The Bikeriders

By Brian Eggert |

The Bikeriders, the latest engrossing film by writer-director Jeff Nichols, who hasn’t released a new feature since 2016, reminds moviegoers what they’ve been missing. Nichols based his complex and violent film on the 1968 book by Danny Lyon, a photojournalist who, in the spirit of Hunter S. Thompson’s book about the Hell’s Angels, spent years with an outlaw motorcycle club as research. Following Lyon’s text, Nichols takes us into a secret masculine world, complete with its desire for freedom, possessiveness, violence, and borderline ritualistic need for order—qualities that often contradict each other and, in time, corrupt the overarching institution. Nichols’ lens through which he looks at this world is Kathy, played in an outstanding performance by Jodie Comer. Kathy is the wife of a member of the fictionalized Vandals, based on Chicago’s Outlaws Motorcycle Club. Through her account, The Bikeriders is an almost ethnographic study of a niche group whose romantic prime was short-lived and, like so many other American institutions in this era, corrupted by the influence of power and greed, and then ruined by battles for control. If Nichols occasionally softens the real-life edges in this otherwise brutal film, he captures the attractive yet repulsive dynamic that makes his subject fascinating.

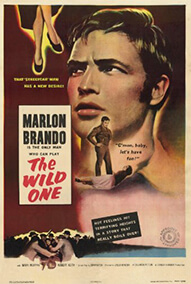

Early in the film, Kathy explains that Johnny, played by Tom Hardy in another of his idiosyncratic performances, started the club after watching a television broadcast of The Wild One (1953). In an iconic scene from that film, a character asks Marlon Brando’s biker, also named Johnny, what he’s rebelling against. “Whaddya got?” Brando replies. With that, Hardy’s character wants to lead a biker gang, and the Vandals are born. Although motorcycle clubs existed before The Wild One, they surged in the post-World War II era as a bastion for veterans at odds with reintegrating into American society. Motorcycle enthusiasts could escape domesticity, embrace the freedom of the open road, and maintain a sense of control over their lives. The Wild One’s imagery may have been appropriated later in LGBTQ+ and BDSM circles, but it, along with Easy Rider (1969), helped romanticize outlaw motorcycle clubs. The reality, as Johnny learns later in the film, is that these clubs would take on a life of their own, devolving from the idyllic spirit of American freedom into a source of corruption and criminality. Their trajectory mirrors that of mobsters from this era, which, with the integration of drugs and gangs competing for power, went from a respectable form of nonconformity to a malicious force.

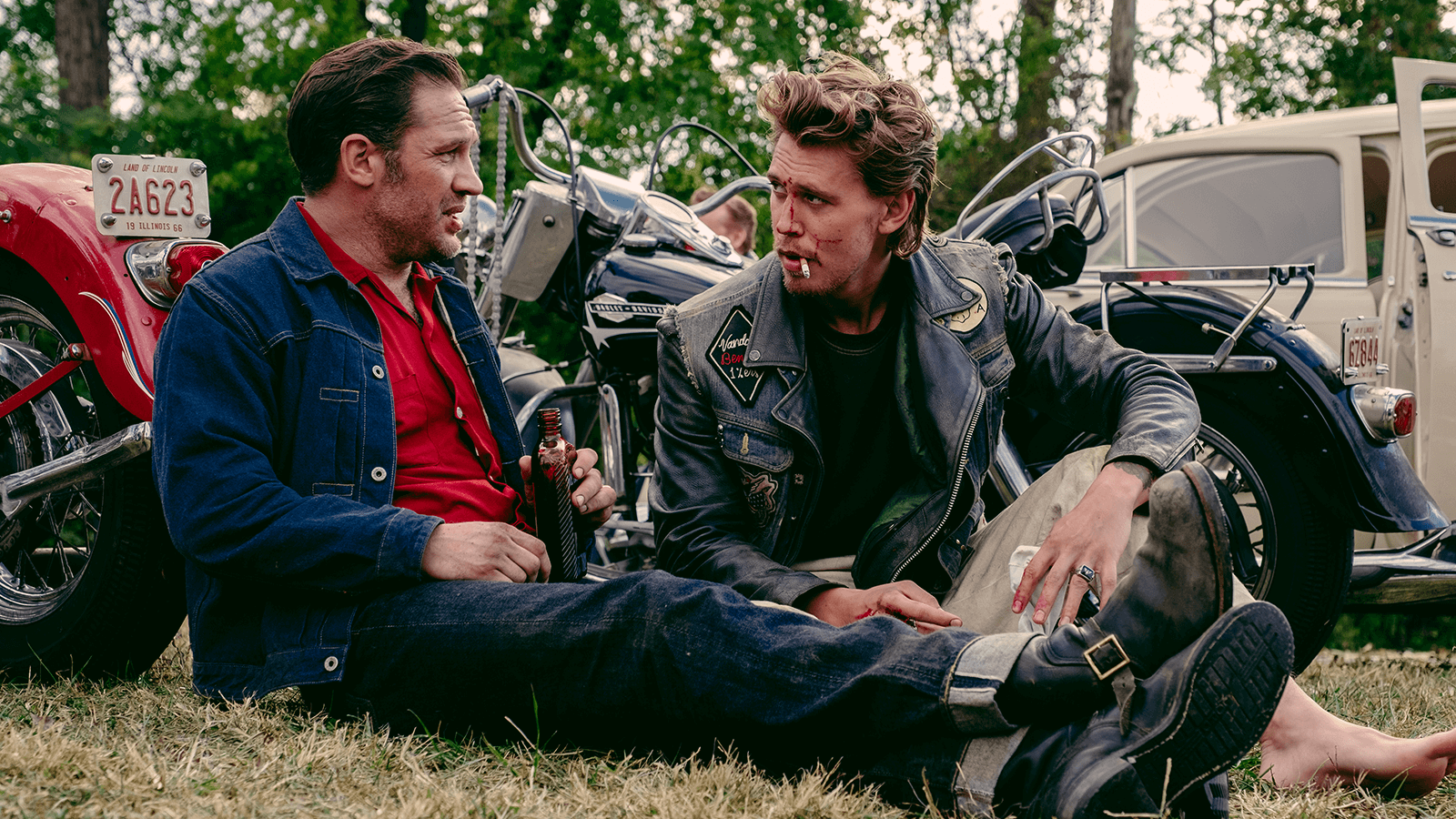

How appropriate, then, that Nichols’ treatment of the story recalls another gangster film, Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990), in its narrative structure and use of voiceover. But instead of its protagonist reflecting on his personal experiences as a gangster, or, in this case, a biker, the story is told by Kathy, a constant voice of critique. In a series of interviews conducted by Lyon (Mike Faist), Kathy both explains and remarks on the Vandals, the key players therein, and the downfall of Johnny’s regime. One scene where she lists the members of Johnny’s Chicago chapter of the Vandals plays like Henry Hill from Goodfellas listing his wiseguy compatriots in The Bamboo Lounge. There’s Johnny’s loyal right-hand Brucie (Damon Herriman); the gearhead Cal (Boyd Holbrook); the unstable reject Zipco (Michael Shannon); the bug-eating Cockroach (Emory Cohen); the seedy California convert Funny Sonny (Norman Reedus); and friends Corky (Karl Glusman) and Wahoo (Beau Knapp). But none of them quite has the rebel-without-a-cause persona down better than Benny (Austin Butler), Kathy’s husband and Johnny’s favorite to replace him. Benny needs freedom more than any of the others, and when the club begins its downward spiral, perhaps no one else feels more betrayed.

How appropriate, then, that Nichols’ treatment of the story recalls another gangster film, Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990), in its narrative structure and use of voiceover. But instead of its protagonist reflecting on his personal experiences as a gangster, or, in this case, a biker, the story is told by Kathy, a constant voice of critique. In a series of interviews conducted by Lyon (Mike Faist), Kathy both explains and remarks on the Vandals, the key players therein, and the downfall of Johnny’s regime. One scene where she lists the members of Johnny’s Chicago chapter of the Vandals plays like Henry Hill from Goodfellas listing his wiseguy compatriots in The Bamboo Lounge. There’s Johnny’s loyal right-hand Brucie (Damon Herriman); the gearhead Cal (Boyd Holbrook); the unstable reject Zipco (Michael Shannon); the bug-eating Cockroach (Emory Cohen); the seedy California convert Funny Sonny (Norman Reedus); and friends Corky (Karl Glusman) and Wahoo (Beau Knapp). But none of them quite has the rebel-without-a-cause persona down better than Benny (Austin Butler), Kathy’s husband and Johnny’s favorite to replace him. Benny needs freedom more than any of the others, and when the club begins its downward spiral, perhaps no one else feels more betrayed.

Still, Kathy’s voiceover is not a consistent framing device, since Lyon often interviews other members of the gang, which explains some—but not all—scenes that occur outside of Kathy’s or even Lyon’s purview. However, the influence of Scorsese’s film is unmistakable, from the violent opener to how Nichols portrays the gradual decline of the Vandals’ heyday, overcome by an element that no longer respects the foundational motivations of the club. For another gangster movie comparison, namely Carlito’s Way (1993) analogy, Johnny stands as a past-his-prime Carlito Brigante, who’s challenged by younger, more unruly competition—the resident Benny Blanco from the Bronx, represented by The Kid (Toby Wallace), a raggedy youth who wants to join the Vandals. To be sure, like many gangster films set during this era, The Bikeriders charts a familiar decline of American institutions during the 1960s and 1970s, where, in the wake of the Kennedy assassination, the senseless Vietnam War, and political corruption in the Nixon administration, all innocence was lost—even the relative innocence of mobsters and biker gangs. Moreover, no doubt hoping to keep the characters relatable, Nichols omits many of the vilest aspects of these clubs, such as dabbling in white supremacy and various forms of trafficking (drugs, weapons, human).

Nichols’ film is filled with characters who start by carving out their place in the world, and within a few short years, they no longer have a place in the club they helped launch. But for a while, one can understand what’s so attractive about the group. The Vandals ride on highways in skein formation, with Johnny as the lead goose. Their camaraderie means they can fight to resolve their differences but still have a beer and a laugh afterward. Brucie remarks at one point, “These guys don’t belong nowhere else, so they belong together.” And when someone wants to challenge Johnny’s authority—and anyone can—he asks them, “Fists or knives?” Should he lose, someone else could take over his post as gang head.

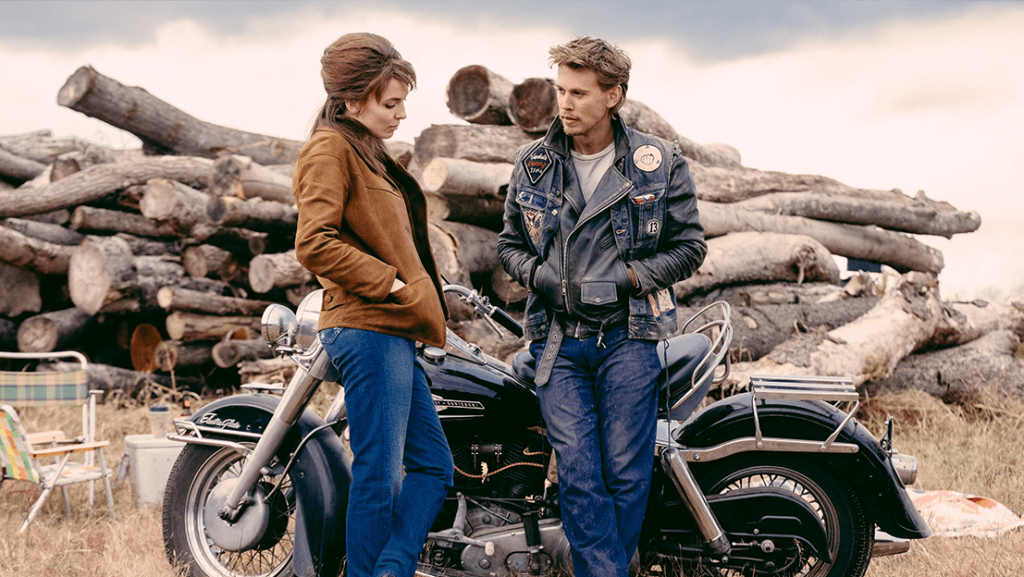

More even than challengers, it’s the fragile love triangle between Kathy, Benny, and Johnny that disrupts the gang. After Benny is brutally injured, nearly losing his foot in an attack by goons who had a problem with the Vandals’ insignia, Johnny unleashes hell. While his Vandals burn down the bar where Benny was attacked, firefighters and cops stand by, and Johnny gets a sense of his power. Power corrupts him, but so does his obsession with Benny’s freewheeling spirit. Even so, Kathy wants to keep her husband safe. She goes to Johnny and tells him that he can’t have Benny. “He’s mine,” she declares. But Benny, with his James Dean streak of rebellion, refuses to be tied down by anyone—neither Kathy nor Johnny.

Captured in blazing, sun-drenched light by cinematographer Adam Stone with dingy interiors by production designer Chad Keith, The Bikeriders boasts a polished aesthetic reminiscent of Nichols’ other Southern Gothic features, including Shotgun Stories (2007), Take Shelter (2011), Mud (2012), and his two 2016 releases, Midnight Special and Loving. Since then, Nichols has been busy developing several projects, including a relaunch of Alien Nation, that have fizzled out. However, the filmmaker’s commitment to writing and directing his own projects, as opposed to embracing a one-for-them, one-for-me model, or selling out altogether to make a franchise movie, remains refreshing. Nonetheless, his latest film earns its authenticity from the performances, with well-known actors such as Hardy, Butler, Shannon, and Reedus embodying their roles. The standout, of course, is Comer, whose showy Chicago accent and anchoring performance guides the viewer through this masculine world with equal measures of fascination and mistrust of its declared ideals. The Killing Eve (2018-2022) and The Last Duel (2021) star centers the story and ensures that the viewer never gets too swept up in the Vandals’ appeal—that we always watch with a slight skepticism.

Captured in blazing, sun-drenched light by cinematographer Adam Stone with dingy interiors by production designer Chad Keith, The Bikeriders boasts a polished aesthetic reminiscent of Nichols’ other Southern Gothic features, including Shotgun Stories (2007), Take Shelter (2011), Mud (2012), and his two 2016 releases, Midnight Special and Loving. Since then, Nichols has been busy developing several projects, including a relaunch of Alien Nation, that have fizzled out. However, the filmmaker’s commitment to writing and directing his own projects, as opposed to embracing a one-for-them, one-for-me model, or selling out altogether to make a franchise movie, remains refreshing. Nonetheless, his latest film earns its authenticity from the performances, with well-known actors such as Hardy, Butler, Shannon, and Reedus embodying their roles. The standout, of course, is Comer, whose showy Chicago accent and anchoring performance guides the viewer through this masculine world with equal measures of fascination and mistrust of its declared ideals. The Killing Eve (2018-2022) and The Last Duel (2021) star centers the story and ensures that the viewer never gets too swept up in the Vandals’ appeal—that we always watch with a slight skepticism.

The Bikeriders has a transportive effect, similar to Goodfellas, where the film drops us into a specific subculture and dissects it from the inside out. Although not without its apprehensions about this rowdy lifestyle and, later, lament over how monstrous these clubs would become, there’s a sense of melancholy in watching the heyday devolve and lose its sense of purpose. But what can you do? “You can give everything you got to a thing—all you got,” observes Johnny. “And it’s still gonna do what it’s gonna do.” Like Easy Rider and many examples in the gangster genre, Nichols’ film acknowledges both what draws people to such groups while assessing their gradual degradation as not only a loss but a symptom of a greater condition of mid-twentieth-century America. This is an engrossing, thoughtfully made film, packed with terrific performances and an immersive sense of time and place. Its summer release from Focus Features risks the film getting lost among blockbuster programming, but its sheer star power may attract audiences. Regardless, The Bikeriders is another terrific entry in Nichols’ career, and hopefully, we won’t have to wait so long until his next feature.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review