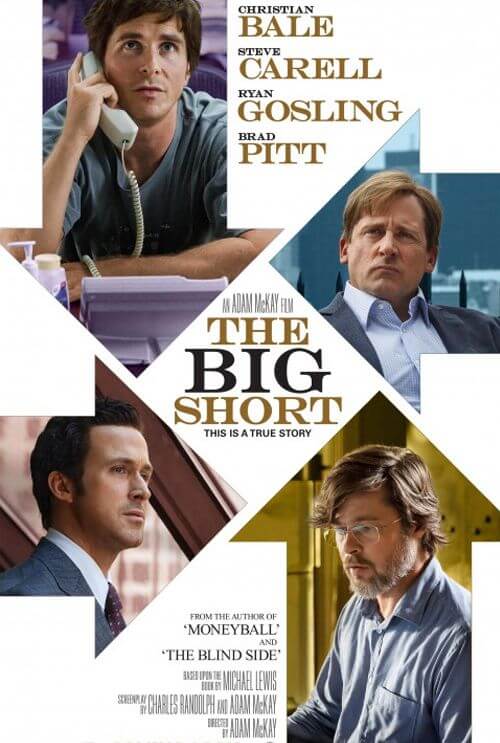

The Big Short

By Brian Eggert |

Trying to understand the 2008 financial collapse, the worst crash since the Great Depression, might take countless diagrams and a vast understanding of housing and money markets, as well as the global economy. Most Americans probably don’t grasp the ins and outs of what happened and why. They had more important things to deal with at the time, such as worrying about their own finances, job, and mortgage. The Big Short attempts to explain what happened, relying on an incredible cast of actors and its playful sense of humor to appeal to the layman. Obviously influenced by Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), director Adam McKay takes a similar approach by delivering a pseudo-comedy to support the otherwise dry subject of sub-prime mortgages, corrupt regulators, and fraudulent banking practices.

Author of Moneyball, Michael Lewis wrote his bestselling book The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine in 2010, bringing his detailed yet straightforward style to a story about those who predicted the rupture of the housing bubble and profited from it. McKay and Charles Randolph adapted the material for their screenplay, omitting a few central characters and reformatting the text into a punchy, post-modern music-video-of-a-film. From its Fourth Wall-breaking characters to its oddball use of intentionally bad makeup for its actors (silly wigs, hairdos, dye jobs, beards, color contacts, etc.), McKay somehow makes an impenetrable subject accessible. Whereas the topic has been handled with more grace in J.C. Chandor’s Oscar-nominated Margin Call (2011), or even Oliver Stone’s Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010), McKay’s defiant treatment just barely avoids becoming so irreverent that its sense of humor overshadows its significance.

Michael Burry (Christian Bale) was the first to notice some questionable numbers in the housing market that supported the national and international economy. A former neurologist with a glass eye and Asperger’s syndrome, Burry analyzes stocks for his hedge fund, Scion Capital; however, after looking through thousands of mortgages, he predicts the crash before anyone else. Investing hundreds of millions in a short, he creates an unheard-of bet against the housing market with something called a credit default swap, which suggested Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) would fail—essentially, Burry discovered the system of CDOs and mortgage-backed security was based on mortgages that were bad (ever increasing in their default rate). Burry’s skeptical investors try everything to get their money back on a seemingly insane theory, but he has full approval to use their money as he sees fit.

Other players in the financial sector catch wind of Burry’s curious move and decide to follow him. Deutsche Bank trader and unapologetic profiteer Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling) races to set up similar swaps and earn himself a pretty commission by bringing the deal to hedge fund manager Steve Eisman (Steve Carell, excellent). Eisman, a cynical and truth-seeking banker who believes everything is corrupt, puts his team (Hamish Linklater, Rafe Spall and Jeremy Strong) on the credit default swap plan, and they validate its authenticity. Though he already believed the system was crooked, Eisman is shocked to discover just how dishonest and fraudulent it proves to be. Meanwhile, a pair of young investors (Finn Wittrock and John Magaro) seek the help of a former banker (Brad Pitt), who has since dropped out of the game from a combination of paranoia and disenchantment, to take advantage of the credit default swap movement. The film carries on as these characters watch the market slowly tumble, and the corrupt banks cover up their losses, until the impending crash cannot be ignored once Lehman Brothers shuts down.

Structurally, The Big Short is consistent only in its inconsistencies. For example, Vennett opens the film and periodically narrates the proceedings by looking straight into the camera, not unlike Leonardo DiCaprio’s character in The Wolf of Wall Street. But the film’s voice also uses titles and typed-out definitions on the screen to communicate significant information; the last minute of screentime is dedicated to such titles, making us wonder what happened to Vennett’s narration. Then there’s the hack-and-slash job done by editor Hank Corwin, who cuts like he’s assembling a Michael Bay movie. Corwin volleys between multiple angles for dialogue-driven office scenes; likewise, cinematographer Barry Ackroyd’s camera movements never cease and the effect proves downright distracting. The film’s overall restlessness feels contrived and forced, as though it’s trying to capture the same energy that fuelled Scorsese’s film, but doesn’t.

To call McKay’s approach broad is an understatement. In one brief scene, Melissa Leo appears as a Standard & Poor’s 500 analyst with an eye condition, an obvious metaphor (Get it? She can’t, or refuses to, see the corruption before her eyes.). Elsewhere, McKay has fun explaining complex issues: When the topic of CDOs first arises, our narrator defers to “Margot Robbie in a bathtub”—and sure enough, there she is, Margot Robbie (who also starred in The Wolf of Wall Street) in a bubble bath, drinking champagne, and explaining CDOs. Anthony Bourdain and Selena Gomez also appear as themselves in funny asides that break down head-scratching financial concepts. At other times, Vennett fully admits that this or that scene has been dramatized for effect, and then proceeds to explain, verbally, how it really went down. (Why not just show the actual events in the first place? Because it’s more fun this way.) Such satirical, comic ticks keep the viewer interested in what ultimately comes down to a bunch of rich white men playing the system to make money.

McKay’s likable cast and the film’s overall levity about the situation may seem flippant, but fortunately, a sense of indignation also pulses through the film’s veins. The Big Short is a lively film that will ultimately attract a large fanbase, if only because the cast remains an impressive ensemble and there are plenty laughs to be had. Where else outside of an Ocean’s film can you see such a group of talents like Bale, Gosling, Pitt, and Carell having such a lark in their semi-comic, semi-serious roles? Because of McKay’s humorous tone and the affable cast, the otherwise sobering topic becomes energizing, and the two-hour-and-ten-minute runtime breezes by. And though its craft and structure lack a strict regularity or cohesion, the film’s contagious feelings of outrage reinvigorates our own rage over the situation. Nevertheless, it’s important to remember that the characters here aren’t admirable folks, despite how conflicted they feel about making hundreds of millions off the crash of the world economy.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review