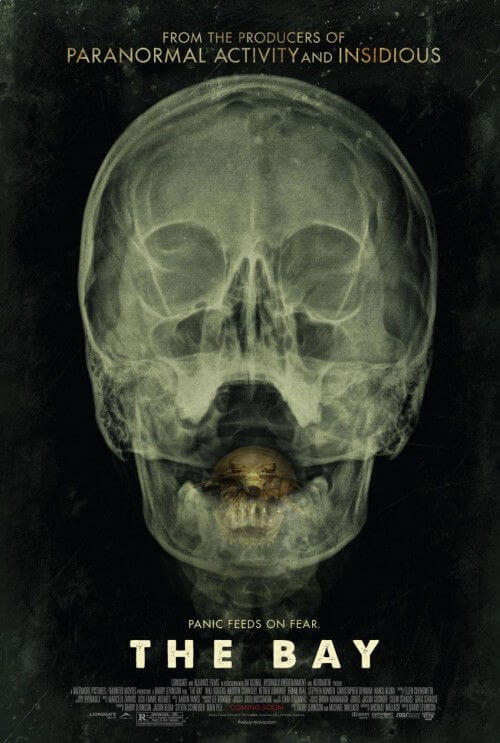

The Bay

By Brian Eggert |

With prestigious projects to his name ranging from Good Morning, Vietnam to Sleepers, the Oscar-winning Rain Man director Barry Levinson is not a filmmaker associated with the horror genre or “found footage” subgenre. Approached to make a documentary about dangerous contaminants causing massive oxygen-depleted aquatic dead zones in Chesapeake Bay, Levinson instead chose to jump on the popular (and ever-tiring) “found footage” bandwagon and make The Bay as unnerving as it is relevant. Shot in a faux-documentary style, this eco-minded B-movie fare is strangely thrilling despite its lack of strong characters or narrative. Scripted by Michael Wallach from a story by Wallach and Levinson, the film, in limited theatrical release and available on VOD, has been widely described as “Jaws meets Contagion,” concerning a deadly outbreak in a Maryland town during Fourth of July festivities.

This low-budget project from the producers of Paranormal Activity and Insidious follows inexpert reporter Donna Thompson (Kether Donohue) as she documents herself years after a 2009 incident. Confiscated footage has since been accessed via a Govleaks site, and she’s put it together to tell the story of her hometown being infiltrated by a deadly emergence of parasites from Chesapeake Bay. Thompson provides voiceover to assorted digital evidence, including images taken by victims and video conversations between CDC officials, doctors, and local authorities. Thompson was present during the outbreak, serving as a green reporter on her first job, which shouldn’t have been any more intense than having to endure a local crab-eating contest. But soon, citizens appear with mysterious bacterial boils, rashes, and pustules on their skin; they vomit blood, and their tongues go missing. A few dead bodies are found with their insides ripped out from the abdomen, and initial reports suggest a killer is on the loose. Out on the water, hundreds of fish have died, while fishing boats and swimmers find themselves attacked by chittering insect things.

But then Thompson gives us a backstory about two scientists (Christopher Denham and Nansi Aluka) conducting experiments in the bay a few weeks earlier. They maintain that nearby chicken farms dump 45 million pounds of steroid-infused chicken excrement in the bay each year, not to mention “negligible” nuclear reactor leaks that no doubt seeped into the drinking water supply. Of course, the water passes the Environmental Protection Agency’s tests with a resounding D- score, so all should be well, right? Not quite. Our two scientists find crustaceous isopod parasites have been mutated and have grown into aggressive little eaters. For reasons that remain annoyingly unclear, the mutant isopods decide to strike all at once and make a feast of the local human population. What’s most frightening about this scenario is that, aside from the detail about mutant water insects killing hundreds of people, the facts about Chesapeake Bay are mostly true.

Levinson resists shooting with traditional cameras or even commonly used Red One digital photography; instead, he uses cell phones, Skype conversations, Androids, iPads, security cameras, and police cruiser recorders to assemble his footage. He also employs a variety of audio textures to distort recordings and let our imagination fill in the blanks; a particularly horrifying scene where two cops investigate a victim’s house is heard only from outside and sounds like a nightmare come true. Refreshingly, Levinson resists those wobbly, prolonged chase scenes normally present in “found footage” movies and offers a comparatively smooth visual experience. His editor Aaron Yanes pieces together coherent if intentionally grainy footage, although his major misstep is circling back and replaying images we’ve already seen to stress a particular point made by the narrator. This unnecessary repetition of information can’t help but make the moviegoer feel as though we’re being treated like morons.

Then again, the film has the benefit of blaming the lesser aspects of its structural presentation on Thompson, since the film’s pretense is that she amassed this otherwise top secret footage. Perhaps the film’s clumsy, repetitive choices can be blamed on a novice reporter who’s never assembled a film before and doesn’t know when she’s being over-emphatic. Furthermore, though one cannot defend The Bay’s dramatic or narrative structure, because, simply, there isn’t one, the impact of the film is undeniable. The story is not about a protagonist, but about exposing the demise of an entire American town and the subsequent cover-up. As a result, not only will viewers think again before stepping into a public body of water, they’ll begin to ask questions about the water itself: where it comes from and what possible contaminants they might be swimming in or drinking. When, after the film and a web search or two, audiences begin to read about the real problems of Chesapeake Bay, Levinson’s intent becomes apparent, and we realize how successful a project this was not just as a horror movie but as an environmental message.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review