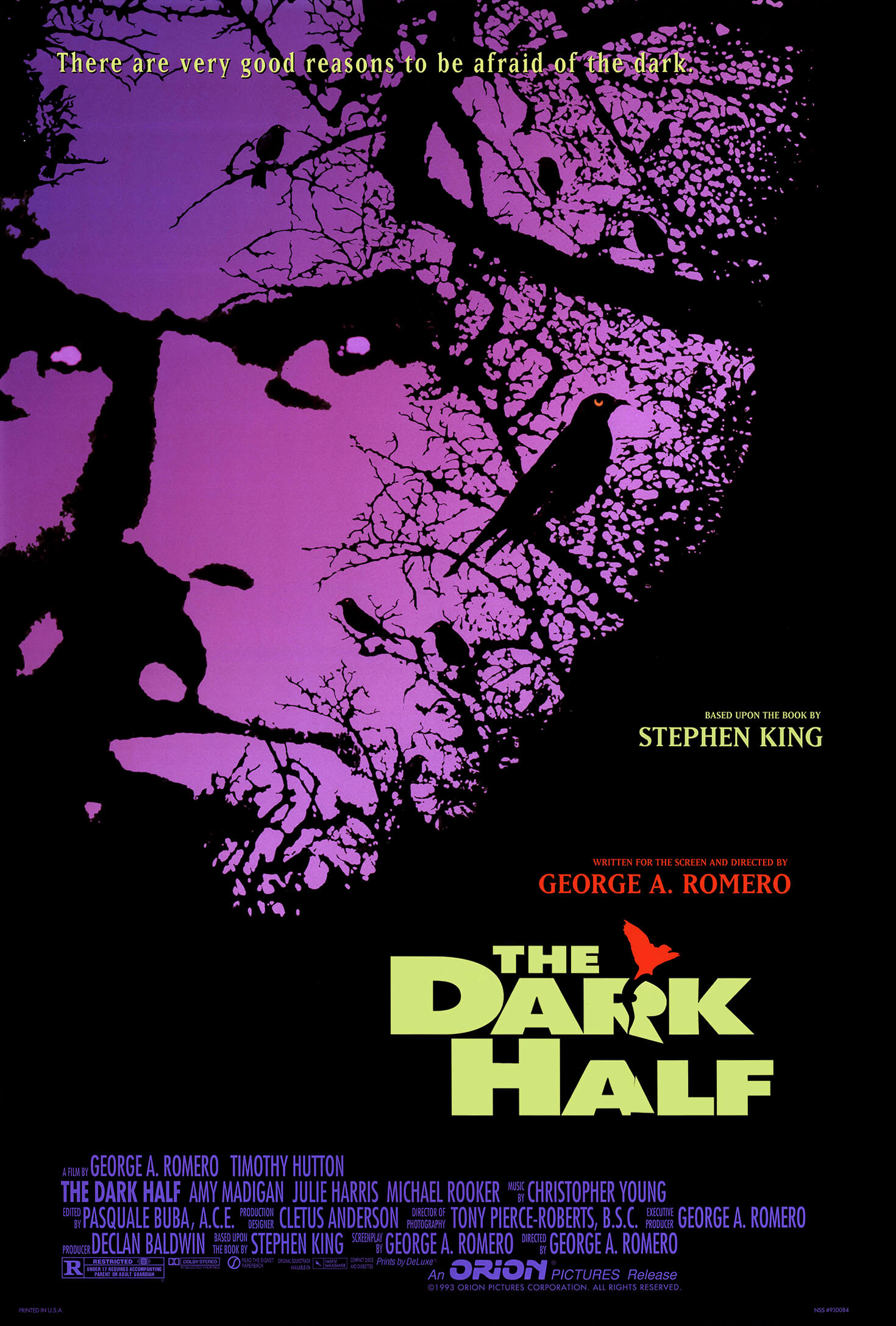

“The American way of death” is a phrase mentioned again and again in The Dark Half, George A. Romero’s film of the 1989 novel by Stephen King. The Maine-based author once described himself as the “literary equivalent of a Big Mac,” and you might ask yourself, what could be more American than that? Ever since his emergence in the 1970s, King’s work has introduced the macabre into pop-culture on a grand scale, proving that murder sells. In a way, King himself represents “The American way of death.” In Romero’s adaptation, the phrase refers to a publicity stunt. A respected author is ousted for using a pen name to write trashy pulp novels that sell better than his own yuppie fare. Rather than pay the blackmailer, he agrees to go public in the pages of People magazine. Why just own up to your sins when you can make a buck in the process? Now that’s the American way. His decision is a catalyst for a supernatural manifestation of the inner, darker side of his personality, which comes alive in the form of a murderous doppelgänger. Timothy Hutton plays both characters in the overlooked 1993 film, a work of rich imagery with roots in the American Gothic traditions of Edgar Allen Poe. Among the most faithful of all King adaptations, The Dark Half remains an underrated work in the cinema of both King and Romero.

King based his novel on the eight years he wrote under the pseudonym Richard Bachman. Beginning in 1977 with Rage, the author secretly released four books under the Bachman name through the publisher New American Library, including The Long Walk (1979), Roadwork (1981), and The Running Man (1982). Each of them had fewer pages, greater narrative economy, and downbeat endings next to the lengthy and comparatively more sentimental writing of King. The decision to write under an alternate name stemmed from King’s popularity, which had skyrocketed after his books Carrie, Salem’s Lot, and The Shining had become best-sellers in the 1970s. At that time, publishers were reluctant to distribute several books from an author in a single year, and the prolific King was writing them faster than his publisher was willing to distribute them. He resolved to write under a different name and keep the publicity of these books to a minimum, allowing them to sink or swim on their own merits. When King received a call asking what name should be attached to Rage, the author told The Washington Post in 1985 that he gave the name “Richard Bachman” because he had a book by Richard Stark (Donald E. Westlake’s pseudonym) on his desk and the band Bachman-Turner Overdrive on the radio.

Despite the occasional inquiry about the similarities between their work, King kept his identity as Bachman a secret, claiming the alter-ego was a chicken farmer from New Hampshire whose facial cancer had left him scarred, thus he shied away from giving interviews. The secret remained so until just after the publication of Thinner in 1985, when journalist Stephen Brown checked the copyrights with the Library of Congress and discovered they were registered to either King or his agent. Learning about Brown’s discovery, King called the journalist and agreed to an exclusive interview; he also allowed his publisher to circulate Thinner among booksellers as “Stephen King writing as Richard Bachman.” Although his secret was out and Bachman was ostensibly dead, King has playfully discovered the occasional “trunk novel” penned by the late Bachman over the years, including The Regulators in 1996 and Blaze in 2007. In the ensuing years, King must have lamented the pseudonym’s passing, as Bachman’s style had begun to develop a distinct personality. The Dark Half, which is dedicated to Bachman, seems to show King working through his feelings on the matter.

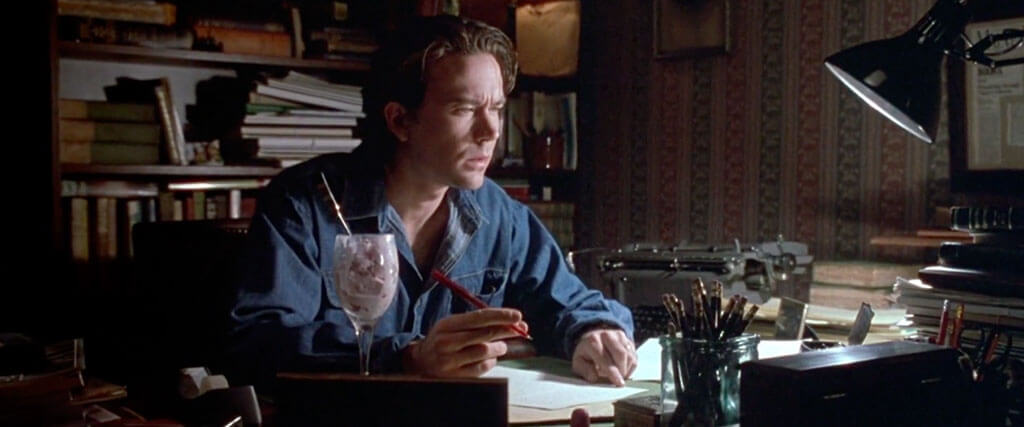

The film opens in a Gothic atmosphere. The young Thad Beaumont is a fledgling writer stricken by blackouts, seizures, and the phantom sounds of sparrows chirping in his head. When doctors attempt to remove the brain tumor believed to be the cause, they find the remnants of a mostly absorbed parasitic twin—a few teeth, some hair, and an eye that opens and looks around for the first time to see something other than the inside of a skull. As the surgeon prepares to remove the unwanted tissue, an enormous flock of sparrows surrounds the hospital, as if ushering the twin to its resting place. Already the story evokes Poe, with faint echoes of “William Wilson” in its use of the literary double and “The Raven” in its use of birds as a transmigratory device. Two decades later, Thad, played by Hutton, has become a creative writing professor. He lives a domesticated life; he’s married to Liz (Amy Madigan), and they have two infant children. Though, he can make ends meet because of his pseudonym, called “George Stark,” who authors a series of trashy best-sellers about a “high toned son of a bitch” named Alexis Machine. When Thad writes as Stark, his personality changes. He becomes another person: instead of his usual typewriter, he uses a Black Beauty pencil; he drinks too much; he turns mean.

The film opens in a Gothic atmosphere. The young Thad Beaumont is a fledgling writer stricken by blackouts, seizures, and the phantom sounds of sparrows chirping in his head. When doctors attempt to remove the brain tumor believed to be the cause, they find the remnants of a mostly absorbed parasitic twin—a few teeth, some hair, and an eye that opens and looks around for the first time to see something other than the inside of a skull. As the surgeon prepares to remove the unwanted tissue, an enormous flock of sparrows surrounds the hospital, as if ushering the twin to its resting place. Already the story evokes Poe, with faint echoes of “William Wilson” in its use of the literary double and “The Raven” in its use of birds as a transmigratory device. Two decades later, Thad, played by Hutton, has become a creative writing professor. He lives a domesticated life; he’s married to Liz (Amy Madigan), and they have two infant children. Though, he can make ends meet because of his pseudonym, called “George Stark,” who authors a series of trashy best-sellers about a “high toned son of a bitch” named Alexis Machine. When Thad writes as Stark, his personality changes. He becomes another person: instead of his usual typewriter, he uses a Black Beauty pencil; he drinks too much; he turns mean.

When an opportunistic sleazeball (Robert Joy) attempts to blackmail Thad to keep his pen name a secret, the author talks it over with his wife and makes the choice: kill George Stark with a publicity stunt, complete with magazine interviews, a mock funeral, and lots of winking photographs. What happens next isn’t quite clear, except for the fact that George Stark, a man who never existed, suddenly appears and proceeds to murder everyone involved in killing the idea of George Stark. It’s a colorful lot of victims, and one of the strengths of Romero’s screenplay is how well he uses King’s original dialogue to give even the smallest characters their personality: Photographer Homer Gamache dismisses all that pointless “folderol” of George Stark’s literary style. The cop who finds Gamache’s car, after Stark beats the chummy old man to death with his own wooden leg, remarks, “Ask mama if she believes this.” And of course, Stark’s drawl is a font of creepy, intimidating lines sourced from King’s novel that intentionally sound like a pulp fiction character. When the neighbor of a murder victim pokes his nose into a hallway and asks what’s going on out there, Stark replies with a tongue-in-cheek delivery, “Murder. You want some?”

Some credit for the distinctions between Thad Beaumont and George Stark belongs to the make-up department, which gave Hutton’s Stark a squarer jaw, a meatier brow, and a hairline that formed an angular widow’s peak. But Hutton and Romero formed many of the other differences, such as the director’s hint with “Are You Lonesome Tonight” by Elvis Presley on the soundtrack. First heard in the film when Thad was a boy in 1968, the song suggests that Elvis evidently had an impact on Thad’s subconscious. George Stark has grown into an Elvis Man with slicked-back hair, sideburns, and a penchant for black leather. He’s exactly the sort of rebel figure that a young repressed introvert would find appealing. Hutton plays Stark as rigid, confident, and intentional, whereas Thad is awkward and clumsy. Romero avoids calling too much attention to these traits; they’re up to the observer to discern. Despite its origins as an accessible King novel, The Dark Half has not been directed to hammy effect. His approach is elegant and restrained, especially compared to Romero’s dynamically edited zombie pictures. Consider a moment when Thad loses himself in a trance, one of many in the film where the gap between Thad and Stark seems to close in the realm of the mind. Romero doesn’t call out how much time has passed in this fugue state, aside from a cup of now-melted ice cream hidden in the shot.

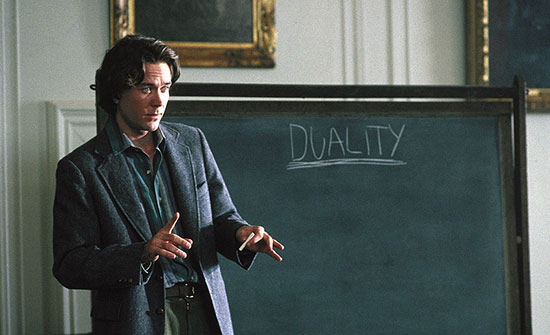

As Stark sets about using a straight razor on the throats of Thad’s associates, the material doles out one grisly murder after another. Thad becomes a prime suspect, investigated by Castle Rock’s Sheriff Alan Pangborn (Michael Rooker). But there’s more on King’s mind here than slasher folderol. A lecture in an early scene spells out the theme of duality, the inner and outer selves competing for attention in every writer. Watching the film, you can feel King’s anger and pain over losing Richard Bachman, a part of King’s personality that had begun to develop into a fully formed authorial voice. As Thad’s wise academic colleague (Julie Harris) explains, Stark is “an entity created by the force of your will.” The Dark Half acknowledges that human beings are complex and multifaceted, allowing for deviations in behavior that may seem uncharacteristic, which is an oddity in popular fiction, where accessible characters can usually be reduced to a few easily identifiable traits. Alas, in true King fashion, the supernatural finale finds Stark attempting to earn himself life by writing Thad out of existence. However, the film’s ubiquitous flocks of sparrows, the phantoms in Thad’s mind that also have a material existence as “psychopumps,” peck away at Stark in the last moments, carrying him away into the night.

As Stark sets about using a straight razor on the throats of Thad’s associates, the material doles out one grisly murder after another. Thad becomes a prime suspect, investigated by Castle Rock’s Sheriff Alan Pangborn (Michael Rooker). But there’s more on King’s mind here than slasher folderol. A lecture in an early scene spells out the theme of duality, the inner and outer selves competing for attention in every writer. Watching the film, you can feel King’s anger and pain over losing Richard Bachman, a part of King’s personality that had begun to develop into a fully formed authorial voice. As Thad’s wise academic colleague (Julie Harris) explains, Stark is “an entity created by the force of your will.” The Dark Half acknowledges that human beings are complex and multifaceted, allowing for deviations in behavior that may seem uncharacteristic, which is an oddity in popular fiction, where accessible characters can usually be reduced to a few easily identifiable traits. Alas, in true King fashion, the supernatural finale finds Stark attempting to earn himself life by writing Thad out of existence. However, the film’s ubiquitous flocks of sparrows, the phantoms in Thad’s mind that also have a material existence as “psychopumps,” peck away at Stark in the last moments, carrying him away into the night.

If the story’s lack of a central woman character represents a shift from Romero’s best work on Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Day of the Dead (1985), he still manages to emphasize and critique the pattern of violence among men in the film. Both Liz and, to a lesser extent, Pangborn’s wife (Chelsea Field), represent women in relationships with violent men. One night after being spooked by another Stark murder, Pangborn comes home and pulls a gun on his wife in the dark. Liz, meanwhile, has been developed into a thoughtful character, far from a mere stereotype, who concedes some measure of responsibility when she notes that Stark didn’t come into being “until we tried to kill him.” In this way, Romero avoids reducing King’s novel to a simple logline or a lean 90-minute gorefest; he allows the material to breathe for just over two hours, giving integrity to the domestic lives of both Thad and Pangborn. In fact, one of the few deviations from King’s novel is a scene Romero included where Liz reads a few pages from Thad’s new manuscript. With their two children on the floor next to her, the TV blaring cartoons, and Thad using an electric shaver in the next room, it’s a believable scene that brings the family to life. Another scene in the kitchen where Liz overcooks a turkey has the same quality. It is Romero’s attention to these small details that shows Romero’s care for the material.

Before making The Dark Half, Romero had circled several King novels—The Stand, Pet Sematary, and Salem’s Lot—for years prior to their first collaboration in 1982 with the horror anthology Creepshow, which was based on an original screenplay by King. Romero even purchased the rights to Pet Sematary before having to give them up to complete work on Monkey Shines (1988). With the exception of Tobe Hooper’s frightening television miniseries of Salem’s Lot from 1979, Romero probably would have made better versions of these eventual book-to-screen translations. But there was a stigma around Romero in the 1980s. His films had consistently failed to earn a sizeable profit, and he refused to conform to the commercially viable subset of 1980s horror defined by the slasher movies of the era. Rather than develop another winning franchise such as Friday the 13th or A Nightmare on Elm Street, Romero chose to invest himself in psychologically complex stories. With King’s novel The Dark Half, Romero recognized the Gothic tradition of the doppelgänger explored in the aforementioned Poe, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Double (1846), Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), among others.

The film would mark one of the director’s few major Hollywood studio productions. Usually a maverick working on the fringes with a small budget, Romero’s deal with Orion Pictures gave him $15 million to make the film but with omnipresent studio oversight. He was also working with an Oscar-winning actor as his leading man. Hutton took home the Best Supporting Actor statue for Ordinary People from 1980, and he continued to impress throughout the decade in collaborations with director Sidney Lumet on Daniel (1983) and Q & A (1990). Even so, Hutton caused tensions on Romero’s set by remaining in character at all times—not a problem on Thad Beaumont days, but potentially uncomfortable on George Stark days. The shoot took place in and around Romero’s hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, between late 1990 and early 1991. However, just before work was completed on the final sequence where sparrows reduce Stark to a bloody, screaming skeleton, production was shut down by the studio. Due to Orion’s mismanagement of its financials, the company that released Dances with Wolves (1990) and The Silence of the Lambs (1992), two winners of the Oscar for Best Picture, couldn’t afford to distribute their films. Orion filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. A year later, after Orion ironed out its financial problems, Romero and his team finished the final sequence with a combination of prosthetics and computer-animated birds. “They look like garbage,” Romero admitted in a later interview. He wasn’t wrong. The creatures in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) look better.

The film would mark one of the director’s few major Hollywood studio productions. Usually a maverick working on the fringes with a small budget, Romero’s deal with Orion Pictures gave him $15 million to make the film but with omnipresent studio oversight. He was also working with an Oscar-winning actor as his leading man. Hutton took home the Best Supporting Actor statue for Ordinary People from 1980, and he continued to impress throughout the decade in collaborations with director Sidney Lumet on Daniel (1983) and Q & A (1990). Even so, Hutton caused tensions on Romero’s set by remaining in character at all times—not a problem on Thad Beaumont days, but potentially uncomfortable on George Stark days. The shoot took place in and around Romero’s hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, between late 1990 and early 1991. However, just before work was completed on the final sequence where sparrows reduce Stark to a bloody, screaming skeleton, production was shut down by the studio. Due to Orion’s mismanagement of its financials, the company that released Dances with Wolves (1990) and The Silence of the Lambs (1992), two winners of the Oscar for Best Picture, couldn’t afford to distribute their films. Orion filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. A year later, after Orion ironed out its financial problems, Romero and his team finished the final sequence with a combination of prosthetics and computer-animated birds. “They look like garbage,” Romero admitted in a later interview. He wasn’t wrong. The creatures in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) look better.

The Dark Half and several other Orion films slotted for release in 1991 and 1992 were pushed back until 1993 and later. When it was eventually released, Romero’s film didn’t fare well with either critics or audiences, most of whom were then accustomed to the poor quality of most King adaptations. The majority of reviews cited Hutton’s performance as the highpoint, while the underexplained supernatural elements took the blame as the film’s low point. Roger Ebert complained that the film fails to explore the “preternatural opening theme” of twins by not revealing more about George Stark. But Ebert overlooks that most literary doubles have no origin story; they appear as if from fog to reflect the protagonist. Others wanted something more terrifying than supernatural and psychological. In Entertainment Weekly, Owen Gleiberman quipped, “The most frightening thing about this movie is that King and Romero actually thought it was scary.” Vincent Canby at The New York Times was among the few to praise the film, remarking that it “outdistances every other King adaptation I’ve seen” besides The Shining. At the U.S. box-office, the film earned back just $10 million of its $15 million budget, likely due to unenthusiastic reviews and fatigue from disappointing King adaptations. And while the film’s performance may not have curbed Hollywood’s enthusiasm about King’s brand name, it certainly marked a turning point in Romero’s career. After The Dark Half, the famed director experienced a seven-year gap in his output, the longest period in his filmography without work to that point.

Even today, The Dark Half has not been widely reassessed as an unjustifiably forgotten work by Stephen King and George A. Romero. But if nothing else, the film is some kind of marker, as it’s rare to find two monuments of the horror genre attached to a single project. Moreover, Romero has done an uncommon thing by remaining close to King’s text. Usually, when filmmakers do this, the result translates to ungainly and awkward cinema that fails to capture the psychological underpinnings of King’s characters. Perhaps this was inevitable given that Thad Beaumont’s mental state becomes a physical character in the story, and therefore, the film could not help but bring his interior world into an exterior space. Romero embraces the Gothic nature of the story, supported by cinematographer Tony Pierce-Roberts’ use of New England’s overcast skies to create a mysterious, chimeric mood. Whether its a quality of King’s writing on this particular book or Romero’s exceptional skill at adapting it, The Dark Half balances psychological, phantasmic, and visceral horror. Grounded by Hutton’s two committed performances, Romero has made the rare King adaptation that gets to the center of the characters as they existed on the page, and it works remarkably well.

Sources:

Gagne, Paul. The Zombies that Ate Pittsburgh. Dodd, Mead & Company, 1987.

Williams, Tony. The Cinema of George A. Romero: Knight of the Living Dead. Second Edition. Wallflower Press, 2015.

Williams, Tony, editor. George A. Romero: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review