The Black Phone

By Brian Eggert |

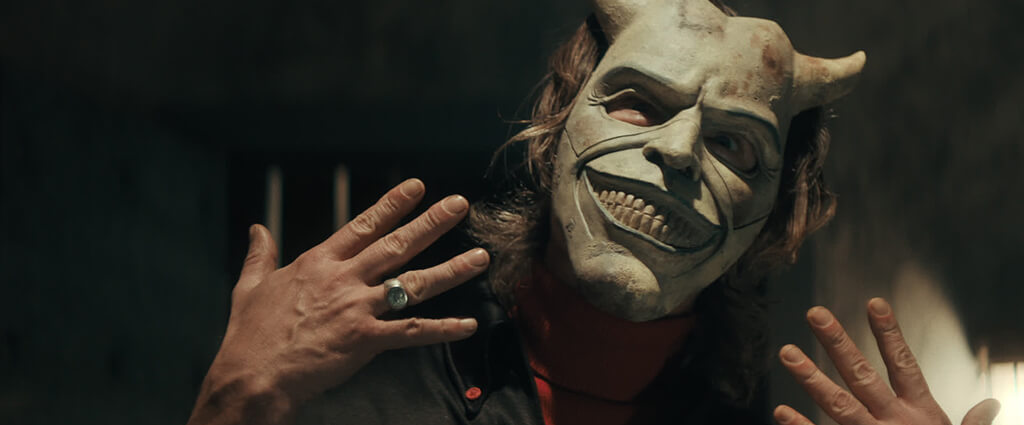

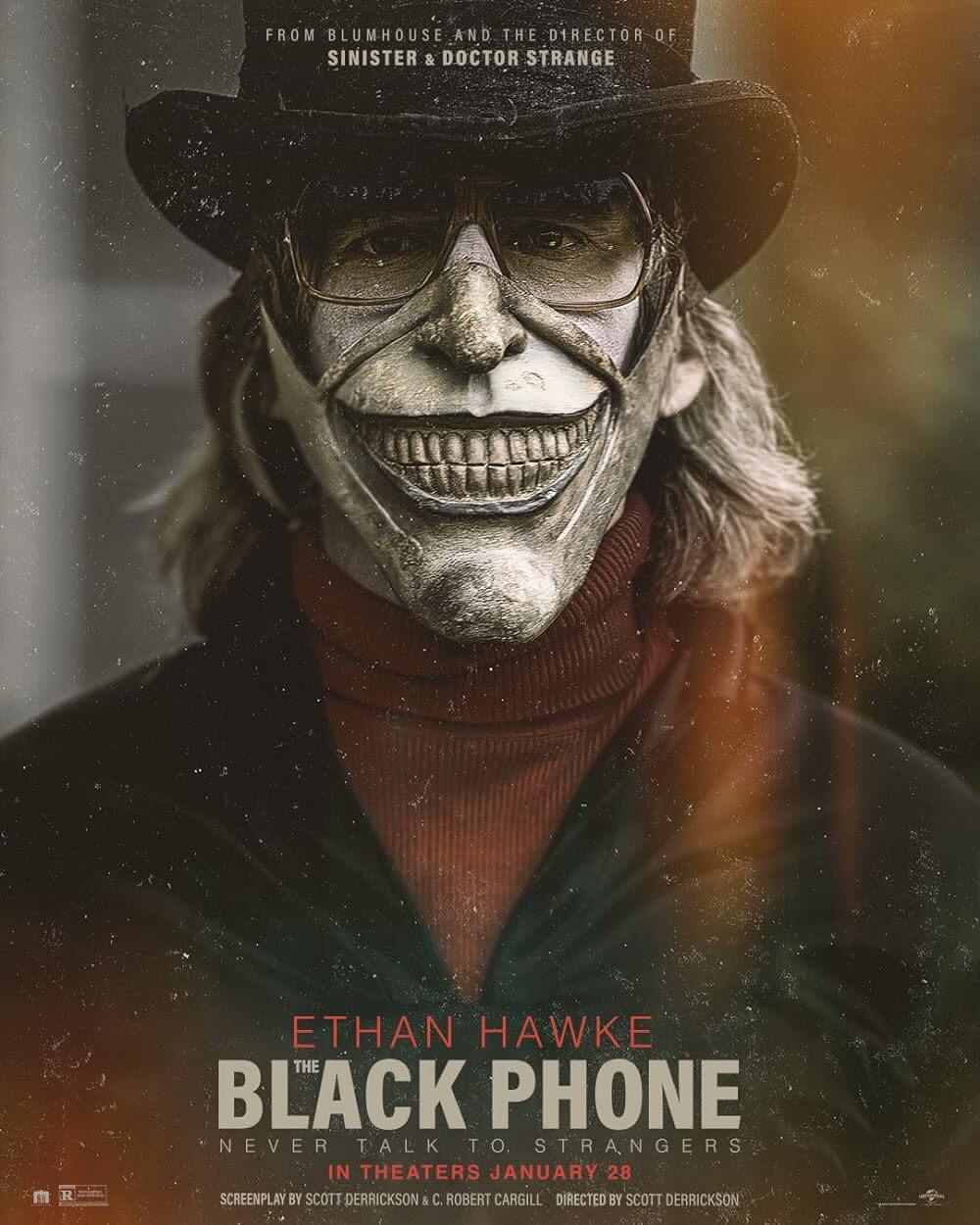

In The Black Phone, Ethan Hawke plays a child murderer, The Grabber, among the spookiest movie maniacs in recent memory. His modus operandi: he scours a small town in northern Denver for children. The film takes place before the Satanic Panic ratcheted paranoia about children’s safety, before Amber Alerts, and before cops became a regular fixture in schools—when schoolyard fights were bloody, and children roamed free on the streets, getting themselves into trouble, or worse. The Grabber drives a black van and pretends to be a magician, luring and drugging his victims. He locks them away and, after days of torturing them with insidious games involving his eerie masks, he kills them in ways left to the imagination—and the film is scarier for it. The Black Phone forgoes explaining his motivations or why he wears a mask, though his behavior supplies clues. No shrink appears in the final scene and expounds the killer’s motivations à la Psycho (1960). Whatever his deal is, The Grabber’s secrets remain unspoken and only hinted at for the viewer to decipher. In an age where horror movies over-explain every wrinkle, the ambiguity here recalls classics from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) to Halloween (1978) in their willingness to leave some mystery about the nature of the beast.

Director Scott Derrickson returns to his horror roots with The Black Phone after helming Doctor Strange (2016) for Marvel. He stepped away from their sequel—this year’s Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, which landed with Sam Raimi—for something smaller yet more personal. After all, before detouring into the MCU, Derrickson made low-to-mid-budget horror movies almost exclusively, ranging from The Exorcism of Emily Rose (2005) to his Blumhouse hit Sinister (2012) to Deliver Us from Evil (2014). Now he reteams with screenwriter C. Robert Cargill, with whom he co-wrote both Sinister 2 (2015) and its predecessor. Their adaptation of Joe Hill’s short story, from the author’s 2005 collection 20th Century Ghosts, returns Derrickson and Cargill to the familiar company of producer Jason Blum. But if Derrickson has made his best film—and he has, horror or otherwise—it’s because he’s putting himself into the story and using Hill’s source text as a foundation.

Derrickson obviously expanded on Hill’s 7-page story, but he also takes the basic concept and makes it his own. The material—a child medium, ghosts, nostalgia, a psychotic killer of children—has the distinct flavor of various Stephen King novels, namely It. Of course, Hill acquired this DNA from his best-selling father. However, the director fleshes out existing characters, adds new ones, and introduces themes and locations with personal resonance. For starters, the setting in northern Denver, 1978, echoes Derrickson’s childhood. While promoting The Black Phone, the director has talked at length about his rough upbringing marked by bullies and violence in Colorado, so he takes ample time and care in establishing this milieu. He doesn’t rush into scares but instead gives texture and builds emotional bonds that will pay off later. Vicious bullies hound the young Finney (Mason Thames) at school, and he’s often rescued by his little sister Gwen (Madeleine McGraw) or the school’s resident kid tough-guy (Miguel Cazarez Mora). When the children fight, they beat each other to a pulp. When they talk, they swear like sailors. And at home, Finney and Gwen, who share a tender bond, must contend with their own bully—their father (Jeremy Davies), an alcoholic widower who uses a belt on Gwen in a disturbing scene.

The Black Phone portrays an unforgiving world for children. Around town, a rash of child disappearances attributed to The Grabber has put everyone on alert. Derrickson instills a mood of dread in scenes where a child notices a dark figure in faux magician garb, driving a van with “Abracadabra” stenciled on the side, and the shot fades away. The police have no leads. Gwen thinks she might have a clue from her clairvoyant dreams—which look like Super 8 home movies—a skill inherited from her late mother. But her disapproving father forces her to hide her talent and repeat, “My dreams are just dreams.” Nevertheless, her dreams will come in handy after The Grabber abducts Finney and locks him in a soundproofed concrete basement with little more than a dirty mattress and a disconnected rotary phone on the wall. Alone and desperate, Finney receives calls from The Grabber’s victims from beyond the grave. They offer him detailed advice on how to escape or get the upper hand on his captor. While the phone’s origins and questions about the afterlife remain unclarified, Derrickson and Cargill heighten tension with Finney’s situation and the looming danger of their child killer.

The Black Phone portrays an unforgiving world for children. Around town, a rash of child disappearances attributed to The Grabber has put everyone on alert. Derrickson instills a mood of dread in scenes where a child notices a dark figure in faux magician garb, driving a van with “Abracadabra” stenciled on the side, and the shot fades away. The police have no leads. Gwen thinks she might have a clue from her clairvoyant dreams—which look like Super 8 home movies—a skill inherited from her late mother. But her disapproving father forces her to hide her talent and repeat, “My dreams are just dreams.” Nevertheless, her dreams will come in handy after The Grabber abducts Finney and locks him in a soundproofed concrete basement with little more than a dirty mattress and a disconnected rotary phone on the wall. Alone and desperate, Finney receives calls from The Grabber’s victims from beyond the grave. They offer him detailed advice on how to escape or get the upper hand on his captor. While the phone’s origins and questions about the afterlife remain unclarified, Derrickson and Cargill heighten tension with Finney’s situation and the looming danger of their child killer.

Hawke is seriously creepy in The Grabber’s various grinning or scowling horned masks, designed by legend Tom Savini. Armed with a high-pitched laugh and disturbing remarks (“I will never make you do anything you won’t like”), the villain has some apparent issues about what’s beneath his disguise. Derrickson hints at this by carefully avoiding Hawke’s entire face, except for a few brief glimpses that suggest he would rather stay concealed. Gradually, Finney works toward a confrontation with the help of ghost callers. The suspense builds along with the boy’s desperate struggle against the overwhelming threat. If the strangely funny side character Max (James Ransone), The Grabber’s brother, seems out of place in this grave scenario, his presence later hints at Derrickson’s commentary on the products of violent households. The Grabber’s sadistic “naughty boy” game might suggest that he came from an abusive home and revisits his childhood beatings on his victims. The child murderer and his troubled, cocaine-snorting brother establish a dramatic parallel with Finney and Gwen, as perhaps both sets of siblings are children of abusive homes.

Derrickson was also responsible for Bagul, the absurdly named and ridiculous-looking baddie in Sinister, a demon whose laughable appearance derailed an otherwise tense experience. Watching The Black Phone, it’s easy to imagine the material falling apart with another actor behind The Grabber’s mask, but Hawke sells the twisted mind. It’s also tempting to dismiss the result as another in a long line of Blumhouse horror movies dependent on the usual bag of tricks. But the commonplace tactics have been used to such expert effect here—reminding us that jump scares aren’t the problem; it’s how they’re used. Cinematographer Brett Jutkiewicz shoots in a grimy ‘70s-yellow palette and renders darkness with clarity, while editor Frédéric Thoraval allows scenes room to breathe. Here’s a movie whose pacing and shocks will play the audience, especially crowds. If it’s not the scariest movie of 2022, it nonetheless caused much jolting, gasping, and shouting at the screen in my preview. It’s not a film that will leave you shaken to the core, but it reminds us that it’s fun to be scared. Despite the subject matter, there are moments of levity too. Gwen’s foul-mouthed attitude and frustrated prayers (“Jesus, what the fuck?”), delivered by the show-stealing McGraw, remain a regular source of humor.

In the end, The Black Phone is also impressive for what it isn’t. Take how Derrickson and Cargill resist the all-too-common urge to set up a sequel or inject one last jump scare before the end credits roll, cheapening the integrity of what came before (another mistake in Sinister). It’s refreshing to watch a self-contained horror story for a change and not wonder about the next one. The filmmakers also avoid needless exposition and trust the viewer to make connections themselves, even while Derrickson deploys many of the typical Blumhouse devices. And sure, I had some questions along the way (Why didn’t The Grabber take Finney’s toy rocket ship, an evident weapon?), but the film’s momentum and strong performances neutralized my quibbles. Although Blumhouse offerings from Paranormal Activity to The Purge tend to feel gimmicky and often impersonal, Derrickson adapts Hill with a passion that upgrades the material. We can sense the filmmaker putting himself onto the screen, making The Black Phone feel more than just an average shocker with a good premise and a scary villain.

(Editor’s note: This review was edited to correct a reference from Thames to McGraw.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review