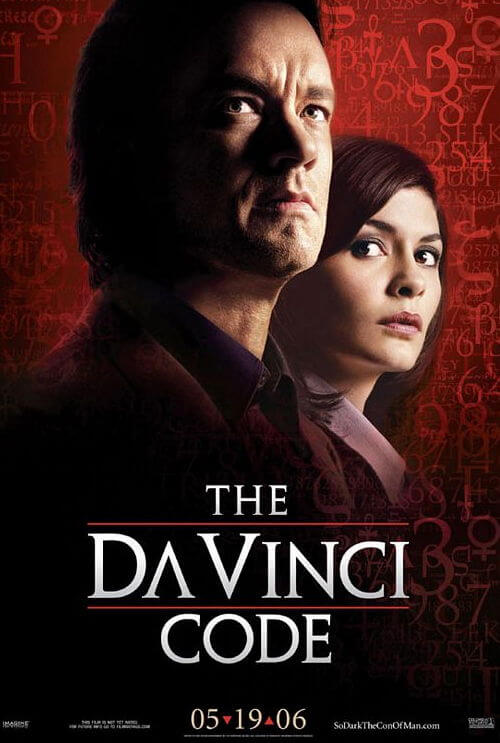

The Da Vinci Code

By Brian Eggert |

The Da Vinci Code is a movie about ideas. And those ideas are very clever, at once intriguing and controversial enough to send audiences racing into their local library, or at least Wikipedia, to find out the real story. Unfortunately, the movie’s ideas mask any semblance of character development or believable narrative, as the ideas don’t have the time or room to allow for such things within the script—they’re too busy being fascinating. Dan Brown’s novel sold some 60 million copies because its breakneck pace and audacious ideas were easily accessible in a familiar formula for pulpy fiction. And with the amount of discussion generated by the book, its author’s merely so-so writing abilities were conveniently overlooked by readers. Nevertheless, the discussion remained, and books were sold in some 40 languages. And so, Hollywood couldn’t resist making the movie from a novel everyone read and thus knew the twist ending to. However meaningless this decision might’ve been, the result couldn’t be more disappointing.

Attempting to be a high-brow thriller, like Indiana Jones except without an ounce of humor, The Da Vinci Code comes from ultra-bland director Ron Howard, whose career is one of the all-time most overrated filmographies in cinema. Screenwriter Akiva Goldsmith tackles Brown’s material, though his previous output on Batman & Robin and Lost in Space suggests he should never be allowed near a computer or typewriter ever again. They signed lovable everyman Tom Hanks to star in a personality-less performance, despite personality being exactly what Hanks is known for. And along with the picturesque locales from Brown’s text, which have a beauty that is almost completely disregarded by Howard, we have a film that misses almost every opportunity to become the sure thing it should’ve been.

Professor of Symbology Robert Langdon (Hanks) is called to the Louvre, where colleague Jacques Saunière (Jean-Pierre Marielle) was murdered by gunshot. But before he died, Saunière left a series of clues to finding his killer. As the title suggests, these clues are hidden among the museum’s various works by Renaissance painter Leonardo Da Vinci, including the way Saunière’s corpse resembles the position of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Hard-headed police investigator Fache (Jean Reno) suspects Langdon is involved. Still, Saunière’s granddaughter and police cryptographer Sophie Neveu (Audrey Tatou) trusts Langdon and helps him uncover both the mystery of Saunière’s murderer and one of history’s great covered-ups by the Catholic church.

The movie progresses through a series of exotic and historic venues where more clues are revealed, but then Langdon and Neveu are pursued, so they flee to the next backdrop and the next clue. On their tail are Fache and creepy albino Opus Dei zealot Silas (Paul Bettany), both taking orders from misguided Bishop Manuel Aringarosa (Alfred Molina). In need of help, our heroes visit Anglophile historian Sir Leigh Teabing (Sir Ian McKellen), who informs them of what they’re really looking for. McKellen steals the show in his supporting performance, both lively and clever, with more personality in his little finger than both Hanks and Tatou portray combined.

Much has been made of the story’s big reveal, which suggests that Mary Magdalene and Jesus Christ conceived a child, and the bloodline continues to this day, its heir kept secret by the Priory of Sion and continually hunted by Opus Dei—religious factions exaggerated and skewed by Dan Brown’s text, as if that matters. Liberties with history are taken, and some readers are particularly offended by this, accusing Brown and, later, the filmmakers of promoting religious heresy and historical inaccuracy. Though anytime anyone says anything contradicting Christian tenets or those of any other religion, they’re bound to be met with some strong reactions—that’s the nature of blind faith.

What those fanatical critics forget is that Brown’s book was sold in the fiction section of your local bookstore, and Howard’s movie is in the thriller genre. It’s not non-fiction, not a documentary. This is a fact-finding mystery told with all the trappings the genre offers, simply with a religious-themed hook, like Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. American historians didn’t balk at the absurdity of National Treasure when Nicolas Cage was finding secret maps on the back of the Declaration of Independence. Why is this any different? Because the central McGuffin is Christ’s long-lost bloodline. Had Brown made wild, thinly researched claims about some non-Christian subject, no one would have complained about historical or religious accuracy.

The book and movie take admitted liberties with history, but they also have some truth to them. Yet, because they demand that the audience question doctrine, ardent religious followers are upset because heaven forbid anyone questions their dogma, which serves as a hearty commentary on the fragility of religious belief. Whoever thought seeking knowledge by asking questions could be so dangerous? Then again, the Catholic Church’s history of atrocities toward people who ask the wrong questions is well documented. So the events in this fiction are rendered possible, if implausible, by association.

The bottom line is that The Da Vinci Code, for all the books and movie tickets it sold (the film earned some $217 million in United States ticket sales alone), still does not surpass the limitations of being an uninvolving thriller. Howard’s direction doesn’t have the personality, and Goldsmith’s writing doesn’t have the punch to enliven this story with fleshed-out characters. Instead, the two-and-a-half-hour runtime is spent chasing an idea, which, once revealed, really isn’t confirmed at all. The filmmakers were so concerned about doing justice to the book’s ideas that they forgot there’s an audience to entertain.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review