The Banshees of Inisherin

By Brian Eggert |

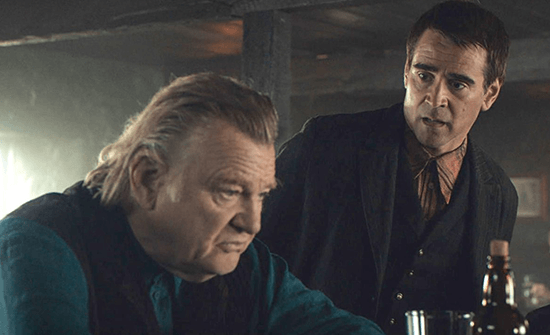

Martin McDonagh’s The Banshees of Inisherin opens with smiles and rainbows, but it leads to self-mutilation and fire. The year is 1923, and Pádraic Súilleabháin (Colin Farrell), an optimistic, simple man of Inisherin, an isle just off the Irish mainland, arrives at the home of his friend, Colm Doherty (Brendan Gleeson). But Colm doesn’t answer when Pádraic knocks for their customary 2 p.m. pint or three at the local pub; he’s inside, except he ignores Pádraic’s presence. Confused, Pádraic heads home to explain what happened to his sister, Siobhán (Kerry Condon). She jokes, “Maybe he just doesn’t like ya n’more.” Sure enough, that’s just the case. When Pádraic finds Colm at the pub later, his so-called friend tells him to “Sit somewhere else.” No, Pádraic didn’t say or do anything wrong, Colm explains. “I just don’t like you no more.” Colm has an inward, artistic disposition; convinced he only has a few years of life remaining, he wants to spend it writing music, creating his legacy on the fiddle. So it’s any wonder why they were friends to begin with—the two men have little in common. Besides Colm, Pádraic’s closest companions are his sister and a miniature donkey named Jenny, and he’s no conversationalist. So when Colm explains that “I just don’t have a place for dullness in my life anymore,” Pádraic faces the kind of existential anguish McDonagh has explored before—with Farrell and Gleeson no less, in his superb 2008 debut, In Bruges.

The dark comic setup finds Pádraic befuddled and unconvinced. He doesn’t believe it. He can’t believe it. “You do like me,” he tells Colm. But no, he doesn’t. Even the townsfolk think they were a funny pair—a thinker and “one of life’s good guys,” which is a nice way of saying Pádraic is blissfully ignorant. And so, Colm has no patience left for such “aimless chatting… with a limited man.” Regardless of how Colm presents it, Pádraic doesn’t get it; he assumes it’s an April Fools Day prank. When he presses Colm to restart their routine, he receives a stern warning and ultimatum: Should Pádraic so much as talk to him, Colm promises to use gardening shears to cut off one of his fingers. And for each infraction, another finger. Colm’s grim stubbornness is almost as severe as Pádraic’s refusal to accept he lost his friend, leading to the inevitable bloody promise. Colm chucks his finger at the front door of Pádraic and Siobhán’s home, where they share a bedroom like little children and have no doubt lived their entire lives. In another film, the detached finger would be a wake-up call for Pádraic to examine whether he’s genuinely a dullard. But McDonagh shows Pádraic watching Colm from a distance, trying to figure out his friend, while Colm looks toward the mainland, where the bombs and guns of the Irish Civil War capture his vague interest.

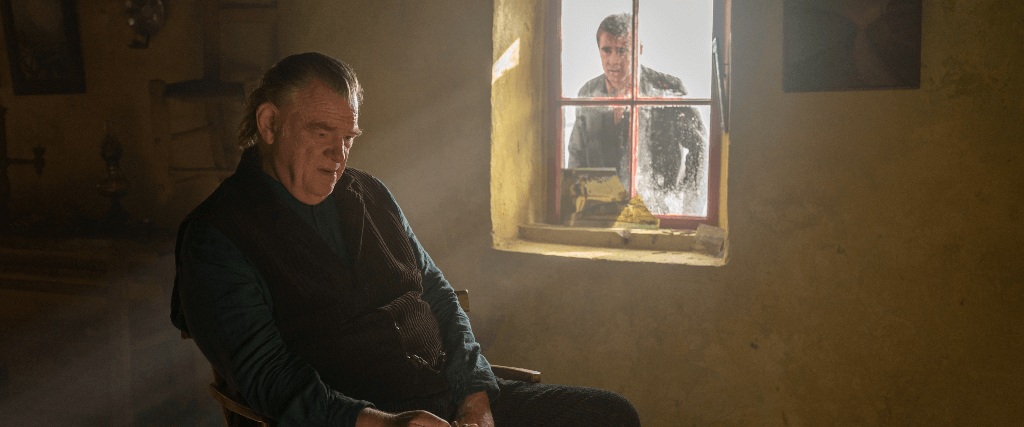

The Banshees of Inisherin unfolds almost like an Irish fable, and Ben Davis’ cinematography gives the story an appearance that would almost be idyllic if not for the existential gloom. Nevertheless, questions remain about its lesson. Maybe it’s an allegory for the Civil War, even though few on Inisherin seem to care or understand the conflict—they want to go about living their quiet lives, unconcerned about who’s winning. And if that’s the case, then perhaps Pádraic represents the Free State, content with the illusion of freedom, while Colm signifies the Irish Republican Army, willing to take a stand against British rule for his sense of self. Or maybe it’s about living an active life, whether by leaving a legacy or refusing to submit to complacency—implied by Colm’s desire to create timeless art and Pádraic’s routine existence, but also by the mythological creatures of the title that lament the passing of loved ones with a haunting shriek. Colm believes that banshees no longer scream; they quietly observe those on the island whose every moment signifies another second closer to death. Throughout The Banshees of Inisherin, there’s a lot of quiet, banshee-like observation, from the townsfolk who look upon Pádraic and Colm’s mounting conflict to the animals that seem to watch humans from outside windows to the people of Inisherin who are passive spectators to their country’s infighting.

The Banshees of Inisherin unfolds almost like an Irish fable, and Ben Davis’ cinematography gives the story an appearance that would almost be idyllic if not for the existential gloom. Nevertheless, questions remain about its lesson. Maybe it’s an allegory for the Civil War, even though few on Inisherin seem to care or understand the conflict—they want to go about living their quiet lives, unconcerned about who’s winning. And if that’s the case, then perhaps Pádraic represents the Free State, content with the illusion of freedom, while Colm signifies the Irish Republican Army, willing to take a stand against British rule for his sense of self. Or maybe it’s about living an active life, whether by leaving a legacy or refusing to submit to complacency—implied by Colm’s desire to create timeless art and Pádraic’s routine existence, but also by the mythological creatures of the title that lament the passing of loved ones with a haunting shriek. Colm believes that banshees no longer scream; they quietly observe those on the island whose every moment signifies another second closer to death. Throughout The Banshees of Inisherin, there’s a lot of quiet, banshee-like observation, from the townsfolk who look upon Pádraic and Colm’s mounting conflict to the animals that seem to watch humans from outside windows to the people of Inisherin who are passive spectators to their country’s infighting.

McDonagh’s screenplay might be his most layered and moving yet. Like his other films—In Bruges, Seven Psychopaths (2012), and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017)—it’s prone to bursts of sardonic humor and tension that leads to bloody violence, coupled with an existential quality to the characters. But McDonagh resists the usual post-Tarantino vibe that accompanies his philosophizing hitmen and cops, and instead, he reaches for something more introspective. On the surface is a quirky account of two stubborn Irishmen with nothing better to occupy their time than drinking or fiddling. But there’s subtle work beneath McDonagh’s premise that makes this his most ponderous film, hinted at by the mischievous, diffusive music by Carter Burwell—composer of melancholic scores for Charlie Kaufman (especially Anomalisa, 2015) and the Coen brothers. Watching The Banshees of Inisherin, the Coens’ influence on McDonagh’s screenplay is unmistakable, including the circularity and repetitive dialogue arrangement combined with a cynical sense of the orderless universe. But it’s no pastiche. The difference, I suppose, is that McDonagh doesn’t punish or delight in tormenting his characters in the same manner the Coens often do. While idiosyncratic, his film has genuine empathy for both Pádraic and Colm.

Even so, the film recognizes that Inisherin isn’t the ideal place for Colm to find the stimulating conversation or cultured company he seeks. Colm admits to the possibility that, in his gesture of artistic commitment, he may be “entertaining himself” to “stave off the inevitable.” He could just be bored and depressed on Inisherin, an evident problem when, in confession, the local priest (David Pearse) asks him, “How’s the despair?” And the fact that Pádraic lacks despair doesn’t vindicate Colm’s apparent feelings of hopelessness. But if he’s so depressed, Pádraic wonders amusingly, why doesn’t he just “push it down, like the rest of us?” Comic barbs like this make McDonagh’s screenplay achingly funny and relatable for depressives. Meanwhile, Siobhán faces a similar problem as Colm, but she has enough sense to lose herself in books. Condon is terrific and fiery in her scenes, and she creates a character who’s doubtlessly the smartest person on the island. At one point, Siobhán asks her brother, “Do you never get lonely?” But Pádraic has his sister, donkey, and best friend (well, had), and that’s enough. Eventually, she lands a librarian job on the mainland and takes it, tired of the petty squabbles that have become “feckin’ boring” (“feck” replaces most “fucks” here), if not tinged with madness and dismemberment.

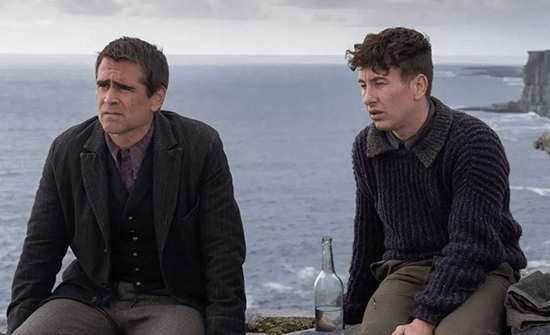

Pádraic’s only other option is Dominic—a dope played with unnerving energy (per usual) by Barry Keoghan. Siobhán reckons he is the dimmest person on the island, if not the creepiest. And he carries a torch for Pádraic’s sister and asks what interests her. Reading, Pádraic explains. “Readin’,” Dominic reflects, as though learning she has three months to live. “Feckin’ hell. Readin’.” Much like the Coens, McDonagh delights in odd supporting characters such as Dominic, who seem to be comic asides until their tragic arc reveals itself. Dominic’s father, the local policeman Peadar Kearney (Gary Lydon), “fiddles” with his son and brutally beats him most other nights, not that anyone cares enough to help him. Despite Dominic’s mental downfalls, he knows enough to step away when Pádraic settles on meanness to define the “new” version of himself—and, hopefully, that meanness will register as interesting to Colm. But Dominic cannot abide more mean people in his life; in the end, he might have been better fulfilled joining the Civil War. Elsewhere, in a more supernatural bent, the old Mrs. McCormick (Sheila Flitton)—a witchy character straight out of Shakespeare’s Macbeth—unnerves Pádraic and Siobhán, offering harsh prophecies of two deaths on the horizon.

Pádraic’s only other option is Dominic—a dope played with unnerving energy (per usual) by Barry Keoghan. Siobhán reckons he is the dimmest person on the island, if not the creepiest. And he carries a torch for Pádraic’s sister and asks what interests her. Reading, Pádraic explains. “Readin’,” Dominic reflects, as though learning she has three months to live. “Feckin’ hell. Readin’.” Much like the Coens, McDonagh delights in odd supporting characters such as Dominic, who seem to be comic asides until their tragic arc reveals itself. Dominic’s father, the local policeman Peadar Kearney (Gary Lydon), “fiddles” with his son and brutally beats him most other nights, not that anyone cares enough to help him. Despite Dominic’s mental downfalls, he knows enough to step away when Pádraic settles on meanness to define the “new” version of himself—and, hopefully, that meanness will register as interesting to Colm. But Dominic cannot abide more mean people in his life; in the end, he might have been better fulfilled joining the Civil War. Elsewhere, in a more supernatural bent, the old Mrs. McCormick (Sheila Flitton)—a witchy character straight out of Shakespeare’s Macbeth—unnerves Pádraic and Siobhán, offering harsh prophecies of two deaths on the horizon.

In the face of McDonagh’s sometimes derisory portrait of Inisherin and its unambitiously contented characters, even in contrast to their country’s Civil War, he offers a moving picture of animals. Pádraic’s miniature donkey Jenny wanders inside the home and comforts him when he’s lonely, similar to Colm’s loyal dog (a Border Collie named Morse). Their animals look in through windows, observing human behavior, just as Pádraic looks on at Colm’s new life, playing music at the pub with his musician friends. The Banshees of Inisherin seems to contain an equal measure of admiration and spite for creatures who can remain uninvolved. Their lives are more straightforward and, in the case of animals, serene. So when the priest tells Colm that “God doesn’t care” about animals, Colm acknowledges, “I fear he doesn’t… I figure that’s where it’s all gone wrong.” To be sure, the death of an animal becomes McDonagh’s most wounding turn in the film. They may not be fighting in wars or creating music that will be remembered for centuries, but they’re capable of blind and unshakable affection for their human counterparts—similar to what Pádraic had for Colm. McDonagh finds something beautiful in their desire to live without a care for human history, even if Pádraic’s similar state is less admirable.

There’s a conversation in The Banshees of Inisherin about the idle and the active, those looking at the actions of others and those acting. Where McDonagh ultimately falls remains up for debate. But the experience, gorgeously shot and compellingly dramatized with moments that shock and prompt laughter, is made all the more memorable for the performances. Condon and Keoghan’s supporting roles are the standouts. Ever reliable, Gleeson plays Colm with the intelligence, immovability, and bitterness that McDonagh and his brother, John Michael, have often written for him in films such as In Bruges, The Guard (2011), and Calvary (2014). But Farrell’s performance is the greater stretch, playing a man who doesn’t have the sharpest mind and prides himself on his niceness. The situation exhausts his pleasant demeanor, and Farrell has the skill to move Pádraic from being comically out-of-his-depth to lashing out at something he doesn’t understand. “To our graves, we’re taking this,” Pádraic attests. That kind of statement comes from someone with a shaken worldview, and he’s doggedly unwilling to accept the change. His reaction is every bit as irrational and pretentious as Colm’s childish behavior and belief that his art will last forever. Looking at the quiet sophistication of animals in McDonagh’s film, who accept everything that happens to them with grace, these men could learn a thing or two.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review