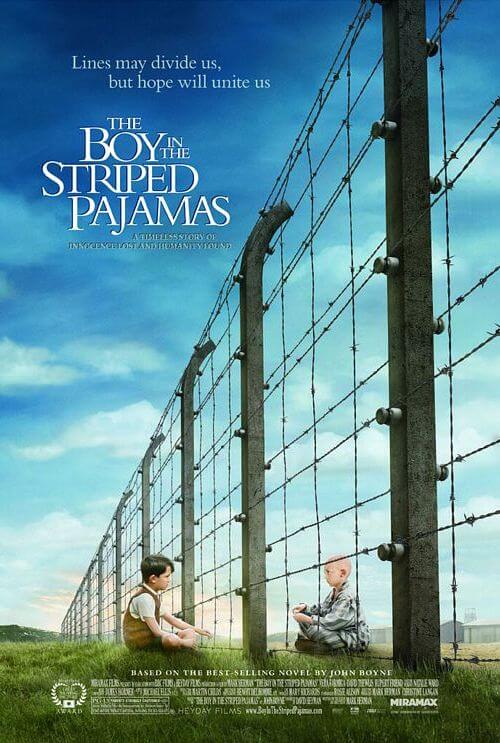

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas

By Brian Eggert |

Familiar themes of innocence lost, however overdone by Hollywood, can’t distract from the intensely dramatic effect of The Boy in the Striped Pajamas. The purity of childhood exists as the intent, and that might be all the film has to offer. If so, accepting it as a powerful depiction of children’s subjection during the Holocaust, and little more than a story plucking at our heartstrings, will suffice. The achingly sad story centers on an eight-year-old German boy during the early 1940s whose father is a Nazi. Bruno (Asa Butterfield) is an innocent, unaware of what Nazism means and oblivious to the then-current circumstances of his homeland. After receiving a promotion, his father (David Thewlis) takes the family from their extravagant home in Berlin to an icy concrete fortress in the country. Bruno is forced to abandon his friends back home, with whom he enjoyed silly children’s war games, and instead occupy his time with checkers, switching back and forth as both players out of boredom.

He asks his loving mother (Vera Farmiga) about the farm in the distance out his window. Can he play with the children in there? Why does everyone on the farm wear pajamas? Of course, this is no farm. Mother suddenly realizes the nature of Father’s promotion, and becomes emotionally distant, wanting to leave this place. Ever the dreamer, Bruno reads adventure books, as opposed to the Hitler Youth propaganda fed to his sister Gretel (Amber Beattie) by the family tutor. He hopes to explore the world someday, and like any child, embraces his blind curiosity, oblivious to where it leads him.

Through the backyard woodland resides “the farm,” where, behind barbed wire, sits a boy named Shmuel (Jack Scanlon). Bruno no more understands “Jew” than Shmuel comprehends “Nazi.” They’re just two boys of the same age. Neither understands why they’re supposed to hate each other. Sneaking sweets and playing checkers with his new partner whenever he can, Bruno begins to vaguely grasp the situation, but insomuch that he perceives some tension without a warning sign flashing red. Still, Bruno’s curiosity and good-heartedness take him places no child should go.

Butterfield and Scanlon handle their roles without the uncomfortable push of some child actors. They’re pure embodiments, outshining even the strong work by Farminga (Breaking and Entering, The Departed) and Thewlis (Naked, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban). So rarely do child actors allow the viewer to believe them fully, but these boys disappear into the film’s devastating world with aching effectiveness.

Another filmmaker might have staged the film differently, with a focus on suspense or retaining dramatic irony. Imagine a picture where the audience views the world from Bruno’s perspective entirely, where we’re not told his father is a Nazi, where we have to discover that tragic fact for ourselves. Director Mark Herman adapted his screenplay from the novel by John Boyne, and the presentation lays out the drama without a hint of uncertainty, every implication blatantly clear. This makes the film perhaps overly straightforward, but it also works for the intended outcome, as what feels complicated for a child is often deceptively simplistic for an adult.

The only mystery is the overall message. Stories like this are sometimes affecting enough in their unmistakable heartbreak, and if tragedy is all the film has to offer, Herman’s effort was a success. But does the film intend to argue anything, and if so, what? That children view the world through innocent eyes and remain incapable of intolerance? That hatred is taught, not born? Lessons should be learned from a story this profound. Punctuated with a finale that I won’t describe here, Herman’s film fades away, leaving us without a resolution to a number of conflicts that hold our interest throughout. Do Father and Gretel learn the error of their beliefs? How does the family live out the war? Will Bruno become a Nazi?

Resisting the belief that The Boy in the Striped Pajamas is just another story about wartime atrocities (Then again, how could there be “just” such a thing?), I allowed the film to soak for some time. After this period of fermentation, I have resolved that the story is quite basic, perhaps because the end leaves us empty and horrified instead of provoked. There’s no greater commentary or message is required beyond its warning about the innocence of youth and socially learned prejudice, mind you, just preferred. The film’s undeniable ability to shake its audience and remark on the Holocaust is enough. Footed in a simplistic story, the film is meager from a grand thematic perspective, particularly next to the substance of Au Revoir les Enfants, Schindler’s List, or Life is Beautiful, but still touches on important questions about the costs of human life and the dangers of hatred in a stirring, heart-wrenching tale.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review