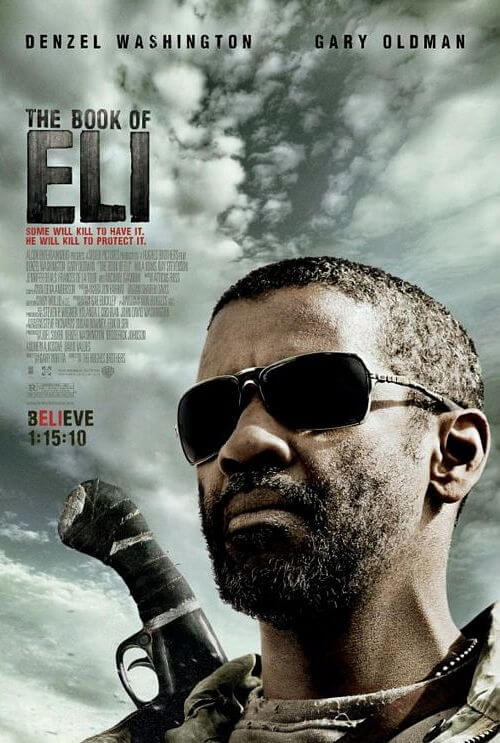

The Book of Eli

By Brian Eggert |

Thanks to the posters and trailers that boast “Religion is Power” and “Deliver Us,” you should have figured out by now that the book in The Book of Eli is The Bible. The story takes place some thirty years after a nuclear war that was provoked by religious zealotry. As a result, the postwar peoples gathered all the Bibles and burned them. However unlikely, now there’s only one left, and it’s in the possession of a lone samurai of the American post-apocalyptic wasteland. Eli, played by the cool and contemplative Denzel Washington, walks the scorched earth westward on a mission given to him by a God.

The terrain is barren and colorless, and the Sun always seems to be shining its harsh, poisonous rays. The wretched landscape is peppered with survivors scrounging for leftover supplies, water, and human meat. On his voyage, Eli meets a number of characters played by big actors in small, pointless cameos—Tom Waits and Michael Gambon to name two. Things get worrisome when Eli watches as a motorcycle gang murders and rapes a couple on the road, taking their supplies; he vows to continue on his path and not get involved. The gang brings the couple’s books back to their ringleader in the town ahead, a power-monger named Carnegie (Gary Oldman) who desperately searches for a copy of The Bible. Of course, Carnegie soon learns of Eli’s book and trouble ensues.

Eli and Carnegie are the same. They both know The Bible’s power, but they want to use it in different ways. Eli just wants to continue with his mission, which he claims was given to him by The Voice. The crimelord Carnegie wants to become the next Billy Graham and lead the world’s collective stragglers into a new civilization if only to enjoy the power that comes with the position. The movie turns into an actioner when Carnegie sends hordes of goons to get Eli’s book, and our hero, teamed with Carnegie’s sympathetic and religiously curious employee Solara (Mila Kunis), kills just about all of them.

The most admirable aspect of the production is its use of Washington in a samurai-esque role. Traveling the spare road like a ronin with a purpose, Washington is very much a singular, Toshiro Mifune-like character here—more of an action hero than he’s ever been before. The fight scenes are clearly described and enjoyable to follow, with the camera placed at a distance so the audience can see every detail of the violence as it unfolds. It’s not muddled with extreme close-ups and Shakicam photography. We watch as Eli’s massive knife cuts through people, or as Eli takes down a dozen armed men with a pistol, and the Hughes Brothers keep us aware of space and setting throughout, never losing us in their formal flourishes.

There’s a big reveal concerning Eli in the final moments that you may not see coming. Though the twist won’t be described here, those of you who see the movie can imagine how much more powerful the film would’ve been had we learned Eli’s secret much earlier in the film. It may have elevated the story to the level that filmmakers were doubtless trying to achieve but ultimately didn’t. What spoils the movie is that the audience is left wondering what purpose The Bible will have given where the story leaves off. Was the reason for Eli’s journey to spread the Word of God, or to simply supply the religious perspective to a group of historians gathering data on what humanity used to be? What significance do Eli’s actions have in the grand scheme?

Compare The Book of Eli to last year’s very similar The Road, and you’ll find there’s no comparison at all. Everything that John Hillcoat did with emotional gut punches and stark, introspective scenes, the Hughes Brothers do with action and blind faith in religion. Hillcoat’s film knew that in this fried, all-hope-is-gone world, to put your faith in religion didn’t help much, that The End was coming no matter what you believed. The Hughes Brothers’ film thinks just the opposite—that religion will save everything because it has the ability to collect people and force them to take action in the name of God. Carnegie believes this with every fiber of his being, and perhaps he’s right. Undoubtedly, audiences will decide which film they prefer based on their own religious convictions.

The Hughes Brothers have made an admirable film. They’ve beautifully photographed a gray, blasted desert wasteland and made it completely believable. They keep their composure in allowing their story to play out; their approach is patient but, in the end, rather enigmatic about what kind of story they want to tell. Is this a Yojimbo tale—a yarn about a lone badass traveling through town and leaving a trail of bodies behind him? Or maybe it’s something more like Tolkien, a vast journey made by a meditative traveler? The Hughes Brothers try for both because they couldn’t decide, and so the combination of their confused purpose, heavy violence, and potentially significant themes make the story feel confused. While enjoyable, it’s unclear what audiences are supposed to take away from it.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review