Reader's Choice

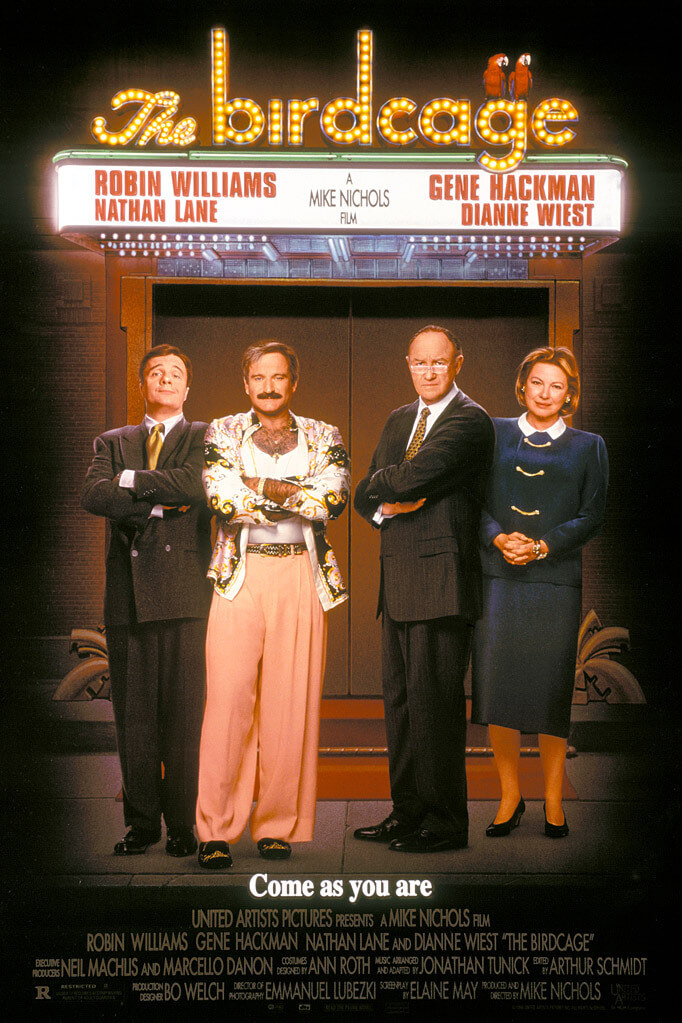

The Birdcage

By Brian Eggert |

At first glance, Mike Nichols’ The Birdcage is pure farce. Robin Williams and Nathan Lane play an openly gay couple who operate a drag club in South Beach, Florida. Their son plans to marry the daughter of a right-wing politician, leading to an outlandish charade when the same-sex couple must perform a straight act for their son’s benefit. Although this comedy of errors supplies an endless stream of laughs and ridiculous situations, it also starts a conversation about the nature of performance in the LGBTQ community—especially among drag queens, who, not unlike the film, explore the boundaries of gender and sexuality in celebration of a larger community. But it’s the need to be accepted, even if one must perform to feel welcome, that resides at the film’s center. And in the years since its debut in 1996, The Birdcage has been seen as a crucial moment in the visibility and acceptance of gay men in cinema, not to mention a comedic investigation into the cultural codes of masculinity. Detractors have questioned the degree to which it perpetuates stereotypes by depicting a flamboyant, non-threatening gay couple to the mainstream public. Defenders see the film’s use of humor as a healing power, which allows viewers to recognize that everyone, regardless of their sexuality or politics, engages in performance. Some dress themselves in a wig, fake eyelashes, and leopard-print attire; others wear a suit and speak in the rhetoric of their political party.

Williams plays Armand Goldman, the Jewish owner of the titular Miami nightclub whose campy cabaret show stars his lover, Albert (Lane). Their relationship consists of Armand calming Albert’s various states of comic mania. When we first meet him, Albert refuses to go on stage, evoking Michael Powell and Emmerich Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) when he announces, “Victoria Page will not dance the dance of the red shoes tonight”—a shrieking prima donna routine that offers the first glimpse at Albert’s many culturally coded feminine behaviors. Before long, and with the help of their Guatemalan “houseboy” named Agadora (Hank Azaria), Armand convinces Albert to take the stage. Downstairs, Albert performs a Sondheim-inflected act for an enthusiastic drag show crowd, comfortable and alive in a way this otherwise crumbling and insecure character rarely appears. Upstairs, in the couple’s apartment above the club, Armand meets with his son, Val (Dan Futterman)—the result of a one-night exploratory tryst with a Katherine (Christine Baranski) some twenty years earlier. It’s an odd scene, one that does not reveal Val’s identity at first, and thus convinces the viewer of Albert’s suspicion that Armand is having an affair with a younger man. After carrying on the illusion that Armand and Val are illicit lovers for a questionable length of time, the film reveals the father-son nature of the relationship.

The Birdcage is filled with unnecessary conflicts such as this, most of which could be resolved with a rational conversation. But what’s the fun in that? Val, it turns out, is getting married to a young woman, Barbara Keeley (Calista Flockhart), whose fanatical right-wing parents will doubtless refuse the match if they discover that Val’s parents are two men. And so, at the behest of his son, Armand begrudgingly agrees to pass himself off as “normal” and host a dinner party to convince the future in-laws of Val’s good stock. The boy’s long-lost mother, Katherine, even agrees to finally meet her son and complete the illusion of a traditional family. Meanwhile, Armand and Val tell Albert, “It would be better if you weren’t here.” After all, Albert cannot change his mannerisms and suppress his identity, no matter how much he tries to walk like John Wayne. But even though they remove any conspicuous decorations or signifiers—leaving their apartment all but empty except for a newly added crucifix that, along with the stone walls, makes the space look downright monastic—their attempt to appear straight accentuates what they try to conceal. Albert’s impromptu solution entails donning a wig and performing as Armand’s wife.

The Birdcage is filled with unnecessary conflicts such as this, most of which could be resolved with a rational conversation. But what’s the fun in that? Val, it turns out, is getting married to a young woman, Barbara Keeley (Calista Flockhart), whose fanatical right-wing parents will doubtless refuse the match if they discover that Val’s parents are two men. And so, at the behest of his son, Armand begrudgingly agrees to pass himself off as “normal” and host a dinner party to convince the future in-laws of Val’s good stock. The boy’s long-lost mother, Katherine, even agrees to finally meet her son and complete the illusion of a traditional family. Meanwhile, Armand and Val tell Albert, “It would be better if you weren’t here.” After all, Albert cannot change his mannerisms and suppress his identity, no matter how much he tries to walk like John Wayne. But even though they remove any conspicuous decorations or signifiers—leaving their apartment all but empty except for a newly added crucifix that, along with the stone walls, makes the space look downright monastic—their attempt to appear straight accentuates what they try to conceal. Albert’s impromptu solution entails donning a wig and performing as Armand’s wife.

Of course, the fact that Val asks his parents to disguise themselves speaks to the rather unlikable character’s insensitivity, which escalates when he pouts that “this is never going to work” in the moments before the Keeleys arrive. It’s all the more wounding because Val’s attempt at marriage represents something Albert and Armand cannot have in 1996; to legally validate their partnership, they rely on a palimony agreement, designed for unmarried, live-in relationships. Val remains oblivious, while Armand is cast with a touch of sadness as he deliberates over what his son will have that he cannot. It’s a rare, delicate moment between them when Armand gives Albert a palimony document to sign. But The Birdcage is far from a tragedy, even though 1990s movies frequently portrayed LGBTQ characters in a humanizing but tragic light, often paired with the theme of AIDS. The mainstream examples range from Philadelphia (1993) to Jeffrey (1995)—films that deal with the problems of queer characters. A few essential LGBTQ love affairs found their way onto the arthouse circuit at the time, including My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), Desert Hearts (1986), and My Own Private Idaho (1991). And the “gay best friend” became a trope in romantic comedies with Steve Zahn in Reality Bites (1994), Simon Callow in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), and Rupert Everett in My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997). But The Birdcage has been described as the first comedy about queer characters not weighed down by serious themes; however, they reside just under the surface.

The source material goes back to a French play written by Jean Poiret, first performed in 1973. Édouard Molinaro based his 1978 film, La Cage aux Folles, on Poiret’s play, and delivered an unexpected international hit. The French farce, filled with over-the-top performances and taboo subject matter (in the United States), earned three Oscar nominations (Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Costume Design) and spawned two sequels in 1980 and 1985. It also inspired Harvey Fierstein’s Tony-winning musical from 1983, with music and lyrics by Jerry Hermann, and had two celebrated revivals. The idea had transitioned from stage to film, back to the stage, and then to film again with The Birdcage. The Hollywood version, distributed by United Artists, reunited its director, Mike Nichols, with his former partner, Elaine May, who penned the adaptation. Nicholas and May had started out together in the 1950s as an improvisational duo whose Broadway show and three best-selling albums made them comedy icons. Nichols, an EGOT winner, had since directed stage productions and made some essential films like The Graduate (1967), Carnal Knowledge (1971), and Working Girl (1988), but he experienced a commercial downturn in the 1990s. May had also directed several features, but her highly publicized flop with Ishtar (1987) left her labeled as box-office poison. The Birdcage marked a comeback for both.

Given the material’s long and celebrated history, it’s not surprising that Nichols’ film earned nearly $125 million in domestic box-office receipts. But it’s an incredible feat given that, just ten years earlier, the 1980s were marred by the AIDS pandemic, rampant homophobia, and violence against the LGBTQ community. The world had begun to change; exposure to LGBTQ perspectives were becoming more prevalent all the time. Yet, there was still a considerable resistance in conservative America. In 1996, President Bill Clinton, despite his objections, signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) into law, which allowed states the right to refuse the legal union of same-sex marriages. The law, introduced by members of the Republican party in 1996, was deemed unconstitutional some twenty years later. But at the time, the issue had been an active topic among many conservative politicians and media commentators, who raised questions about same-sex marriages in conjunction with matters of morality. They felt traditional family values were under attack by same-sex marriages, and so, under the law, members of the LGBTQ community were relegated sub-citizens without the same rights afforded to others. Nicholas and May openly address the political and cultural division in the United States with The Birdcage, reflecting the sociopolitical rhetoric of the mid-1990s in the dialogue and character descriptions.

Given the material’s long and celebrated history, it’s not surprising that Nichols’ film earned nearly $125 million in domestic box-office receipts. But it’s an incredible feat given that, just ten years earlier, the 1980s were marred by the AIDS pandemic, rampant homophobia, and violence against the LGBTQ community. The world had begun to change; exposure to LGBTQ perspectives were becoming more prevalent all the time. Yet, there was still a considerable resistance in conservative America. In 1996, President Bill Clinton, despite his objections, signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) into law, which allowed states the right to refuse the legal union of same-sex marriages. The law, introduced by members of the Republican party in 1996, was deemed unconstitutional some twenty years later. But at the time, the issue had been an active topic among many conservative politicians and media commentators, who raised questions about same-sex marriages in conjunction with matters of morality. They felt traditional family values were under attack by same-sex marriages, and so, under the law, members of the LGBTQ community were relegated sub-citizens without the same rights afforded to others. Nicholas and May openly address the political and cultural division in the United States with The Birdcage, reflecting the sociopolitical rhetoric of the mid-1990s in the dialogue and character descriptions.

The Birdcage also received accolades for bringing queer characters and drag queens to mainstream Hollywood. While the 1990s started to normalize drag culture on film, or attempt to anyway, Jennie Livingston’s documentary Paris is Burning was the first to raise considerable awareness about drag queens onscreen. Her film about drag balls captures the defiance of opposing attitudes that becomes so essential in its spectacle, whereas the drag queen movies that immediately followed seemed less authentic—rooted in the same impulse that made Some Like it Hot (1959) or Tootsie (1982) funny. The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994) and To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar (1995) certainly explored the world of drag queens and made spending time with these characters enjoyable for unacquainted viewers, marking important moments in LGBTQ representation. But they tend to have a streak of laughing at their subjects, even as they drive our empathy. Then again, May’s screenplay for The Birdcage tends to turn everyone into the butt of a joke, apart from the bland Val and Barbara, who lack any chemistry thanks to dull roles performed by Futterman and Flockhart.

Indeed, May’s witty screenplay shreds the Keeleys, who represent the “normal” right-wing position. True to May’s brand of comedy, she takes aim at WASPs and portrays them as absurd, hypocritical characters. Senator Kevin Keeley (Gene Hackman), the Christian-valued co-founder of the “Coalition for Moral Order” committee, believes that Billy Graham is too liberal and treats his wife Louise (Dianne Wiest) like a doormat. With an election looming, The Senator faces a scandal when his trusted colleague and committee co-founder dies in bed with “an underage black whore.” But he sees his daughter’s wedding as an opportunity to counteract the negative press and reinforce his position on family values. And so, Barbara feels she has no choice but to lie when her father asks about Val’s parents, hiding not only that they are gay men but also Jewish—requiring Armand and Albert to adopt the persona of straight, god-fearing Americans who take the name “Coldman” (“the ‘d’ is silent”). May’s barbed treatment of Senator Keeley comes in subtle jabs, including an overindulgence of sweets and a self-obsession that includes watching his own appearance on a right-wing talk show—reminiscent of The McGlaughlin Group, complete with pundits shouting over each other (“It’s the most intelligent show on television,” he insists). Other jabs are not so subtle, ranging from racism to American exceptionalism, besides the obvious homophobia. At the eventual dinner party, the Keeleys refer to Agador as a “beige savage,” condemn Armand’s “European snobbery,” and soapbox against gays in the military. Later, when the Senator is drawn to Albert’s caricature of a conservative woman (who preaches that “if you stop the doctors, you stop the abortions”), May seems to say that only an absurd person could take an outlandish caricature seriously.

Even while mocking the Keeleys’ conservatism, The Birdcage embraces stereotypes and frequently uses its gay characters as comedic devices, even while it weaves a place for them into the fabric of American culture. Although the remake improves upon the arthouse original, which also poked fun at its protagonists (Owen Glieberman described it as “a gay minstrel show”), Nichols puts a sympathetic same-sex couple the center of a major Hollywood production for the first time. Still, looking back today, certain aspects of the remake that seemed elevated in 1996 could be accused of perpetuating negative clichés. Lane’s effeminate, pastel-wearing, limp-wristed, and flamboyant behavior has been described as a damaging representation. But every time Lane’s ostentatious outfits, effeminized cackle, or skewed conception of heterosexual performance earn a hearty laugh, they also endear the audience to his behavior and promote acceptance. The film also presents Armand and Albert in terms of gender binarism, with Armand has the husband and Albert as the wife, a model that suggests a couple requires both masculine and feminine components. Armand and Albert, too, have been framed against the “normal” American family, the Keeleys, which offers them as an alternative lifestyle rather than an acceptable norm. Even though they have a place in the fabric of America, The Birdcage reinforces their place on the margins.

Even while mocking the Keeleys’ conservatism, The Birdcage embraces stereotypes and frequently uses its gay characters as comedic devices, even while it weaves a place for them into the fabric of American culture. Although the remake improves upon the arthouse original, which also poked fun at its protagonists (Owen Glieberman described it as “a gay minstrel show”), Nichols puts a sympathetic same-sex couple the center of a major Hollywood production for the first time. Still, looking back today, certain aspects of the remake that seemed elevated in 1996 could be accused of perpetuating negative clichés. Lane’s effeminate, pastel-wearing, limp-wristed, and flamboyant behavior has been described as a damaging representation. But every time Lane’s ostentatious outfits, effeminized cackle, or skewed conception of heterosexual performance earn a hearty laugh, they also endear the audience to his behavior and promote acceptance. The film also presents Armand and Albert in terms of gender binarism, with Armand has the husband and Albert as the wife, a model that suggests a couple requires both masculine and feminine components. Armand and Albert, too, have been framed against the “normal” American family, the Keeleys, which offers them as an alternative lifestyle rather than an acceptable norm. Even though they have a place in the fabric of America, The Birdcage reinforces their place on the margins.

Then again, given the political climate in the United States in 1996, The Birdcage represents a step in the right direction and does far more good than harm. Doubtless, it introduced a certain segment of the otherwise unfamiliar mainstream audience to queer culture by virtue of Williams’ celebrity alone. And the film’s central theme, pronounced by Sister Sledge’s “We Are Family” played in bookend scenes, offers hope for acceptance, or at least tolerance, of different cultural and social bubbles. To be sure, the film’s traditionally oppositional groups—left and right, gay and straight, Jewish and Christian—come together in an impossible and simplistic, yet also cleverly symbolic finale. Having had enough farce for one evening, Val confesses everything to the Keeleys. And to help the Senator escape the press snooping outside of their apartment, Armand and Albert dress the Keeleys in drag costumes that allow them to flee. The Senator’s fear of exposure requires him to perform in costume, which, in effect, allows him a brief sense of the queer experience in America in the 1990s—the fear and embarrassment that comes from the performative necessity in some situations to “act normal” for a disapproving public. The ruse works: the Keeleys flee the scene and avoid detection, and given the final images of Val and Barbara’s wedding, presided over by a priest and rabbi, they have approved the marriage and accepted non-traditionalism into their family. The two families sit on opposite sides of the aisle, the gray and dour conservatives appropriately situated on the right, the pink and expressive LGBTQ community on the left. But they’re also joined together.

The Birdcage is a hopeful and riotous film, and it would be a mistake not to recognize the outrageous comic performances by Williams and Lane, while Hackman and Wiest deliver a somewhat subtler form of humor, though no less caricatured. The sheer volume of laughs leaves it possible to watch their work and not feel the film preaching at you. Except, for all the comedy’s lasting humor, it becomes more relevant every day. Although the U.S. government has made progress in the decades since the film’s release, such as legalizing same-sex marriage, the country’s swing toward the right also makes the film a fantasy. Senator Keeley was an intentionally cartoonish exaggeration at the time, but his remarks that “people in this country don’t trust details, they trust headlines” and “morality is political” reveal that our society has taken a step back toward this film’s hyperbolic world of 1996. We now must wonder: If The Birdcage were made today, would the same thing happen? Is our society, driven to the brink of partisan politics and ideological division, mature enough to enjoy The Birdcage on both sides of the aisle? The depressing answers to these questions make the film a nostalgic encapsulation of a time that, despite the progress in LGBTQ representation and visibility, also seems tragically simpler.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Dustin!)

Bibliography:

Stevens, Kyle. Mike Nichols: Sex, Language, and the Reinvention of Psychological Realism. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Whitehead, J.W. Mike Nichols and the Cinema of Transformation. McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review