The Creator

By Brian Eggert |

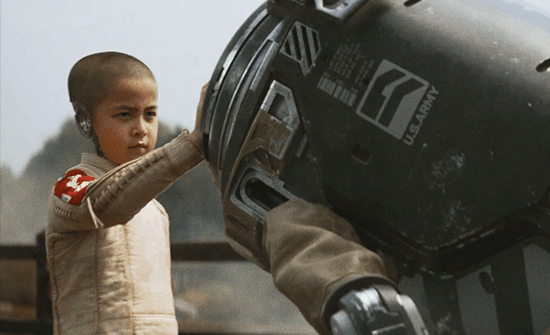

In The Creator, the year is 2065, and people have built massive structures that reach beyond today’s skyscrapers, travel by hovering motorcycles and cars, and take shuttles to the moon. Humanity has also created artificial intelligence robots, which, when regarded head-on, appear indistinguishable from people. Some serve as police officers and factory workers; they even have emotions. Despite the advances in technology in these futuristic surroundings, when Joshua, the hero played by John David Washington, discovers that an unprecedented “simulant” child—the resident Chosen One played by Madeleine Yuna Voyles—can turn off a television with her super-computer brain, he’s amazed. He has never seen anything like it. Yet, any viewer with a smart TV and a virtual assistant like Alexa or Siri knows it’s no big deal for modern-day technology to turn on/shut off an appliance with a simple voice command. To be sure, The Creator doesn’t boast many bright ideas; most of them, it borrows from better films about artificial intelligence and what it means to be human. Even so, the production boasts a visual luster and scope that renders even its most thematically banal scenes into stunning set pieces.

The product of director Gareth Edwards, who co-wrote the screenplay with Chris Weitz (About a Boy, 2002), The Creator looks and feels like a Star Wars movie by another name. Fitting, since Edwards helmed Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016). For instance, the police bots look suspiciously like Lucas-brand droids, and the visual compositions by the two credited cinematographers (Greig Fraser, Oren Soffer) evoke those fateful magic hour shots on Tatooine, where Luke Skywalker considers fulfilling his destiny. But rather than another variation on Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, Edwards concocts a predictable story where AI becomes “more human than human” and supposedly attacks Los Angeles with a nuclear weapon. The United States responds by waging war on their robotic counterparts, which take refuge in the more AI-sympathetic Republic of New Asia. Edwards draws from Vietnam War footage and the US’s invasion of Iraq after 9/11 to evoke a parable for unnecessary overseas conflicts, the dehumanization of political enemies, and the collateral damage of imperialistic world policing.

Although science fiction can and has been used to allegorize complex sociopolitical issues before, The Creator feels akin to Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium (2013), rendering its message in blatant, uncomplicated terms. The obvious plotting follows Joshua, an undercover Army operative assigned to locate the mysterious Nirmata, the inventor of advanced AI. But during his mission, Joshua falls in love with and marries the AI-friendly Maya (Gemma Chan), who becomes pregnant and, after realizing her husband is a traitor to her cause, is tragically killed during a military raid. Five years later, Joshua no longer considers himself part of the Army. Regardless, a commander named Howell (Allison Janney, in Stephen Lang mode) enlists Joshua to locate a top-secret AI “superweapon” called Alpha O, promising him that Maya is alive and well. When Joshua learns that the so-called superweapon is an AI child, nicknamed Alphie, who has a special connection with Maya, his loyalties change. The new mission becomes destroying the US’s version of a Death Star, a vast AI-hunting ship called Nomad.

Following a similar trend with his previous work on Monsters (2010), Godzilla (2014), and Rogue One, Edwards shoots in real-life locations and integrates special effects into each shot. However obvious a solution this may seem, it’s not always the Hollywood standard. Many studio productions with The Creator’s scope shoot almost entirely on green screen soundstages, where every detail is rendered with computers in post-production, using AI no less. A self-taught effects animator accustomed to stretching his budget, Edwards knows how to make his production’s reported $80 million budget look like it cost double that. Whereas the effects in most superhero and sci-fi movies today range from mildly unconvincing to downright cartoonish, Edwards finds a balance between his lyrical camerawork, atmospheric landscapes, and the futuristic milieu. The effects used to depict the robots, whether they look like droids or humans, are always impressive. Other choices feel less harmonious, such as the few needle drops of primarily twentieth-century music (Has no new music been developed in 65 years?).

Following a similar trend with his previous work on Monsters (2010), Godzilla (2014), and Rogue One, Edwards shoots in real-life locations and integrates special effects into each shot. However obvious a solution this may seem, it’s not always the Hollywood standard. Many studio productions with The Creator’s scope shoot almost entirely on green screen soundstages, where every detail is rendered with computers in post-production, using AI no less. A self-taught effects animator accustomed to stretching his budget, Edwards knows how to make his production’s reported $80 million budget look like it cost double that. Whereas the effects in most superhero and sci-fi movies today range from mildly unconvincing to downright cartoonish, Edwards finds a balance between his lyrical camerawork, atmospheric landscapes, and the futuristic milieu. The effects used to depict the robots, whether they look like droids or humans, are always impressive. Other choices feel less harmonious, such as the few needle drops of primarily twentieth-century music (Has no new music been developed in 65 years?).

Most of The Creator consists of Joshua and Alphie navigating the New Asia underground, only to be discovered by the US military personnel or AI cops, prompting them to run again. Along the way, Joshua survives the shockwaves of two missiles and one suicide-robot attack, straining even the credibility of this sci-fi world. The repetitive plot deploys a chapter structure, with titles such as “The Child” or “The Mother,” designed to give the material grandiosity. But it’s one laser-gun battle after another, with some soulful, faux-Malickian flashbacks of Joshua and Maya’s relationship inserted between action sequences, supposedly building a character dynamic. However, if Washington’s career since breaking out with the terrific BlackKklansman (2018) is any indication, he lacks his father’s range, making the central relationship feel surface level. Like his roles in Tenet (2020) and Malcolm & Marie (2021), Washington has one dimension here, maybe two. For her part, Voyles makes Alphie immediately sympathetic, mainly because Edwards has written her as a beacon of innocence, using her ability to cry and read schmaltzy dialogue (“Where is Heaven?” becomes her version of the T-800’s “Why do you cry?”) to bolster tear-jerking scenes.

If any of this sounds familiar, you’re probably thinking of James Cameron’s Terminator movies, with a hint of his more apropos Vietnam parallel, the jingoistic Aliens (1985). When one of Joshua’s fellow soldiers drives a personalized tank with robot arms, it recalls the Power Loader, the yellow machine driven by Sigourney Weaver at the end of that film. Questions essential to the genre, about whether AI is “just programming” or actual life, receive only a superficial investigation. Those typical themes, better questioned in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)—clear influences here—remain secondary to framing AI as a parallel for Americans treating various cultures, especially Asian cultures, as Others. But given the warning signs from scientists and developers about the dangers of AI in recent years, not to mention the combative presence of AI in Hollywood today, Edwards’ sunny portrait of AI as a natural evolution of humanity seems chillingly optimistic about the prospect of it representing the future of humanity.

Although the buzz about The Creator is that it’s an original sci-fi movie not based on previously established intellectual property—a rarity these days—Edwards and Weitz haven’t concocted anything so novel. They follow a playbook of winning sci-fi scenarios so closely that the result feels conceived by AI (perhaps a screenwriting program that couldn’t resist working a pro-AI message into the narrative). The story isn’t particularly challenging either. Consider how Spielberg tests the viewer’s affection for his robot boy in A.I. Artificial Intelligence, with scenes where his inhumanity leads to uneasiness. There’s nothing so off-putting about Alphie, a character whose humanity is never questioned after her first appearance watching cartoons. The Creator goes down smoothly, never deviating from its predictable path, never surprising or provoking its audience. However, science fiction should confront viewers with philosophical and moral questions. Instead, Edwards has molded his story to commercial specifications, but fortunately, it’s so well put together as visual entertainment that its escapist qualities almost outweigh its absence of new ideas.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review