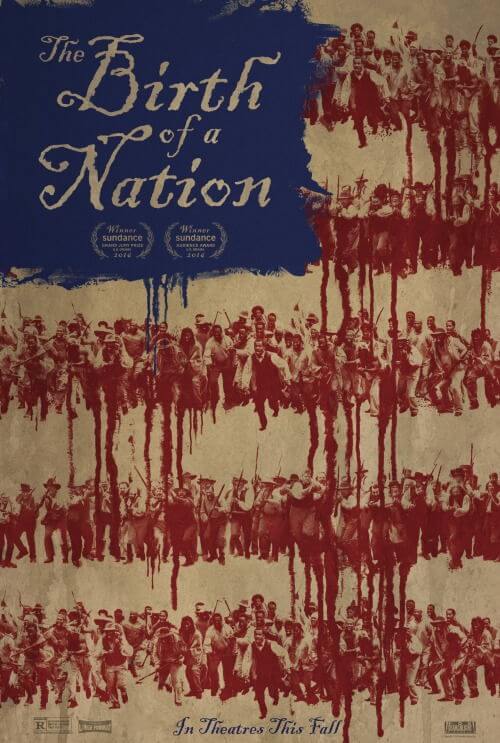

The Birth of a Nation

By Brian Eggert |

Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation tells the story of Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in 1831, commonly known as “Nat’s Fray,” a bloody page from history seldom mentioned in school textbooks. Turner was raised on a Virginia plantation and, being exceptionally bright, he learned to read at a young age, mostly religious texts. By his early twenties, Turner experienced visions and saw heavenly apparitions. He proclaimed himself to be God’s vessel and, believing God instructed him to slay his cruel captors, Turner led a revolt against his owners, and also their wives, children, and infants. And while the uprising presents a complex and important subject worth mining, and Turner himself remains a multifaceted figure, Parker depicts him as a singularly righteous vigilante backed by divine justice and wrath. In a barefaced attempt at mythmaking—for both himself and his character—the first-time filmmaker oversimplifies a complex situation into a revenge-based historical drama.

Serving as producer, director, writer, and starring as Turner, Parker selected the title for his directorial debut as a reaction to D.W. Griffith’s 1915 silent epic of the same name. Griffith’s picture remains notable for its formal innovations but impossible for its narrative aggrandizing of the Klu Klux Klan, not to mention its depiction of African Americans as near-monsters. Parker told Filmmaker magazine at his film’s Sundance debut, “I’ve reclaimed this title and re-purposed it as a tool to challenge racism and white supremacy in America, to inspire a riotous disposition toward any and all injustice in this country.” Parker’s intention proves achingly germane given the last several months in the United States: Protests fed by outrage against questionable police shootings; the existence and apparent necessity for Black Lives Matter; the frightening possibility that a certain presidential candidate, whose outward racism has encouraged an unimaginable community of intolerance in support of his candidacy, could actually be elected. Parker’s film reflects the zeitgeist with eerie and tragic accuracy.

But the conceit of Parker’s approach is that his motivations are not supported by the filmmaking. Choosing such an iconic, yet maligned title with the intention of repurposing it sets up a series of expectations that Parker’s film fails to achieve. After all, Parker’s intention is to wipe out more than one hundred years of associations between Griffin and his rather damnable, highly contentious film. If successful, his accomplishment would place himself among the great first-time filmmakers: Orson Welles, Joel and Ethan Coen, Kenneth Branagh, Spike Jonze, or Steve McQueen. To accomplish this, Parker uses both filmic and religious iconography to bolster his drama. But instead of inspiring his audience, Parker’s desperation to achieve greatness proves transparent, while the quality of filmmaking does not equal his ambitions.

Born into slavery, the young Turner sees a medicine man of sorts, and because of a curious birthmark on his chest, he’s prophesied to be a child of God. As an adult, Turner’s preaching becomes an opportunity for his owner (Armie Hammer), a broke and drunken plantation owner, to tour with Turner around Virginia. Forced to orate troubling biblical messages (“Slaves submit yourselves to your masters with all respect”) to fellow slaves, Turner begins to grasp the brutal extent to which his people have been horrifically oppressed. Finally, with the rape of Turner’s wife, Cherry (Aja Naomi King), and the rape of another woman (Gabrielle Union) married to Turner’s friend (Colman Domingo), Turner resolves to rise up. He waits for a sign from God to make his move, soon interpreting an eclipse as the go-ahead. What ensues in the film’s final third is Turner’s deadly rebellion alongside a small army of men who free themselves from bondage.

From start to finish, Parker gives Turner all the attention, whereas every other character onscreen feels underdeveloped. Most of Turner’s fellow insurrectionists, and the white characters as well, lack personality. Instead, they occupy familiar tropes, having only slight dimensionality. Cherry, for example, is notable only in that she’s pretty and loves Turner. After her rape, she appears cruelly pummeled beyond recognition. Rather than allow the audience to feel empathy, or even granting King a moment to shine in a scene of emotional devastation, Parker makes the moment about Turner’s outrage and hunger for vengeance. Some viewers may draw off-screen parallels about Parker not giving rape victims their due consideration and attention.

As many journalists have reported, Parker consulted Mel Gibson prior to shooting The Birth of a Nation. What becomes evident is how Parker’s script bears similarities to Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) and ends in a way familiar to Braveheart (1995), complete with a tortured hero and an overt use of religious iconography. When Parker shows Turner being whipped for standing up to white slave owners, Turner appears with arms extended, virtually on the cross. After his flagellation, Turner sees an angel of color dressed in white gowns, standing before a shining light and spreading her white, feathery wings. The reverie is meant to evoke awe, but instead, it seems strikingly out of place. When he’s captured after the revolt, Parker is quick to draw parallels between Turner and the angel. One low-angle shot glorifies Turner in his prison cell; a white light floods the frame and silhouettes Turner in an angelic glow.

In the film’s final scenes, Parker skips over the trial that led to Turner’s execution. In real-life, while Turner waited in jail, he was interviewed by wealthy attorney Thomas R. Gray, resulting in the publication of The Confessions of Nat Turner in 1831. This first-person account provides the most complete source of Turner’s insurrection. And yet, Parker rushes Turner to his hanging to transform the figure into a Christ-like martyr. But instead of yelling “Freedom!” like William Wallace, Turner sees yet another welcoming angel. Indeed, Parker saturates The Birth of a Nation with religious imagery that bursts from the subtext to become obvious and overwrought. Meanwhile, he alters the historical reality in questionable ways. Rather than slaughtering entire households, Turner spares women and children, though Turner was far less merciful in reality.

Part of the reason The Birth of a Nation does not achieve its usurping reclamation of its title is because of the production’s budgetary constraints. Shooting on a shoestring budget, Parker barely had the time or money in his month-long schedule to get enough epic-sized coverage, leaving editor Steven Rosenblum without much to work with. Elliot Davis’ gorgeous cinematography captures some beautiful and horrific scenes from the Savannah-based production, but several sequences feel truncated, or at least lacking their full potential for visual breadth. Likewise, some of the acting seems cornball in a made-for-TV way. Hammer, Penelope Ann Miller as the plantation owner’s widow, and Mark Boone Junior playing a corrupt reverend have not quite mastered their southern drawl; whereas Domingo and King barely have enough screentime to make their characters memorable.

Although the significance of Nat Turner’s rebellion remains relevant today, Parker follows a structure well-treaded by Gibson and other filmmakers, leaving this debut with a persistent familiarity and directorial heavy-handedness. Parker’s screenplay lacks characterization for his actors, and his symbolic choices remain unsubtle. We are left feeling that Parker may have achieved what he set out to do had he made a few other films first. However, he’s made a clunky film that invites comparisons to McQueen’s masterful 12 Years a Slave, though it has none of the restraint or artistry. Moreover, Turner was most likely a contradictory person and potentially troubled by mental illness, yet Parker never introduces a skeptic into his drama. The Birth of a Nation resolves to simplify Turner’s life and revolt into a religious parable about Old Testament righteousness and eye-for-an-eye moral justifications. To be sure, the entire production feels a little too self-important, and far less artistic and significant to film history than it aims to be.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review