The Beta Test

By Brian Eggert |

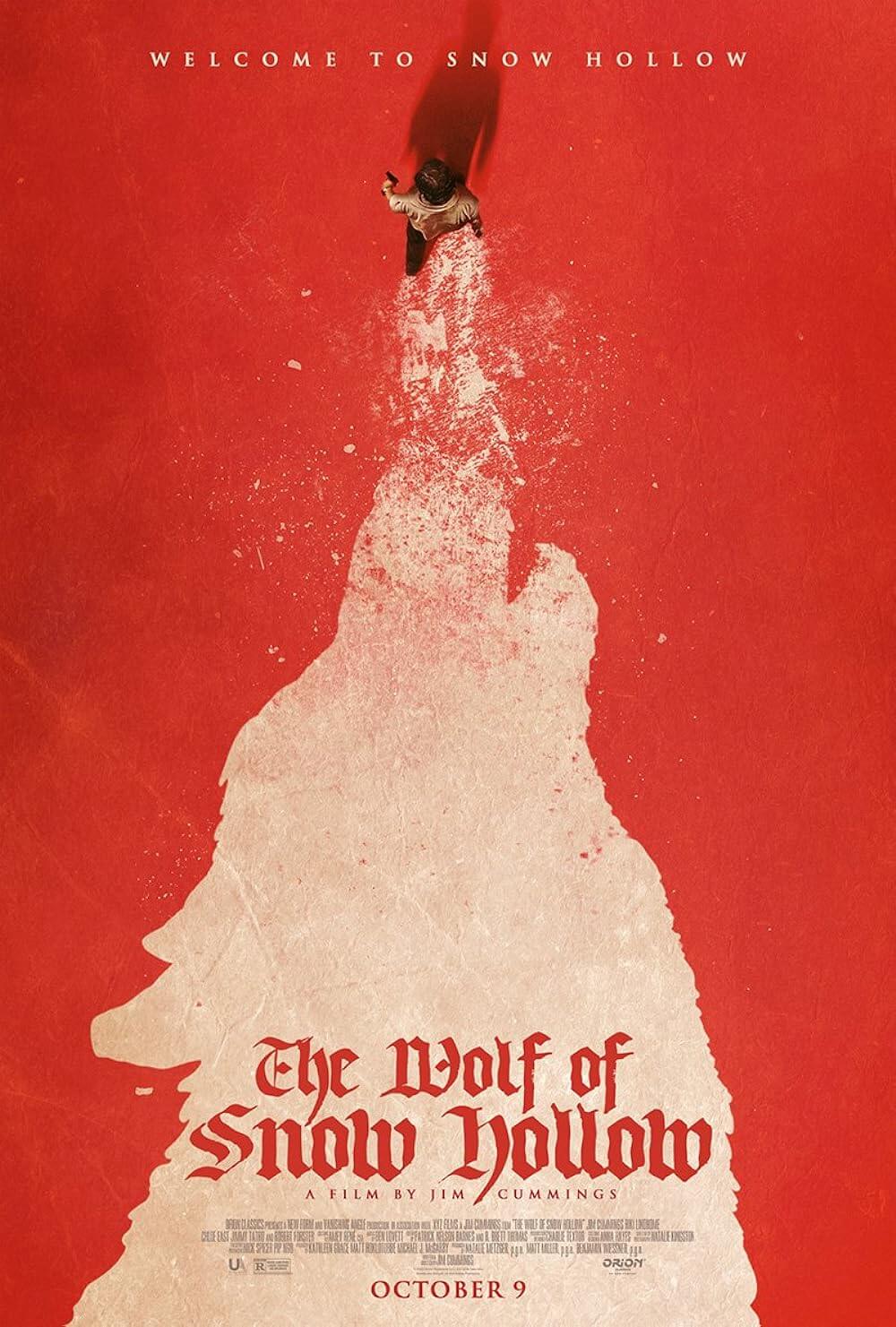

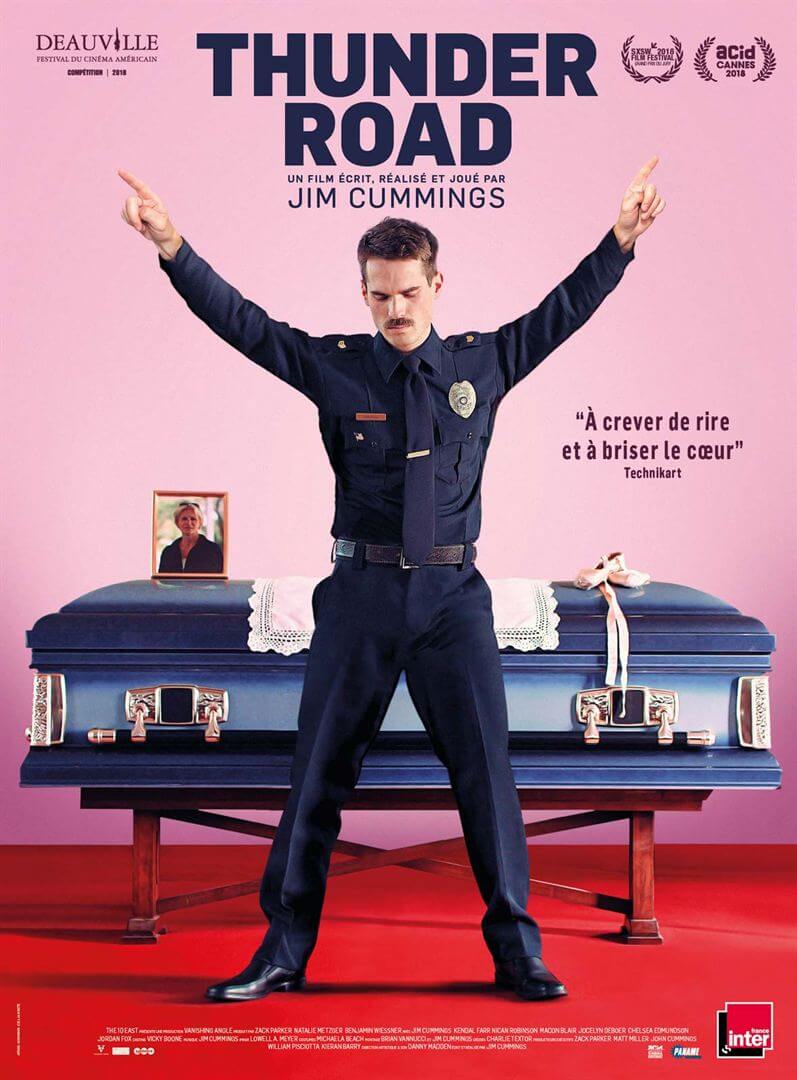

“Image is everything” is the central theme of Jim Cummings and PJ McCabe’s The Beta Test, an independent production that weighs social transparency in the Digital Age, the emptiness of Hollywood dealmakers, and the destructive nature of conformity. This disorienting panic-attack-of-a-movie follows Cummings in another nervous breakdown role, similar to his memorable turns as beleaguered cops in his breakout Thunder Road (2018) and sophomore effort, The Wolf of Snow Hollow (2020). Sharing directing duties and screenplay credit, Cummings and McCabe open their grim satire with a tense murder, transition into post-Harvey Weinstein era Hollywood satire, and end with a sweeping digital data conspiracy. If the throughline isn’t immediately apparent, the same feels true of the film. But in another frantically watchable performance, Cummings pulls us through a gauntlet of unpredictable plotting that doesn’t always result in cohesive storytelling. Yet, it delivers a nervy portrait of how the world’s increasing accountability has become a judgmental nightmare for some, who would be better off just talking about their problems.

Cummings plays Jordan, a wheeling-and-dealing Hollywood agent who’s projecting more success than he could ever handle. A recovering alcoholic who has stopped smoking and can’t drink coffee because of his ulcer, Jordan is full of positive, hollow statements—he greets you with “There he is!” and injects “That’s exciting” and “Let’s keep talking” into every conversation. Other film critics have called him “remorseless” or compared him to Patrick Bateman, but I don’t think that’s accurate. Jordan isn’t a good person (he lies, insults his staff, loses his temper, and abuses his power), but he isn’t a psychopath either. He’s just so used to being “on” that he can’t shut it off anymore. So he’s filled with guilt and shame, and it’s eating away at him because he refuses to acknowledge that his inner life and outer life are out of alignment. Deep in denial about himself and his success, he claims to own that Tesla he leases and buys $10,000 paintings he cannot afford. In a perfect metaphor, his teeth have started to rot because of his overuse of whitening strips. It’s all to maintain his image—even with his fiancée Caroline (Virginia Newcomb), with whom he’s incapable of being honest about his anxieties and sexual proclivities, yet he plans to marry her in a few weeks.

Given that he’s opposed to honesty, Jordan could not possibly tell Caroline that he has fantasies about other women and desires that she doesn’t fulfill. So instead, he daydreams about a blonde woman he sees at a restaurant—they stand up and grunt like animals about to mount each other until the other restaurant patrons begin to shoot video with their smartphones. Suddenly embarrassed by the exposure of his basest impulses, Jordan snaps out of his dream. All of these hangups come to a head when, early in The Beta Test, Jordan receives an anonymous invitation in a purple envelope in his apartment mailbox, offering a “no strings attached” sexual encounter with a stranger. Inside, a card asks for his preferences. He checks boxes for “dom” and “masturbating” and puts a few checkmarks by and a circle around “face-sitting”—things he has probably never done with Caroline and feels too ashamed about to ask. Initially unsure of whether or not he should mail back the envelope, Jordan eventually follows through with a blindfolded sexfest in a hotel room with an anonymous woman. It seems too good to be true, and sure enough, it is—hence the elaborate scam and string of murders he discovers in connection with the purple envelopes.

As the wild scheme at the film’s center begins to take shape, Jordan tries to maintain control. So far, both of Cummings’ movies have been about men trying to keep face under impossible circumstances, and watching them crumble becomes cringe-worthy fun. Shot for a mere $250,000 and presented with a simple but effective formal treatment (which only occasionally reveals its cheapness), the film’s simple presentation gives Cummings the space to do his thing. One might be tempted to argue that he’s made the same film three times over, but that’s reductive. Cummings and McCabe have more on their mind than the character and genre studies of Thunder Road and The Wolf of Snow Hollow. Moreover, Jordan sinks lower than Cummings’ characters in those films. Out of manic desperation, he searches for the envelope’s origin, passing himself off as a police investigator; he hallucinates and sees conspirators everywhere; he’s more challenging to like than Cummings’ other roles. But there’s also a greater sense of purpose behind his personal chaos.

As the wild scheme at the film’s center begins to take shape, Jordan tries to maintain control. So far, both of Cummings’ movies have been about men trying to keep face under impossible circumstances, and watching them crumble becomes cringe-worthy fun. Shot for a mere $250,000 and presented with a simple but effective formal treatment (which only occasionally reveals its cheapness), the film’s simple presentation gives Cummings the space to do his thing. One might be tempted to argue that he’s made the same film three times over, but that’s reductive. Cummings and McCabe have more on their mind than the character and genre studies of Thunder Road and The Wolf of Snow Hollow. Moreover, Jordan sinks lower than Cummings’ characters in those films. Out of manic desperation, he searches for the envelope’s origin, passing himself off as a police investigator; he hallucinates and sees conspirators everywhere; he’s more challenging to like than Cummings’ other roles. But there’s also a greater sense of purpose behind his personal chaos.

Cummings and McCabe use this shame-based man, his mid-life crisis, and the story’s vast conspiracy as a way of diagnosing a social condition. Jordan feels it vital to conform to a particular image created by various cultural and social pressures. He has to project success to be successful, and that means not deviating from what he views as acceptable behavior. We live in an era where our every like, share, or search online is recorded, stored, sold, and could be used to judge and exploit us, and Jordan is terrified of being exposed as a fraud, deviant, or anything but an embodiment of success. But given so much digital tracking and surveillance, hiding one’s true self has become a thing of the past. (“I want it to be the early 2000s again!” he declares in a climactic breakdown.) Now, social pressure forces him to do the thing that proves the most difficult yet should be the easiest—talk about his feelings. But when that reality confronts someone incapable of honesty, there’s a cataclysm. Most people haven’t caught up to being transparent, and the adjustment has been challenging for some, downright punishing for others—perhaps deservedly so.

Although occasionally messy and tangential, the film and Cummings’ performance keeps us involved from moment to moment. The Beta Test is filled with those familiar comic ironies found in Cummings’ other work about unstable protagonists. At one point in a fraught late-night act, Jordan calls a recent social media connection, an old high school love interest, and brags about being five years sober with a drink in his hand. Indeed, he’s a character at odds with himself to hilarious, difficult-to-watch effect. “I’m not stressed,” he insists, “I just feel like I have a huge fucking weight on me.” The brutal irony is that the prying eyes of internet culture, which is so quick to call out bad behavior, create a reinforced artificial façade that everything is fine—especially among soulless businesspeople and Hollywood dealmakers who adopt personas for profit. Ultimately, The Beta Test yearns for honesty, even if it’s uncomfortable, yet it acknowledges that constant watchdogging creates a fear of retaliation from honest feelings that might be unpopular or rejected. Unfortunately, our culture has taught people like Jordan that difficult or complex conversations get shut down, and that you have to maintain a particular image or else. But as Caroline tells him in the end, quite achingly, “This could have been a conversation.”

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review