The Butler

By Brian Eggert |

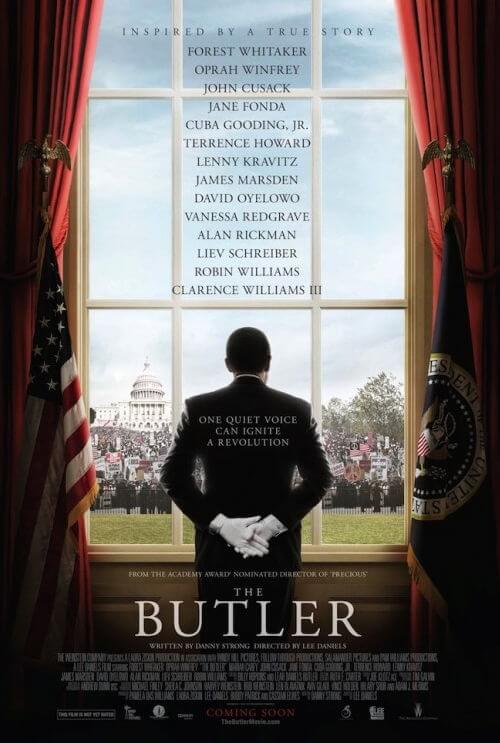

Renamed from just “The Butler” after a dispute with Warner Bros. (who have owned the rights to that title since their so-named silent comedy from 1916), Lee Daniels’ The Butler is a crowd-pleasing, Hollywood historical drama that refuses to take a firm stance on its subject—one of the most tumultuous periods in American history: the civil rights movement. The film was inspired by the real-life story of Eugene Allen, who served eight presidents as a White House domestic during his 34-year tenure. But instead of engaging the material in a factual, historical account of Allen’s life, the screenplay by Danny Strong is highly fictionalized and historically inaccurate. Though inspired by a 2008 article in The Washington Post called “A Butler Well Served by This Election,” the film adopts a structure more akin to Forrest Gump, wherein the titular character stands by the wayside and seldom participates in the monumental historical events going on around him.

Forest Whitaker stars as Cecil Gaines, whose upbringing on a Southern cotton farm where he witnessed the systematic abuse of his parents (David Banner and Mariah Carey) led to his education as a house hand. By the time he’s an adult, he has learned the careful art of serving white people and going unnoticed. At one point, he’s told, “You hear nothing. You see nothing. You only serve.” Eventually, his skill and adherence to these instructions find him a position at the White House. Now married with two children, Gaines dedicates himself to his Presidents. At home, his boozehound wife Gloria (Oprah Winfrey, who is never not Oprah) feels neglected, and his growing boys take divergent paths. His eldest, Louis (David Oyelowo), attends Fisk University, joins the Freedom Riders, becomes an activist alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. (Nelsan Ellis), and earns scorn from his father after becoming a Black Panther. Gaines just wants his boy to keep his head low as he does. Of the white man, he says, “It’s his world, we’re just living in it”—a position Louis cannot abide. Meanwhile, Gaines’ younger son (Elijah Kelley) enlists for Vietnam.

Moments on the Gaines’ porch or around the dinner table prove entertaining and blithe, if only because Gaines relaxes his normally stern, blank-faced sensibilities with a drink around friends. But not enough so he becomes a clearly defined personality. He still takes pride in how a room filled with white people feels empty with him in it. Even at home, he’s a stony sort, ever afraid to show his emotions like a stereotypical paterfamilias. He’s hard on his children and, for the better part of the film, inattentive to his wife. Whitaker is good in the role, and the supporting cast playing Gaines’ friends and family makes it seem as though Gaines has more personality than he does. Fellow White House butlers are played by an affable Lenny Kravitz and a potty-mouthed Cuba Gooding Jr. (whose dirty jokes and swearing are occasionally muted to ensure an audience-friendly PG-13 rating). Gaines’ marital discord, including Gloria’s infidelity with a sleazy neighbor (Terrence Howard), soon settles, but his ongoing rift with the more interesting Louis endures for the better part of the film. What it is that drives Gaines beyond being a good provider for his family is questionable; so is his participation, or lack thereof, in the civil rights movement.

Strong’s script follows Louis’ more impassioned path as an aside, the bulk of the film’s screentime spent on Gaines and his submissive White House station. Daniels seems readily aware that he’s making a commercial picture and, what’s more, standard Oscar bait from The Weinstein Company tailored to mass-appeal specifications. It’s rather sad to see Gaines and his fellow White House domestics finding such joy and eagerness in their obedient roles, but Daniels amps up several “serving the President” montages with enthusiastic soul music in the backdrop and offers few conflicted feelings about it. Posturing for more awards, Daniels has cast an impressive array of actors to play the Presidents of Gaines’ tenure: Robin Williams is Eisenhower; James Marsden is JFK; Liev Schreiber is LBJ; John Cusack is Nixon; Alan Rickman and Jane Fonda play the Reagans. Although each bit of casting is inspired, the roles are more throwaway impersonations than fully developed characters. Skipping over the 38th and 39th Presidents, the film offers yet another montage to cover what is considered a less interesting period of time—and based on the montage, for 12 years, Gaines does nothing else besides watch television, apparently.

Bookended with a segment where Gaines is to be honored by Barack Obama, the film makes him out to be a heroic figure. Whether or not you find Daniels’ film inspiring or, conversely, shameful, depends on how you view Gaines’ position as passive and subservient. MLK suggests that the Black man who serves white people defies stereotypes by proving to be hard-working and trustworthy. This safe, rather moderate, and certainly commercially appealing point of view makes Gaines and the film itself into a heroic portrait. Another perspective might be that, for the larger part of his life, Gaines never stands up for what he truly believes. He feels powerless because he has been trained to feel that way, and therefore he’s not an active protagonist but a flaccid, unengaging one. And yet, in the end, he’s awarded for this behavior and feels honored by the award. Time and again, Gaines swallows his pride when his White House supervisor tells him the Black employees will not receive the same wages as the white employees. Is it inspiring that it takes Gaines thirty years to finally demand a raise or sort of depressing? Of course, as Barack Obama himself has pointed out, because of bigotry and Jim Crow laws, there was only so far someone like Cecil Gaines could go. But is it heroic to be forced into a situation? No, it is tragic.

But Lee Daniels’ The Butler isn’t a tragedy; it’s a celebration of a man who avoided the greatest moments of the civil rights movement, while his son found various ways to fight the good fight for racial equality. The film is like several recent “feel-good biopics” such as The Blind Side, which was a film about a Black man filtered through the schmaltzy demands of a commercial, pointedly white moviegoing audience (ironically so, given Louis’ outspoken views in one scene about how Hollywood cinema caters to white people). And like The Iron Lady, this is a film that refuses to address the more challenging aspects of what is, in essence, a tragic, controversial subject. Daniels, who is best known for his unrelenting inner-city drama Precious, a film that puts its audience through the wringer emotionally while addressing crucial questions of race and social responsibility, has made a film without a backbone. That Daniels made Precious and also The Butler feels wrong somehow, as if Spike Lee had made Driving Miss Daisy after making Malcolm X and Bamboozled. What was Daniels trying to achieve? A history, a biography, or an account of a sociopolitical movement? The film is none of these. As a history, it’s lacking facts; as a biography, it’s missing personality and truth; as a political message, it has no standpoint whatsoever. In the end, our only certainty is that Daniels didn’t seem to know what he was trying to achieve, except possibly an Oscar or two.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review