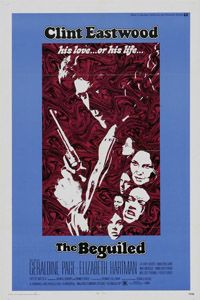

The Beguiled

By Brian Eggert |

The Beguiled marks a curious entry in the considerable director-actor partnership of Don Siegel and Clint Eastwood. An unusual picture appreciated more in Europe than stateside, the 1971 production was the third collaboration between them, following Coogan’s Bluff (1968) and Two Mules for Sister Sara from the previous year. The Civil War story involves a wounded Union soldier taking refuge in an all-girls finishing school in the Deep South. He charms them with kisses at first, but soon they become jealous of one another, which leads to everyone involved embracing less savory, rather sadistic facets of their psychology. Nothing about Siegel’s stark and hard-boiled thrillers like Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954) and The Killers (1964) suggests he was interested in making a psychosexual period drama (then again, among Siegel’s series of tough guy films appeared his paranoid science-fiction landmark, Invasion of the Body Snatchers from 1956). Eastwood, by contrast, appeared almost exclusively in Westerns and war films at this point in his career, earning his reputation in Sergio Leone’s “The Man with No Name” trilogy and Kelly’s Heroes (1970). But the masculine-centered films of Siegel and Eastwood step aside for something uncanny, deeply flawed, yet utterly fascinating with The Beguiled.

From the first scenes where injured Yankee John McBurney (Eastwood) plants a long kiss on 12-year-old Amy (Pamelyn Ferdin) to keep her quiet as a Confederate patrol passes by, the viewer should feel attuned to the film’s offbeatness. Amy brings “McB” back to the Miss Martha Farnsworth Seminary for Young Ladies, where the headmistress Martha (Geraldine Page) reluctantly takes the soldier in, vowing to keep him alive if only to turn him over to the Southern army. And yet, McB showers Martha and her young ladies with compliments and niceties within the first moments, claiming he’s a nonviolent Quaker and not a typical Union soldier. Before long, he tries any number of angles to ensure his escape back to the Union. He vows to run away with the virginal Edwina (Elizabeth Hartman), he flirts with the resident “hussy” Carol (Jo Ann Harris), and he sees an opportunity to seduce Martha. But he also thoroughly enjoys his various liaisons. Amy watches from the sideline, her pet turtle Randolph in hand, believing in her girlish way that McB really loves her. Meanwhile, a wounded crow, which Amy keeps tied up on the second story of their Mississippi plantation house until it can fly again, stands as a heavy-handed metaphor for McB.

Executive producer Jennings Lang purchased the rights to Thomas Cullinan’s 1966 novel as a Clint Eastwood property. The screenplay was written by Albert Maltz and Irene Kamp; though, unhappy with the final script, they both chose to be credited under pseudonyms: John B. Sherry and Grimes Grice. Several drafts of the script were written to cater the book to Eastwood, beginning with McBurney being changed from a twentysomething to forty (Eastwood’s age at the time). And while Cullinan’s scenario occupies the Southern Gothic genre, many critics and film historians have been reductive when describing the material as a horror picture. Perhaps it is, perhaps not. The Beguiled‘s claim to horror would seem to depend on the viewer’s perspective. Does the viewer see McB as an innocent victim imprisoned by a group of women, physically incapable of escaping his exceedingly jealous, fatherless, husbandless, and sexually repressed captors? Vincent Canby called the film a “misogynistic nightmare” in The New York Times. Or is the narrative more complicated than that? I think it is.

At first, the film might seem like it takes McB’s side, placing him in a horror movie conflict in which Man faces off against repressed, bloodthirsty Women (one of the film’s proposed titles was “The Nest of Sparrows”). But rather than tilting an obscure Civil War sex fantasy on its head, The Beguiled proves much less one-sided. Take the film’s shifting perspective from one character to another as they narrate their innermost thoughts, desires, and deceptions; this suggests the title has no exclusive reference to either McB or the ladies, but to all of them equally. Our sympathies shift throughout the film as well. McB seems like a Yankee hero until he takes advantage of the young students; but then, he gains our pity once more, albeit briefly, during the notorious leg amputation scene. Similarly, Martha could garner our compassion until we discover her twisted relationships with Christianity and her late brother. And while most of the girls prove naive and not quite fully formed characters, Amy alone deserves sympathy, as McB eventually commits the mortal sin of killing Randolph, thus unleashing preteen girl vengeance in the form of poisonous mushrooms. The film could hardly be summed up by “hell hath no fury like a woman scorned,” though the film was advertised and seen that way in many circles.

The film oozes with Freudian motivations for his female characters in problematic, notably masculine ways. From the smallest student, Amy, to the headmistress Martha, each of them is eroticized by McB’s presence, as though their sexual identities were either activated or awakened from their slumber by nothing more than the appearance of Clint Eastwood. Cullinan wrote his book during an era in which Freudian psychoanalysis became pop-psychology, starting in motion pictures as early as 1920 with the nightmare imagery in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. But it was the cinema of Alfred Hitchcock—between exploring repression in Spellbound (1945) and giving Norman Bates an Oedipal Complex in Psycho (1960)—that popularized Freudian psychoanalysis in Hollywood, therein marginalizing women and defining their psyches only in relation to men. Freud’s phallocentric discussions of sexuality, and fetishism in particular, often speak of women in a biblical-biological sense—as if they are nothing more than an incomplete piece of a man, or Adam’s rib, which informs Freud’s interpretation of how women are viewed by men, and how their lack of a female phallus leads to complexes among men.

However preferable it may have been to have a less-male psychoanalytic perspective for the film’s female characters, the Freudian elements of The Beguiled give way to another standard Freud device: the dream. Several marvelous sequences explore the warped minds at work in the film, beginning with Martha’s reveries of and sexual longings for her brother. In flashbacks, she recalls her sibling and their rolls in the grass, and she sees McB as her brother’s replacement. Elsewhere, she dreams of a ménage à trois between herself, McB, and Edwina in a passage that fades into an image of the Holy Trinity. And though the ladies often worry about patrols of men that might take advantage of the school’s student body, they should worry more about McB, who, at one point, closes his eyes to relish having a lineup of women pining for his affections. His true colors become clear when, during a drunken fit, he announces his intentions to have his fill of any young woman in the school who wants him. He begins by demanding that the school’s slave worker, Hallie (Mae Mercer, excellent in her small role), join him in the wine cellar. She replies, “You better like it with a dead black woman, ’cause that’s the only way you gonna get it from this one.” Indeed, Hallie’s presence never allows us to forget that Martha and her students are Confederate slave-owners, and therefore not all that sympathetic.

An eyebrow-raising trend in the early filmography of Clint Eastwood found the actor fending off (and encouraging) the advances of underage teenage girls (often echoed by Eastwood’s actual romances with his young female costars, including Harris), and this trend was supplemented by violence in The Beguiled. As observed by Eastwood biographer Patrick McGilligan, women who sought a sexual union with the actor in his films often found themselves ready to take his life. McB announces quite drunkenly at one point his belief in “the basic desire of women to castrate men,” and this was the very theme of Eastwood’s directorial debut: The thriller Play Misty for Me, also released in 1971, is about a radio jockey contending with an obsessed female fan after a casual one night stand. Many of Eastwood’s early films feature a woman denied her dose of Eastwood-love and, in predictable Freudian logic, she acts out through violence due to her sexually repressed state.

Shot on Belle Hélène plantation in Louisiana, the film looks atmospheric with an earthy color palette courtesy of cinematographer Bruce Surtees, who shot a dozen Eastwood pictures over the years, The Beguiled being his first. In a bookended style choice, Siegel and Surtees fade-in and, in the grim finale, fade-out to make the film look like a rusty war photograph. The nighttime shooting in candlelight also has an authentic quality. However, from Eastwood’s seventies hair to the hyper-sexual proceedings, the film exudes an air of 1970s Hollywood. Eastwood’s swagger alone characterizes and limits the film, whereas the actor later attributed The Beguiled‘s box-office failure to his character’s emasculation. McGilligan noted that Eastwood felt McB was a “loser” and, without a hint of irony, the actor told an interviewer, “My audience likes to be in there vicariously with a winner… My characters have sensitivities and vulnerabilities, but they’re still winners. I don’t pretend to understand losers.” With remarks like this, it seems as though Eastwood wasn’t aware of the kind of film he was making; neither were audiences at the time: The Beguiled made less than $1 million in receipts.

Shot on Belle Hélène plantation in Louisiana, the film looks atmospheric with an earthy color palette courtesy of cinematographer Bruce Surtees, who shot a dozen Eastwood pictures over the years, The Beguiled being his first. In a bookended style choice, Siegel and Surtees fade-in and, in the grim finale, fade-out to make the film look like a rusty war photograph. The nighttime shooting in candlelight also has an authentic quality. However, from Eastwood’s seventies hair to the hyper-sexual proceedings, the film exudes an air of 1970s Hollywood. Eastwood’s swagger alone characterizes and limits the film, whereas the actor later attributed The Beguiled‘s box-office failure to his character’s emasculation. McGilligan noted that Eastwood felt McB was a “loser” and, without a hint of irony, the actor told an interviewer, “My audience likes to be in there vicariously with a winner… My characters have sensitivities and vulnerabilities, but they’re still winners. I don’t pretend to understand losers.” With remarks like this, it seems as though Eastwood wasn’t aware of the kind of film he was making; neither were audiences at the time: The Beguiled made less than $1 million in receipts.

The Beguiled is a strange film that contains a lot of humor—some of it intentional, some not—and fuels debate about its representations of gender and sexuality. The eerie score Lalo Schifrin adds a playful, grotesque tone to the campy material, while Eastwood occupies a role that, by his own admittance, goes against his “winner” type. Most of the acting is excellent, particularly Page and Hartman’s representation of tortured, desperate virginity. Mercer, occupying the sole African American character in a Civil War film, offers mere kernels of what could have been a more complete role, but she’s also more than just an anonymous slave among white ladies. And while several aspects of the film seem confused or out of alignment in a form-follows-function sense, The Beguiled‘s peculiar and perverse setup offers a rare glimpse at something experimental in the Eastwood canon. Its ideas about sexuality may seem outdated and representative of a particular time and place in film history—the Swinging Seventies—but the filmmaking and sheer oddity of everything onscreen remain compulsively watchable.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review