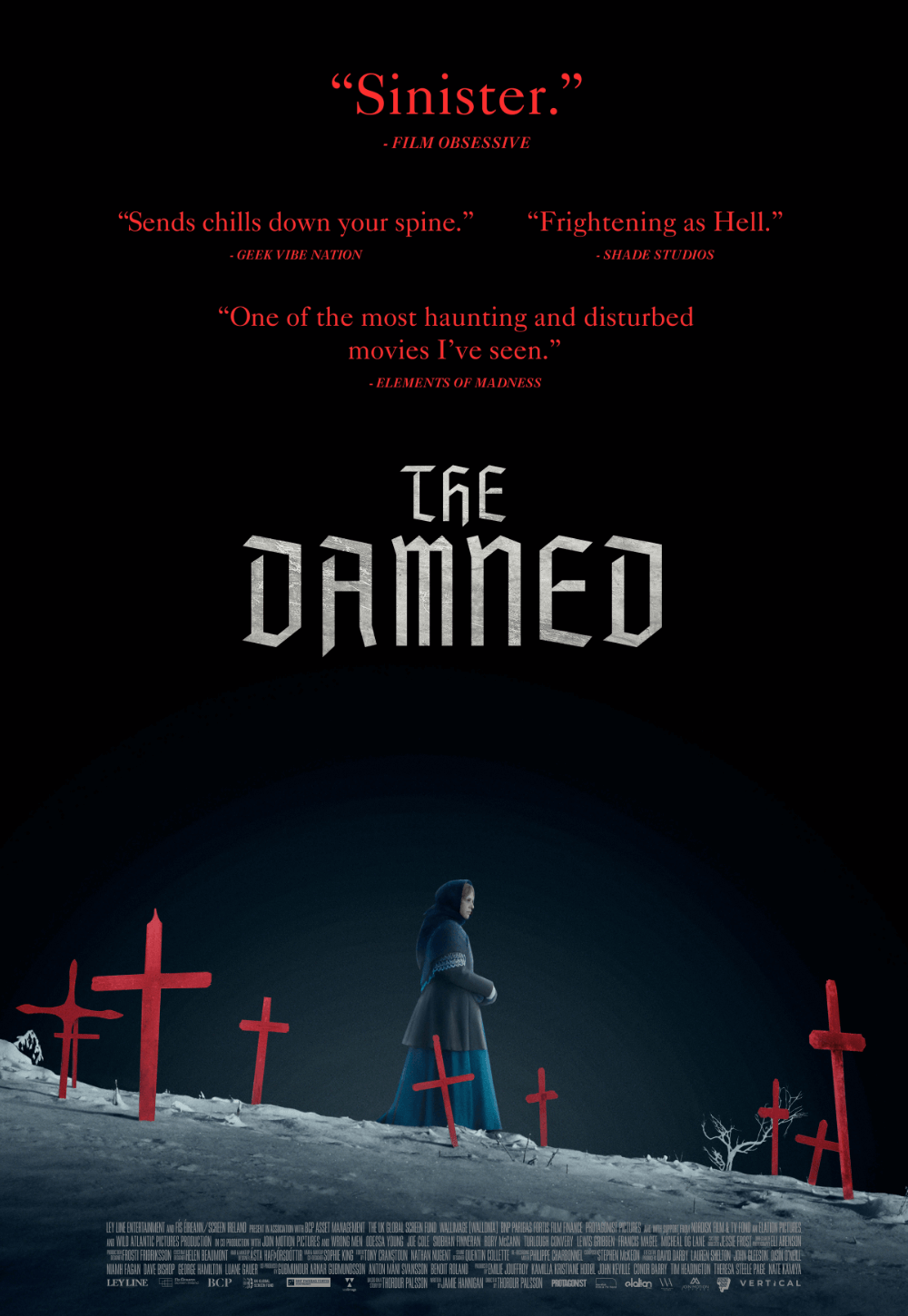

The Damned

By Brian Eggert |

A tense morality play about guilt set during an unforgiving winter descends into an undercooked alternative to John Carpenter’s The Fog (1980) in Thordur Palsson’s The Damned. Unfolding in a small, isolated fishing outpost in the nineteenth century, the production benefits from genuine Icelandic location photography. But most of these details of time and place must be gleaned by the attentive viewer. Refreshingly, the film doesn’t reveal its location or period with titles or expositional dialogue. Its characters inhabit an allegorical cautionary tale against xenophobia, anchored in a heavy dose of Christian guilt over not welcoming strangers (see Hebrews 13:2: “Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for by so doing some people have shown hospitality to angels without knowing it”). In our increasingly isolationist world, the theme resonates, but that doesn’t mean The Damned does.

Odessa Young stars as Eva, a young widow who inherited her husband’s fishing outpost and boat after his death. Though surrounded by brutal conditions and stranded by a harsh winter, Eva and the fishermen at her station recognize this is a “place of opportunity.” They need only survive the coming months with careful food rationing. Everyone’s concerned about the winter; however, it’s nothing a few fishing songs cannot cure. But then the crew spots a large boat sinking a few hundred yards offshore, and they debate whether to assist. The chief helmsman, Ragnar (Rory McCann), refuses to brave treacherous waters to help “strangers” or “foreigners.” Reluctantly, Eva agrees that the risks are too great. That doesn’t stop them from indulging in a drum of meat from the boat that washes ashore or heading out to find more of the sunken ship’s goods that might still be floating on the surface.

What they find is several survivors from the ship, whom Eva and company refuse to help because there are too many to help without risking their well-being. After a disastrous encounter, Eva is overcome with guilt, fueled by Helga (Siobhan Finneran), who spins a yarn about draugar—the hateful, zombielike specters of the dead sailors who return to haunt the living and turn them against each other. This leads to phantom images, jump scares, creepy nursery rhymes, and other familiar supernatural tropes. Predictably, Eva develops a romance with one of the fishermen (Joe Cole) when he shows her how to use a rifle, and their proximity leads to a banal moment of sexual tension. Palsson directs such moments with immersive patience, allowing Stephen McKeon’s atmospheric score to set a dread-laden tone. But it’s all so familiar and lifeless that one is hard-pressed to care.

Born in Iceland but educated at the UK’s National Film and Television School, Palsson has spent his career thus far telling Icelandic stories. His series The Valhalla Murders debuted on Netflix in 2020, and The Damned marks his feature film debut. The director uses the harsh backdrop well, conveying the spare surroundings and oppressive cold with realism. There’s an austere beauty to the setting as well, reflected in the jagged hills and overcast skies surrounding the camp. Eli Arenson’s cinematography showcases the environment, using natural light outside and oil lamps for interior scenes. Technically, The Damned is an assured and well-assembled picture, boasting another strong performance from Young (see also Shirley and Mothering Sunday). But where it’s lacking is a desperate yearning to be poignant and thematically resonant, so much so that it forgets to be scary or emotionally engaging.

While the draugar look creepy and vaguely resemble the waterlogged lepers from The Fog, Palsson too often deploys them for repetitive shocks, accented by a loud boom. These devices might have been more effective had Palsson gone for a pulpier exploration of these same themes as Carpenter did. Instead, screenwriter Jamie Hannigan finds only dour, humorless, and ultimately unconvincing ways to show how guilt overwhelms these characters, leading to accusations, paranoia, and death. Neither the supernatural threat nor the psychological one amounts to much beyond a severe mood, and the movie’s use of its 89-minute runtime doesn’t allow for much depth or mystery, evidenced by the over-articulated finale. Palsson shows himself capable of delivering a formally sound feature, but the writing feels underdeveloped.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review