The Boxtrolls

By Brian Eggert |

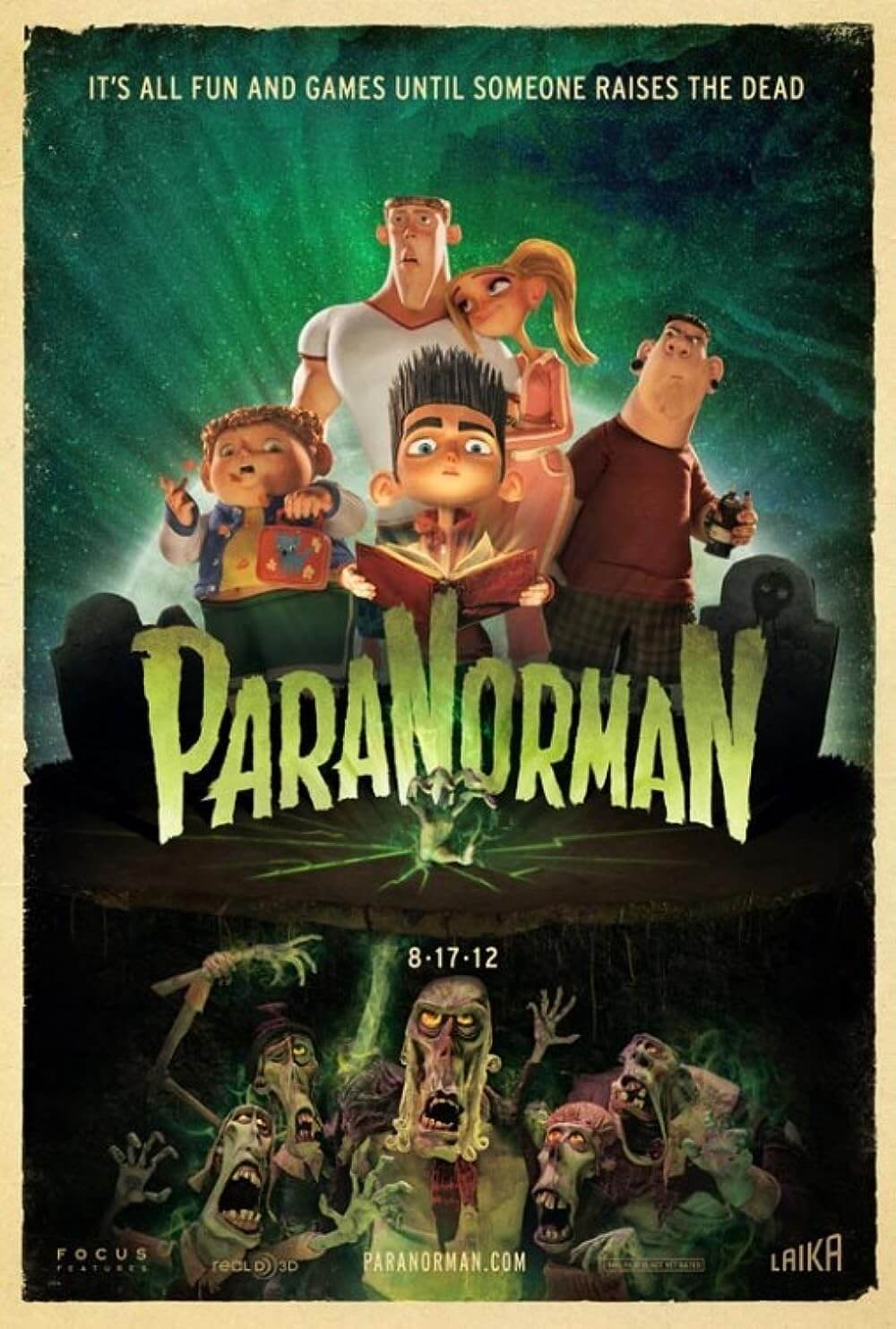

If Dickens ever chose to explore adorable monsters living under the city streets of London, you might have got something like The Boxtrolls, a macabre little story about bug-eating creatures with a knack for building gizmos. From Laika, creators of Coraline and ParaNorman, comes another stop-motion animated picture that combines the pointedly British sensibilities of Wallace & Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit and Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. Based on the book Here There Be Monsters! by Alan Snow, the gorgeously assembled film concerns the silly, the grotesque, and sometimes the nasty, and it may be a bit too morbid for some. But co-directors Anthony Stacchi and Graham Annable bring together something that contains familiar enough themes for anyone to relate, with a hint of steampunk design, a note of inspiration from Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, and an affinity for cheese. Who could ask for more?

The four-fingered, gnome-like boxtrolls inhabit the subterranean world beneath Cheesebridge, a small what-looks-to-be nineteenth-century city built on sharp slopes. Each boxtroll wears a hermit crab shell in the form of a cardboard covering, which they are careful never to remove, and which also signify their names: Fish, Wheels, Sparky, and Fragile are just a few. At night, they emerge from their dwelling to find broken gadgets and do-dads that they cart back to their underground cave, where they assemble new contraptions to entertain themselves. Harmless, gentle creatures, they’re dreadfully misunderstood by the humans above. Having been blamed for kidnapping the Trubshaw baby boy, the boxtrolls are now hunted by a scallywag named Archibald Snatcher (Ben Kingsley, in a tour de force vocal performance), who concocted the snatching to gain entrance into the upper crust’s White Hat society—which meets regularly to sample the finest curdled comestibles offered in Cheesebridge.

The Trubshaw baby, now adopted by the boxtrolls and renamed Eggs for the box he wears, is a boy (Isaac Hempstead Wright) not unlike Tarzan, raised away from human society and oblivious to its customs. When Eggs begins to wonder why the pacifist boxtrolls aren’t questioning why they’re being hunted and why their numbers keep dwindling on every night excursion, he encounters Winnie (Elle Fanning), a human girl curious about the macabre mythology of boxtrolls. She’s also daughter to the biggest bigwig of them all, Lord Portley-Rind (Jared Harris), who plays host to the other White Hats and concerns himself more with cheese than his daughter’s penchant for troublemaking. And in due course, Winnie’s plucky nature seeks to expose Snatcher’s scheme and announce Eggs as the long-disappeared Trubshaw baby in a sequence at a dance. There’s so much going on in this scene that the stop-motion application, enhanced at times by CGI, requires a genius-level arrangement and preplanning.

Meanwhile, the villainous Snatcher has a dastardly plan; he’ll do just about anything to get into that prized cheese tasting room savored by the White Hats. Between cross-dressing as a resident sexpot Madame Frou-Frou (who sings the Trubshaw baby story in a hilarious tune composed by Monty Python’s Eric Idle) and building a maniacal machine to rid Cheesebridge of boxtrolls forever, Snatcher becomes The Boxtrolls‘ most fascinating character. He’s surrounded by three henchmen: one of them, called Mr. Gristle (Tracy Morgan), has a diminished and sadistic manner; but the other two, Mr. Trout and Mr. Pickles (Nick Frost, Richard Ayoade), wax philosophical and discuss “the duality of good and evil” against the likelihood that they’re heroes of their own story. Most ironically, we learn Snatcher’s plan is all for naught since his aggressive cheese allergy results in a disgustingly monstrous reaction that requires leeches to de-swollen his face and lips.

The approach and screenplay by Irena Brignull and Adam Pava emphasize a number of familiar themes and plotlines throughout. The notion of misunderstood monsters paired with a human child comes from Monsters, Inc.; an under-dweller hero who questions where he belongs reminds us of Ratatouille; the cheese-centric characters recall Aardman’s Wallace & Gromit work, created by Nick Park; WALL•E‘s social commentary about the necessity of refurbishing garbage is apparent; and the cute, chattering monsters are reminiscent of the Minions in Despicable Me. Except, there’s British-inflected humor redolent of Monty Python and a decidedly abnormal undercurrent throughout that makes The Boxtrolls feel unique in its field. Take Snatcher’s demise, which I won’t detail here, but frankly, it dropped this critic’s jaw with a sense of I can’t believe that just happened! Few animated films have made me laugh harder from their unexpected and eccentric goings-on, and few in recent years have proved so memorable.

Of course, The Boxtrolls is a visual wonder, with every tangible building and character capturing our eye to an almost distracting degree. Truly appreciating the film may require two viewings, the first to get through the story, the second just to observe the immaculate detail carefully put together in every frame by the stop-motion animators. In a riotous post-credits sequence, Mr. Trout and Mr. Pickles ponder whether giants are controlling their every move and spending an entire workday in the blink of an eye, making 24 small adjustments for each second of screentime. The scene, which blends an actual animator with the animated characters, reminds us of the craftsmanship and artistry that goes into such a picture and makes us fall in love with it even more. And despite all its similarities to material you’ve seen before, The Boxtrolls contains so much charm in its squalor, so much joy in its decrepitude, that the black humor and beautiful animation cannot help but leave an audience delighted.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review