The Blair Witch Project

By Brian Eggert |

With the benefit of hindsight, writing a review of The Blair Witch Project seventeen years after the fact remains a thorny prospect. I can choose to look at the horror movie as a whole, as objectively as possible; or I can simply judge my initial experience seeing the movie in 1999; or I can even consider my subsequent viewings after the rash of “found footage” offshoots it inspired have worn down the gimmick, rendering it no longer effective, if it ever was. After all, more substantial narratives have improved upon the movie’s unsatisfying ending and rather annoying visual experience in the years since its release, even while employing the same “found footage” structure (Chronicle and The Bay come to mind). And though filmmakers Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez didn’t invent the genre—Ruggero Deodato’s disagreeable 1980 gorefest Cannibal Holocaust deserves that crown—they popularized it.

My take on the film, I suppose, will be a combination of these approaches. So let’s begin with a little background. Much talked-about upon its release, The Blair Witch Project debuted at the Sundance Film Festival and was purchased by Artisan for release the following summer. Shot on the ultra-cheap over eight days in a Maryland forest, Myrick and Sánchez set out to create something people would believe actually happened. They were fascinated by documentaries involving paranormal research and witchcraft. Their production company, Haxan Films, was named after Benjamin Christensen’s 1922 documentary Häxan, in which dramatized sequences recreate haunting moments of torture and ritualistic killing—terrifying stuff. They hired unknown actors to handle the cameras themselves and shoot their experiences in the woods; it was an entirely improvised experience scenario, and the directors interacted with (e.g. messed with) their performers from a distance, resulting in some very authentic responses. Hundreds of hours of footage were cut down to an 81-minute feature.

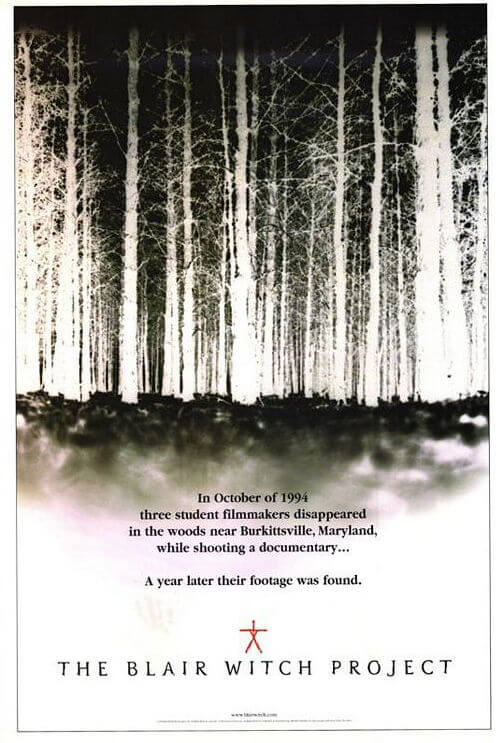

When it came time to release the movie, Artisan’s clever marketing campaign suggested the events depicted therein were real. The movie’s official website (www.BlairWitch.com, still going strong) contained faux newsreel footage and interviews attesting to its authenticity and the real-world existence of the Blair Witch legend, insisting, “In October of 1994 three student filmmakers disappeared in the woods near Burkittsville, Maryland, while shooting a documentary. A year later their footage was found.” Several articles in otherwise respectable magazines and newspapers featured similar “Real or not?”-type articles about the movie. Meanwhile, a so-called documentary appeared on cable television, detailing the origins of the Blair Witch in Burkittsville, formerly Blair. At the time, I was in high school and can attest to the widespread belief that The Blair Witch Project was real, as though any studio large or small would release a supernatural snuff film onto the public.

Indeed, when I first saw the film on opening weekend at the Uptown Theater in Minneapolis, MN, the audience buzzed with belief and anticipation. And though I remained skeptical, I cannot deny the movie’s initial impact, especially during the first hour of footage. All playing themselves, amateur filmmakers Heather Donahue and Josh Leonard are joined by a soundman Michael C. Williams on their investigative project into the Blair Witch. The backwoods folktale involved a mysterious figure in the woods, missing children, abnormally thick arm hair, and wooden stick figures. When they set up camp in the Blair Witch’s supposed terrain, the filmmakers experience unsettling sounds in the night, wake up to curious rock piles around their campsite, and quickly become lost. Tensions run high as the situation causes our trio to turn on one another, leading to one disappearance and an abrupt ending that suggests everyone involved in the expedition died horribly.

The Blair Witch Project’s most effective quality remains its use of our imagination to build up otherwise silly things into horrifying omens. For example, Josh finds some slime on his backpack. One might just attribute this to slugs or some other organic residue from the forest, but because Josh keeps obsessing about it, we cannot help but feel he was marked by something out there. “Why me?” he keeps asking, as though he hopes to perpetuate a self-fulfilling prophecy. Likewise, small piles of rocks and twig figures have never seemed so scary, because we remember the movie’s initial scenes where the crew records the convincing tales of local bumpkins. These quaint, average folk take hearsay as fact and wholeheartedly embrace the rural legend; the seed has been planted for our imagination to later run wild with terrible possibilities.

Unfortunately, what appears onscreen never amounts to much beyond psychological torment. The dark and dense forest setting, consistent shaky handheld camerawork, and footage shot on video and 16mm leave it impossible to make out anything of significance. The characters run through the woods and shout things like “Did you see that?” but the answer is no—no we did not. The camera didn’t see it, and so neither did the audience. Every “ghost hunter” and “paranormal investigator” on television has applied the same tactic. Ultimately, the audience never sees a thing, and the movie remains dependent on what we believe the characters see, as opposed to what we see. By the time the rushed final sequence in a rundown woodland shack comes to pass, we hear Josh’s screams as Mike stands in a corner awaiting execution from who-knows-what, and Heather is presumably bludgeoned to death.

When the screen went black and the end credits began to roll, I remember groaning in disappointment along with most of the theater. “That was it?” many spectators complained. I remember thinking, Who was able to safely recover this footage from the basement of the Blair Witch’s house? Was that person tormented too? I also remember thinking the ending robbed the viewer of any emotional closure, but not in a manner that proves satisfying. Many horror films over the years have ended with everyone dying, yet they were much more substantial experiences dramatically. The experience engineered by Myrick and Sánchez has almost no shelf life whatsoever beyond its runtime; after that, all suspension of disbelief has been shattered and the rush is over. Nevertheless, The Blair Witch Project received extremely positive reviews (it still holds an 86% rating on RottenTomatoes), earned a cult following, and became something of an urban legend itself—at first, anyway. Later that same year, it was nominated for a Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Picture, largely due to backlash about the unsatisfying ending.

Amid the accolades, Roger Ebert specifically praised the way the movie exploited our fear of the unknown. And while the unknown remains a compelling force in the horror genre’s best entries (Halloween, The Thing, The Mist, Rosemary’s Baby, etc.), those examples each demonstrate that believing in the unknown is dependent on seeing… something. Sticks and stones and slime don’t amount to much, whereas a shape in the woods or a brief snapshot of a shadow may have elicited our fear beyond the end credits—[Rec] (2007) and its remake Quarantine (2008) are fine examples of this. The Blair Witch Project lost me the first time, after the screen cut to black; during subsequent viewings, I have been even less engaged. As a critic, I must review the overall experience and not merely how frightened I was during the first hour. As a film historian, I must acknowledge that the movie’s phenomenon has come and gone, while its experience and reputation have not aged well.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review