The Card Counter

By Brian Eggert |

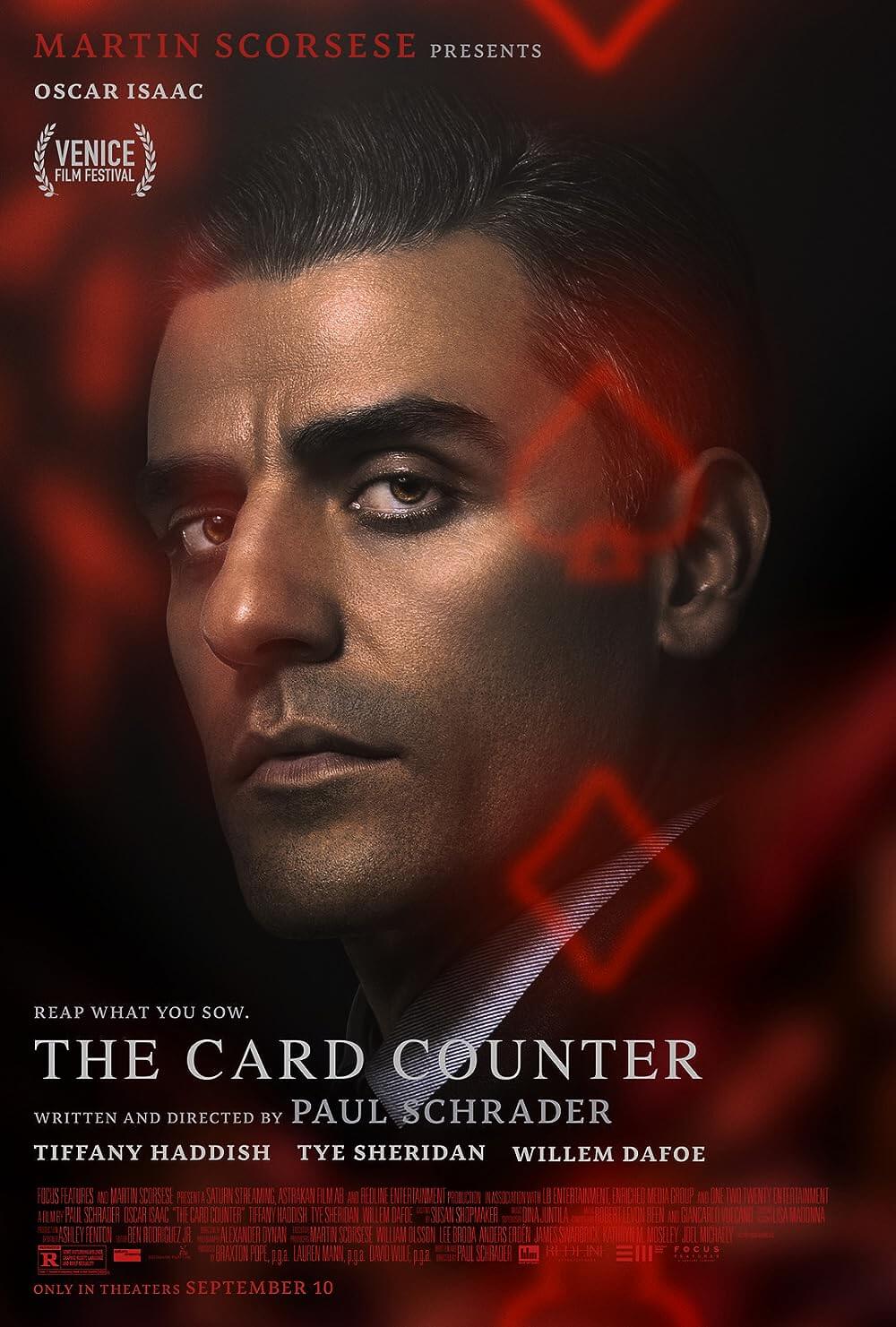

Paul Schrader’s The Card Counter stars Oscar Isaac as another of the filmmaker’s solitary men who, entrenched in routine, commits his inner thoughts to paper. He calls himself “William Tell” and has an austere existence. William travels around the country and plays cards. He likes blackjack most of all because it’s predictable; it relies on “dependent events,” he tells us in his voiceover, which comes straight from his journal. He never wins big, just enough to survive, and in doing so keeps himself under the radar. He stays in cheap motels, where he takes down the paintings, covers the furniture in white cloth tied down with twine, and makes the room into a blank cell. There, alone save for Johnny Walker, he writes. He writes about his time as a soldier in Abu Ghraib, his imprisonment for torturing inmates for the US Army, and his years in Leavenworth prison. Something resembling torment, guilt, and unease lingers behind his eyes, even though he demonstrates complete control. It’s a dynamic brilliantly captured by Isaac, an actor attuned to Schrader’s brand of inwardness.

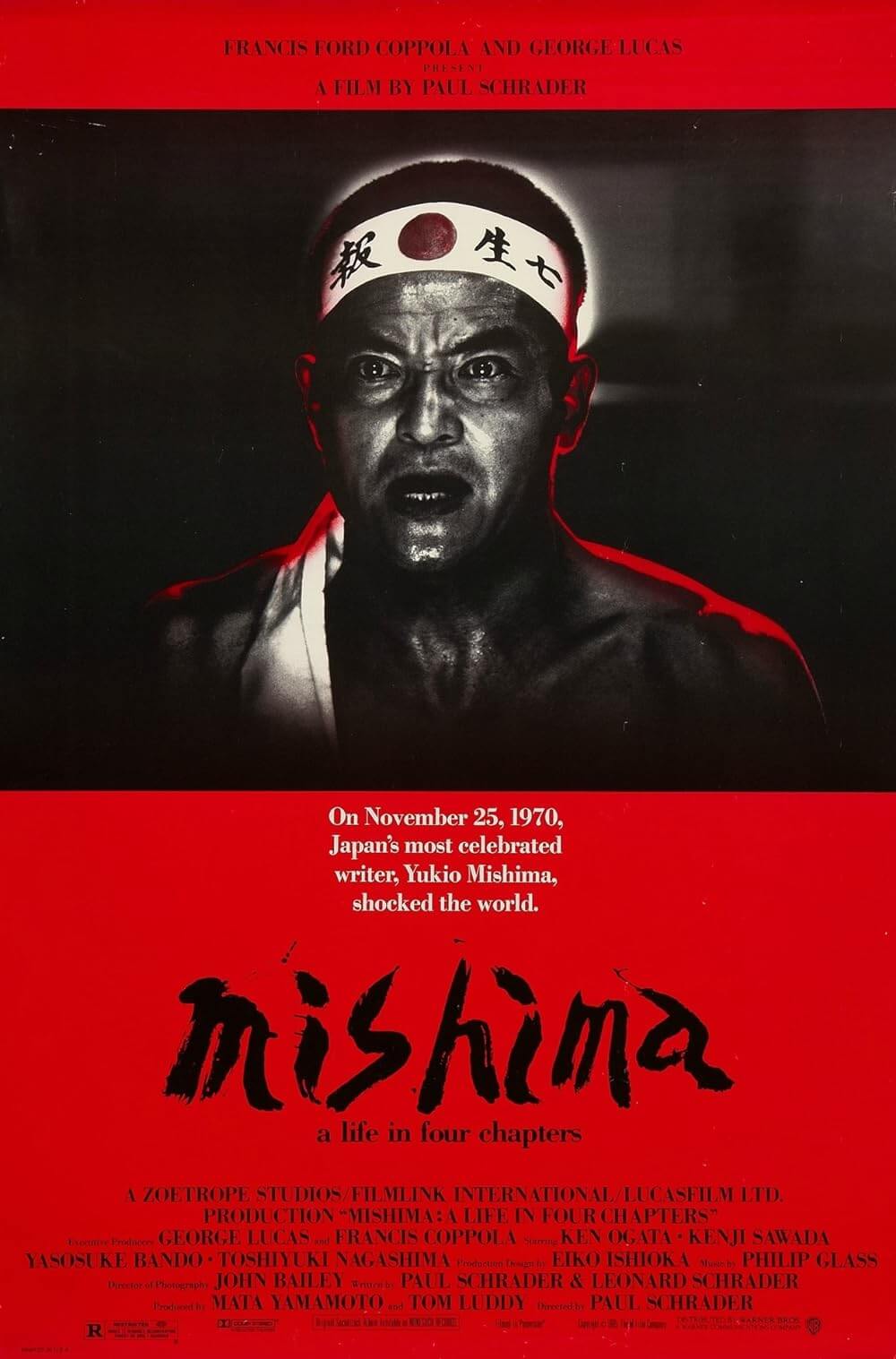

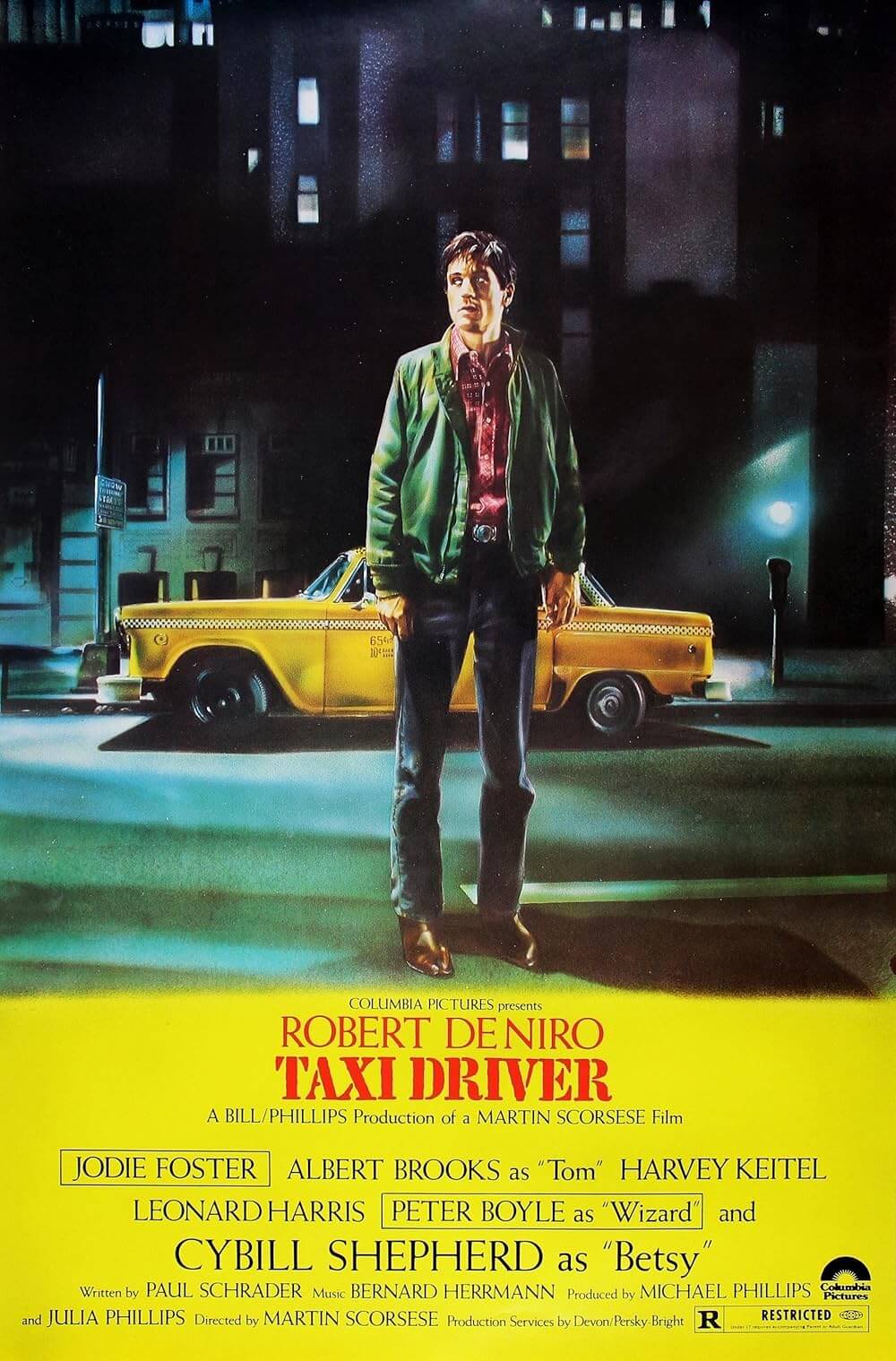

Many of Schrader’s protagonists have followed the example seen in French director Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951), about a holy man whose declining health and wavering faith eat away at him. Bresson has consistently influenced Schrader’s work, inspiring him to write his thesis, Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, a vital piece of film theory, and carry some of his ideas into his screenwriting and directorial efforts. Schrader’s obsession began with Travis Bickle, the unstable figure in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976). It continued with Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), his take on Yukio Mishima’s drive toward purity through artistic and physical control. Schrader’s films sometimes wobble and feel unfocused, as in Dying of the Light (2014) or Dog Eat Dog (2016). But when he returns to internalized characters who explore their disfunction in private words, it’s clear he identifies with the lone writer—the more self-destructive, corrupted, or frustrated with the world, the better. Most recently, Schrader’s First Reformed (2018), drawing closely from Diary of a Country Priest, told a similar story but with anger and a worldview that reflects the filmmaker.

The Card Counter cannot help but feel comparatively muted after First Reformed’s utter disenchantment and apocalyptic outrage in what might be Schrader’s most searing film. Still, his familiar obsessions and meditative approach lead to a fascinating character study filled with scenes of William—who names himself after the heroic figure that once adorned Hungarian playing cards—philosophizing about games of chance. But this is not a film about cards, like The Cincinnati Kid (1965) or Rounders (1998). William only plays cards because, he says, “It passes the time.” Of course, he’s good at it, but he also needs it—just like he needs to recreate the same conditions in every motel room. It’s the same reason he drives around and tosses in bed at night: his mind races. In the film’s sound design, we hear almost ethereal exhales—a deep breath released, as though William seeks to gain composure. It suggests he’s always on the verge. So William plans to go “around and around” playing cards until he can “work things out.” And in a statement that echoes his need to maintain himself, he tells someone, “I’ve met enough people.”

Some new people, as it turns out, give him a chance to find peace. The first is La Linda (Tiffany Haddish), an agent who helps poker players find financial backers to travel the tournament circuit. Then, there’s Cirk (Tye Sheridan)—“pronounced Kirk with a ‘C,’” he tells everyone—a dopey kid who has issues with his parents and wants to avenge his father’s death. Cirk recognizes William as one of the army’s convicted torturers and tries to enlist him in a revenge scheme against a contractor named Gordo, played by Willem Dafoe. Gordo taught the army its enhanced interrogation techniques, and putting them into practice drove Cirk’s father into self-destruction. For his part, William recognizes the anger inside of Cirk and resolves to help. He plans to bring Cirk along on a gambling tour, arranged by La Linda, and win just enough to pay off Cirk’s debts and get him into college. And saving Cirk means saving himself; it means there’s some hope that he, too, can escape his terminal need for isolation. William even allows himself to fall in love with La Linda.

Some new people, as it turns out, give him a chance to find peace. The first is La Linda (Tiffany Haddish), an agent who helps poker players find financial backers to travel the tournament circuit. Then, there’s Cirk (Tye Sheridan)—“pronounced Kirk with a ‘C,’” he tells everyone—a dopey kid who has issues with his parents and wants to avenge his father’s death. Cirk recognizes William as one of the army’s convicted torturers and tries to enlist him in a revenge scheme against a contractor named Gordo, played by Willem Dafoe. Gordo taught the army its enhanced interrogation techniques, and putting them into practice drove Cirk’s father into self-destruction. For his part, William recognizes the anger inside of Cirk and resolves to help. He plans to bring Cirk along on a gambling tour, arranged by La Linda, and win just enough to pay off Cirk’s debts and get him into college. And saving Cirk means saving himself; it means there’s some hope that he, too, can escape his terminal need for isolation. William even allows himself to fall in love with La Linda.

Those familiar with Schrader’s work will know better than to expect a happy ending. The Card Counter isn’t the kind of film where William’s fate rests on whether he can outplay his main competition at the poker table, an “America!” chanting goon who gloats over every fallen opponent. The tournament, even Cirk’s fate, is just another in a long line of distractions from William’s inner self. Whether he writes, drinks, or plays cards, he imposes self-imprisonment to atone for what he did at Abu Ghraib—and for what he found himself capable of doing. Dafoe’s character unleashed that side of William, seen in dizzying flashbacks, and William works to keep it contained. Though he excels at cards, the game will, and does, go on without him. Like many of Schrader’s characters, William’s fatalistic last act is a resignment, a sort of exhaling even, to his own incurably tortured identity.

Although Schrader literally wrote the book on transcendent cinema, what some might call “slow cinema,” he rarely employs that style in his films. The Card Counter unfolds at a leisurely pace, to be sure, but it also features disorienting scenes of horror and beauty. The ultra-wide-angle sequences inside Abu Ghraib bludgeon the viewer with heavy metal, barking dogs, and screams (“The noise. The fucking noise,” William says during an intense speech). Cinematographer Alexander Dynan’s roving camera follows William through a series of casinos and card rooms with William’s hypnotic confidence. Elsewhere, William and La Linda stroll around a Christmas light dreamland and hold hands, which is among the most endearing images in any Schrader film—enhanced by Haddish’s natural charm and appeal. The whole film is set to moody, droning music by Robert Levon Been of Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, whose sad voice and lyrics suggest that William will not escape himself. Rendered with his protagonist’s composure, the film makes only one misstep during an unclear climactic and bloody moment, whose details are less significant than their results.

The Card Counter is an excellent variation on persistent Schrader themes, blending his affinity for Diary of a Country Priest with another Bresson masterpiece, A Man Escaped (1956), about a man whose self-control is his salvation. William mentions more than once that he’s suited to prison—its routines and capacity to subdue his potential for violence. So he tries to recreate them in the outside world in motel rooms and on card tables. But eventually, his substitution proves inadequate, leading to a brilliant final shot: William and La Linda touching fingers on either side of prison glass. It’s a perfect metaphor for the layer that William must always keep between himself and the outside. And it’s at once the thing that keeps him from indulging his worst self and prevents him from making a full connection, which he desperately wants to make. This existential push and pull remains the conflict of many Schrader loners—the desire to be forgiven, seen, normal, and loved, even if that often proves impossible for such broken characters.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review