The Commuter

By Brian Eggert |

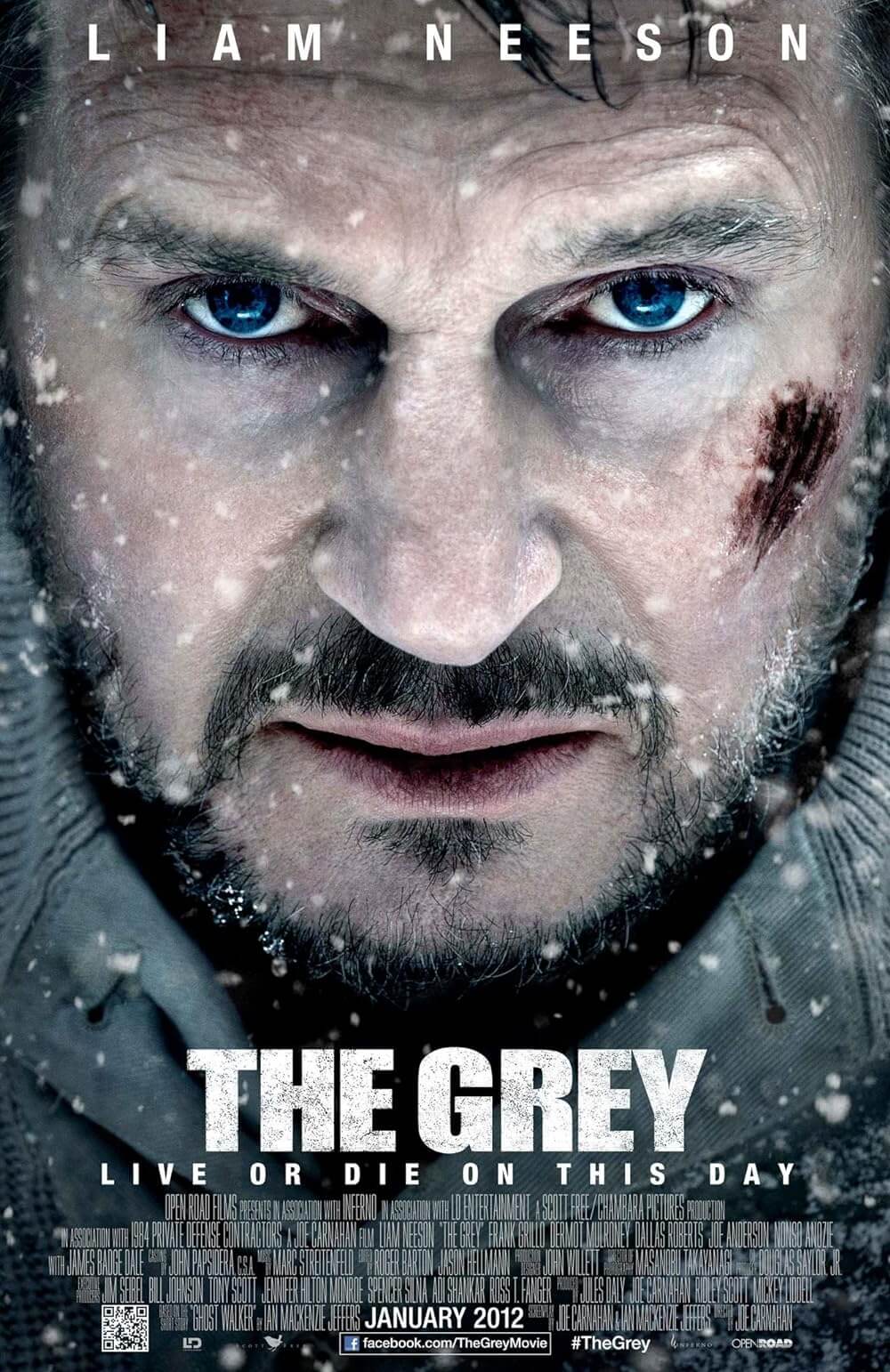

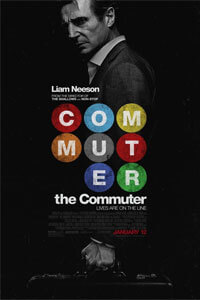

In each of Jaume Collet-Serra’s four collaborations with Liam Neeson, including their latest, The Commuter, the director takes an excellent, decidedly Hitchcockian thriller concept and squanders the setup’s potential on sloppy writing and poor execution. There was Unknown (2011), where Neeson wakes up after a car wreck to discover his wife doesn’t recognize him, someone has stolen his life, and he’s the victim of an absurd conspiracy. Non-Stop (2014) featured Neeson as an Air Marshal trying to solve a whodunit on a commercial flight, only to discover that he’s been framed for murder. Playing a former hitman in Run All Night (2015), Neeson tries to protect his son from gangsters and crooked cops over the course of one frantic evening. Each of these titles relied on the commercial prospects of Liam Neeson: Action Hero. The filmmakers ignored that their scripts needed serious rewriting because, after all, the concept was marketable and the opening weekend box-office would be enough to turn a profit.

The Commuter is no different, in that the story (penned by Byron Willinger, Philip de Blasi, and Ryan Engle) has a worthy hook, but it follows through with a series of dull Screenwriting 101 choices. Neeson plays Michael MacCauley, a former cop devoted to his wife (Elizabeth McGovern) and son (Dean-Charles Chapman). Every day, MacCauley takes a commuter train from his upstate suburban home to New York City, where he’s sold insurance for the last ten years. One day on his routine trip home, he’s approached by a talkative, mysterious woman (Vera Farmiga) who offers him $25,000 in cash now, and another $75,000 afterward, if he locates a passenger riding on the train. The reasons why, she says, are unimportant, but the money is real. Normally such a proposition would raise alarm bells, but just that morning, MacCauley lost his job and—being 60-years-old, hoping to retire soon, and his son going away to college—he needs the money. After Farmiga’s character all but evaporates, he plays along in what seems like a harmless game. Of course, the game proves deadly, and when MacCauley attempts to contact his former partner (Patrick Wilson) for help, Farmiga demonstrates that she’s watching his every move.

And so, MacCauley relies on his particular set of skills to maneuver the situation, requiring him to identify, from the handful of non-regular passengers on the train, which one “doesn’t belong.” Each passenger not recognized from MacCauley’s usual commute becomes a suspect. Taking a cue from Speed (1994), the passengers in question are a diverse assortment of cliché character tropes: there’s a brash, fast-talking stockbroker (Shazad Latif); a chummy old-timer (Jonathan Banks); a no-nonsense nurse (Clara Lago); a rebellious teenage misfit (Florence Pugh); an Eastern European roughneck (Roland Møller); and plenty others. MacCauley also has a tight deadline—he must locate the passenger before the last stop; otherwise, his family will suffer the consequences. After a few underwhelming fistfights (all of which MacCauley loses, strangely enough) and some CGI-enhanced excursions on the train’s exterior (as it turns out, Hollywood hasn’t made high-speed train climbing look any more plausible since Mission: Impossible in 1996), MacCauley remains no closer to finding his target.

The writers take the tired Chekhov’s gun principle—the notion that every story element must have a significant purpose—to heart. Every moment in the film, from the opening credits sequence onward, serves the plot. Some might call this “tightly constructed” writing or a “taut” approach, but the viewer can see the screenwriters pulling strings. Consider how MacCauley stops for a drink after being laid off. He takes note of a news broadcast in which a witness for a high-profile corruption case has been killed. Because every newly introduced piece of information in the script has a correlating purpose later in the story, we just know this witness’ death will prove important. Just as we know the villain of the story is probably someone established early on—most likely one of the more recognizable faces in the cast. The conspicuous presence of Wilson and Sam Neill could provide some answers. Indeed, the ham-fisted storytelling here is predictable, laughably so, removing any hope for mindless thrills, despite the script having some twists and turns.

Collet-Serra engages in his usual, distractingly showy camerawork; although, here the root word “camera” remains suspect. Much of The Commuter appears to be a CGI creation. Every landscape outside of the train window is achieved digitally, while most exterior shots of the train racing through a station look like a videogame cutscene, lending an artificial and distancing layer to everything before us. A similar problem hampered last year’s Murder on the Orient Express remake. Moreover, editor Nicolas De Toth chops the exciting scenes into unrecognizable, microsecond bits, eliminating any hope for a shot-to-shot logic. Elsewhere, Collect-Serra creates the unconvincing illusion of an extended take by digitally connecting several, shorter shots together, even though the seams are obvious. By the time of the big reveal, the film has successfully lost our interest through its combination of banal storytelling and sloppy form. If the film is mostly disposable and too familiar, the initial face-to-face encounter between Neeson and Farmiga proves that talented actors can make lousy writing sound better. But that single moment is hardly enough to justify the rest.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review