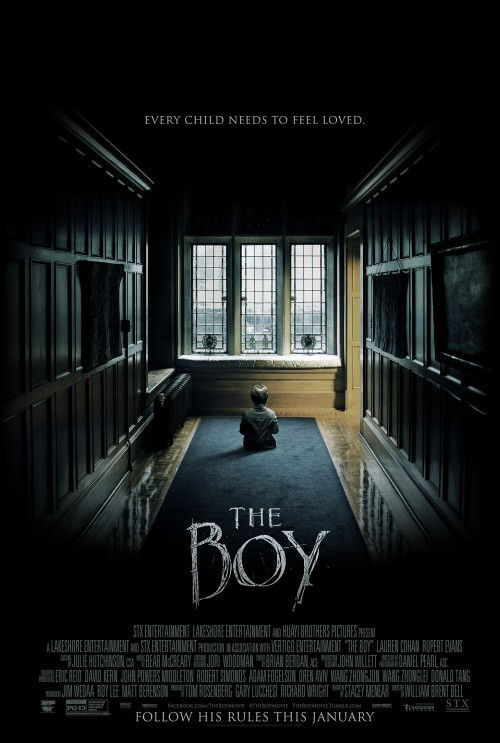

The Boy

By Brian Eggert |

More to my surprise than yours, dear reader, I’m writing a positive review of The Boy, a movie about an eerie possessed doll haunting a creepy gothic manor. While the concept alone may warrant a chuckle, the movie contains solid performances by its affable leads and a restrained style, uncommon for horror fare released in the dumping ground of January. William Brent Bell, the director of schlocky horror like Stay Alive (2006) and The Devil Inside (2012), and first-time screenwriter Stacey Menear, deliver a suspenseful story with likable characters and effective thrills. And the movie receives plenty of help from cinematographer Daniel Pearl and production designer John Willett, who render a sharp-looking visual presentation and ominous interiors.

But the movie is more exceptional for what it doesn’t contain: Although the trailer suggests this would-be supernatural thriller is something akin to 2014’s laughably bad Annabelle, the movie avoids many of today’s typical horror downfalls. Namely, there are few obligatory jump-scares (although there are a couple); no cheesy CGI to render those familiar pale, dark-eyed ghosts; and no predictable twists. Quite the opposite. The movie’s effective third-act twist, which will be discussed in detail later in this review (consider yourself forewarned), comes unexpected and welcomed. And then there’s the ending, which doesn’t feel like your typical horror movie ending, where something rushes at the camera or someone pops out of the back seat. Instead, The Boy chooses to be sinister, as opposed to in-your-face.

Lauren Cohan of AMC’s The Walking Dead fame stars as Greta, a Montanian who left her abusive boyfriend Cole to interview for a cushy babysitting gig in the English countryside. When Greta arrives at the manor of Mr. and Mrs. Heelshire (Jim Norton, Diana Hardcastle), she discovers that she won’t be watching over the Heelshire’s 8-year-old boy named Brahms; rather, it’s a life-sized porcelain doll the parents carry around and treat as they would their own departed child. At first, Greta thinks it’s a joke, but she quickly learns the Heelshires are quite serious—to the extent they have specific rules she must follow when handling Brahms, such as feeding him regularly, never throwing away his uneaten food, tucking him in, and kissing him goodnight. Brahms has apparently approved of Greta, so she gets the job. The situation becomes even creepier when they leave her alone with the doll for an extended vacation, and Mrs. Heelshire whispers “I’m so sorry” cryptically in Greta’s ear as they leave.

Rupert Evans plays Malcolm, a flirty local grocer who makes weekly deliveries to the home. He and Greta casually discuss the Heelshires, their late son who died in a fire and his reported oddities, their current China doll situation, and its sordid past. But as strange yet not necessarily malevolent occurrences take place around the manor, Greta gradually begins to believe the spirit of Brahms is somehow trapped inside the doll. An effective backstory about Greta’s abusive ex, who beats her and causing her to lose their unborn baby, helps establish some warranted sympathy for the child’s spirit, if indeed it does exist. Greta notes the doll seems to move at times; elsewhere, she receives scratchy calls she assumes are Cole. When it turns out to be a child’s voice, she feels bonded to Brahms and begins following the rules to the letter out of sympathy for the boy’s trapped spirit.

(Skip this paragraph should you wish to remain unspoiled.) On the periphery, Brahms’ parents have killed themselves and written an unopened letter to Greta explaining why. We know that Greta is somehow doomed, yet we’re not quite sure how. Meanwhile, things with Cole (Ben Robson) go south as he shows up at the Heelshire manor, only to find Greta taking care of a porcelain doll like it’s a real boy. Has she gone crazy? She’s even convinced Malcolm that Brahms’ spirit is real with some persuasive evidence. Being a white-trash jerk, Cole gets rough and smashes the doll. By now, the slow-burning movie has persuaded us that Brahms’ ghost will now wreak havoc. And sure enough, the house begins to shake and strange sounds come from behind the walls. But it’s not Brahms’ spirit; it’s Brahms, all grown up, living in the walls. He was holding his parents hostage and auditioning women to be his new caretaker. He appears tall, covered in body hair, and an overgrown beard beneath his porcelain doll mask. The final scenes involve a terrifying chase around the house, which Brahms refuses to leave, leading to a satisfying conclusion.

So there it is: the twist that makes The Boy surprising and unexpectedly scary. To be completely forthright, The Boy isn’t a great movie. But it defies our expectations for the sort of cinematic garbage that usually hits theaters in January. Horror movies are especially bad in January (just look at The Forest, which opened two weeks prior). However, this movie takes a typical 1980s-style twist that hasn’t been used for years and applies it here, much to our surprise. It reminded me of the first Friday the 13th, where the spirit of Jason Voorhees supposedly haunted Camp Crystal Lake, but in reality, it was his crazed mother all along. In an age where Hollywood is obsessed with demonic spirit possessions, poltergeists, and other ghostly hauntings, The Boy is a refreshing change of pace with fine acting and an effective production. It won’t tax your brain cells, but you’ll be entertained.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review