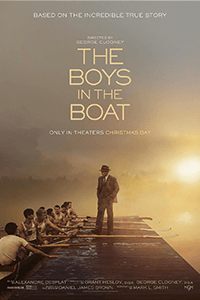

The Boys in the Boat

By Brian Eggert |

George Clooney’s ever more underwhelming track record as a director continues with The Boys in the Boat, a competent, flavorless adaptation of Daniel James Brown’s 2013 book. The film recounts the University of Washington’s rowing team’s journey to win the gold medal in the men’s eight competition at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Maybe that’s a spoiler. Regardless, this true story about Americans working hard through teamwork, technical ingenuity, and stick-to-itiveness—not only for glory but to show the Nazi regime they’re not the Übermensch they believe themselves to be, on a world stage for all to see—should be stirring stuff. Instead, its flatness recalls 1981’s Chariots of Fire, the dull winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture that’s not exactly a high point in Oscar history. After acquiring the project from The Weinstein Company, Amazon MGM Studios have teamed again with Clooney (whose The Tender Bar in 2021 was also an Amazon production), poising The Boys in the Boat for an awards season debut, on Christmas day no less. But it’s difficult to imagine the film causing much of a stir with either moviegoers or awards voters.

When writing about Clooney’s 2020 film The Midnight Sky, a blockbuster-sized sci-fi spectacle for Netflix, I asked, “Why does it feel so empty?” and complained that Clooney “never breathes life into the well-worn ideas.” Similar statements could be made about The Boys in the Boat. There’s nothing particularly wrong with the film, but there’s also nothing that distinguishes this purely functional production. It’s a vanilla ice cream cone, and not even French or New York vanilla, just generic vanilla—adequate, to be sure, but even a simple chocolate cone would have been preferable. When Clooney first started directing with Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002), the result was an irresistible scoop of sea salt and caramel; Good Night, and Good Luck (2005) supplied dimension with a bourbon-infused mocha chocolate chunk; The Ides of March (2011) was a dependable staple, a mint chip. Clooney’s flavor profile has been limited in the last decade, with forgettable but star-studded projects such as The Monuments Men (2014), Suburbicon (2017), and the aforementioned The Tender Bar.

The Boys in the Boat at least proves Clooney is consistent in directing recent projects that leave almost no impression. Though The Midnight Sky’s screenwriter Mark L. Smith comes from a background of horror and genre fare, he adapted Brown’s source material for The Boys in the Boat, and his straightforward screenplay adheres to the usual sports movie template with no surprises of note. In the wake of the Depression, the University of Washington rowing crew, consisting of middle-class college students, many struggling to get by, trains under coach Al Ulbrickson (Joel Edgerton, dependable as always) to qualify for the Olympics. Callum Turner, who’s not a screen presence I would call compelling in this underwritten role, stars as Joe Rantz, a student who must work part-time as a dockworker to pay for school. Rowing crew becomes a potential payday to ensure he can afford his tuition payment. A romantic subplot finds Joe courting a childhood friend (Hadley Robinson), which distracts him from learning how to achieve the necessary synchronicity with his fellow oarsmen, most of whom have thin personalities. But whatever interpersonal conflicts arise, the team works through them.

The production arrives with a stately appearance, capable and even-tempered, but utterly devoid of much stylization beyond the predictable Hollywood production’s look for a 1930s period piece. Cinematographer Martin Ruhe, who shot Clooney’s last two pictures, captures the rowing action in yellowish hues and earth tones, borrowing the occasional angle from Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia—her 1938 documentary covering the 1936 Olympics. Shooting in Berkshire and other locations around the UK, Clooney relies on the occasional CGI backdrop for dramatic scenes on the water, often neutralizing the transportive potential of the story. Alexandre Desplat’s score is unsurprisingly airy, punctuating early scenes with effortless flutes and light strings, while a soundtrack of jazzy numbers accompanies the inevitable training montages. Once the story moves to Berlin for the finale, the filmmaking maintains a measured clip; not even the presence of fascists can excite Clooney out of his stately mode. Elsewhere, the film borrows from classical Hollywood motifs, such as the big kiss at the train station. After Clooney’s Leatherheads (2008), a superior tale about 1920s football, the director’s penchant for old-timey sports movies is apparent; however, that comedy had more style and energy than his latest.

Given how predictably every aspect of The Boys in the Boat has been constructed, even if you didn’t know whether the team wins or not going in, you can guess the outcome. But this isn’t a film designed to leave moviegoers gripping their seats. It reminded me of the kind of film Robert Redford made in the 1990s, with the same quiet respectability; however, that comparison is unfair to Redford, whose A River Runs Through It (1992) and Quiz Show (1994) linger in the memory long afterward. Not so with Clooney’s work here. Still, there’s a lesson here about Rantz setting aside his ego for the greater good. If the coach’s claim that “rowing is more poetry than sport” is never quite justified with the workmanlike production, there’s at least a message that people working together to show a corrupt government—the Nazis, who attempt to finagle the competition in their favor—can prove triumphant. Surely, Clooney, a staunch anti-Trump celebrity, identified with this story, admiring the rowers for coming together against a singular oppressor. Smith’s screenplay doesn’t overemphasize the point, but it’s there. That’s something.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review