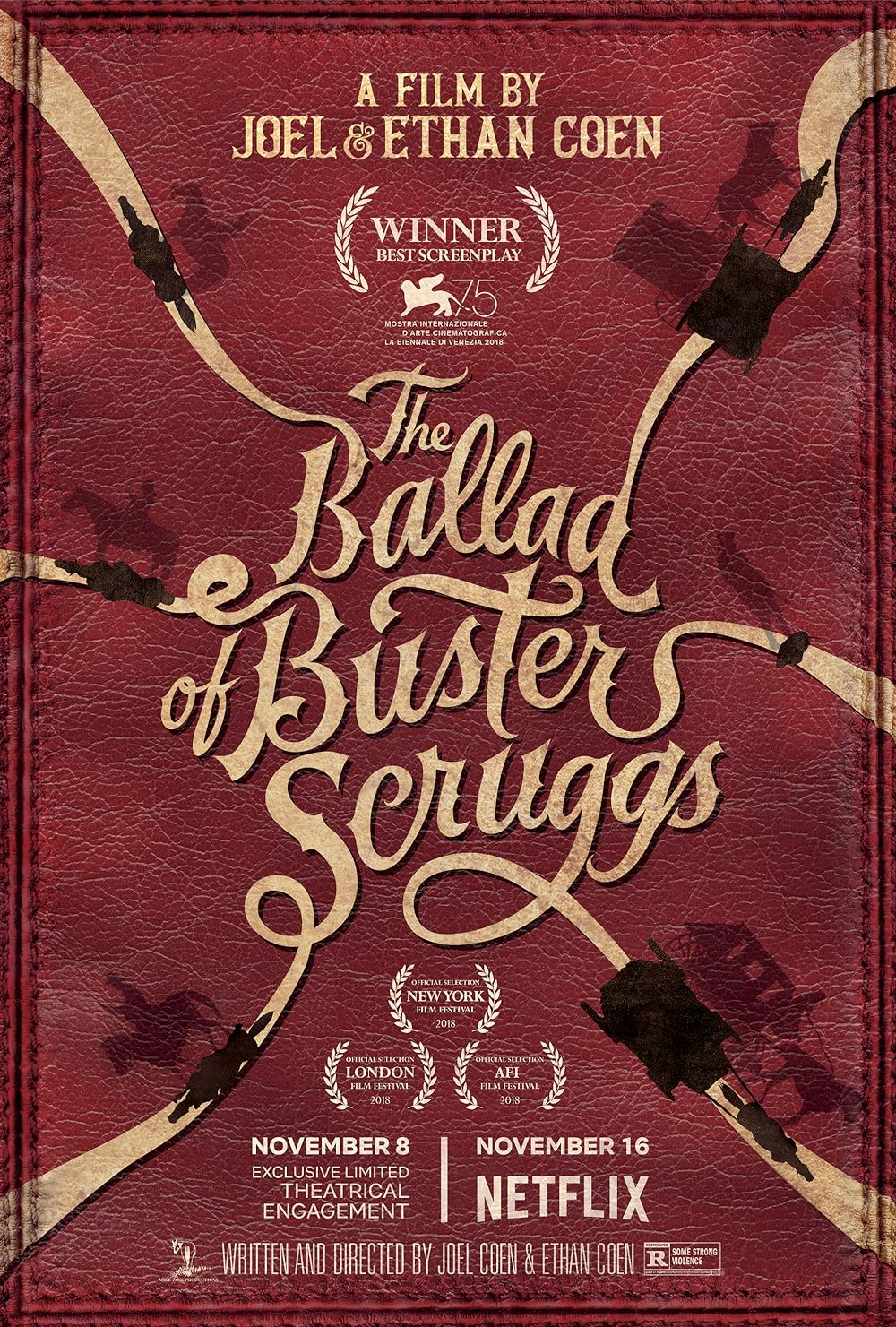

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

By Brian Eggert |

A grim and humorous rumination on mortality, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs encapsulates the varying styles of Joel and Ethan Coen, the brothers who often weigh the brevity and meaninglessness of existence in their films. Whether it’s Nicolas Cage’s ex-con in Raising Arizona conjuring the lone biker of the apocalypse from his dreams, the haunting final image of A Serious Man, or the dreaded Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men assigning fate to the randomness of a coin toss, death comes in various forms, lending their work its furtive quality. Not unlike the tonal range between these examples, their latest effort, a Western in six parts, transitions from the cartoonish to the hopelessly bleak. Along the way, it moseys through the Coens’ stylistic territory, a vast expanse that includes riotous comic absurdities, dark ironies, the hopeless search for meaning, and sobering cruelty. It’s a compendium of the Coen brothers’ cinematic dimensionality and metaphysical philosophy, set against a Western backdrop that, increasingly as it goes on, reflects their worldview in its unforgiving treatment of its characters. Almost instantly it becomes the essential film to introduce budding cinephiles to their methods and motifs, as it almost seems to summarize their entire thirty-year oeuvre.

Developed for Netflix as a television miniseries, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs eventually became an anthology film and, accordingly, should be viewed in a single sitting. It tells six stories from the Old West, though they share neither character nor locations among them. The opening recalls many a Walt Disney animated feature, where a live-action book rests on a table and, from off-screen, a rugged hand turns the pages of this weathered clothbound volume. That book, copyrighted in 1873, bears the title “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs and Other Tales of the American Frontier.” Although Buster Scruggs (Tim Blake Nelson), a goofy little man clad in white and a 10-gallon hat, appears only in the first tall tale, his character’s trajectory could be a lesson to others throughout, while his fate marks the first curve of the film’s elliptical shape. In the proceeding stories of bank robberies, hangings, drownings, shootouts, wagon-trains, and stagecoaches, the Coens portray a Western landscape indifferent to those inhabitants who brave it. And while over the years they may have earned their reputation for being cruel to their characters, their treatment demands consideration for its lessons—even if the lesson is that there is no lesson.

Strumming a guitar with a Gene Autry smile and a twang in his voice, Nelson’s Buster Scruggs could be a caricature not unlike Hail Caesar!’s Hobie Doyle; he looks and behaves like a cornball on a 1930s Hollywood picture. Scruggs appears in the first episode on horseback, riding a dusty trail and breaking the fourth wall. He’s another in a long line of Coen narrators who appears as genial as Sam Elliot’s The Stranger in The Big Lebowski, but he has more in common with M. Emmet Walsh’s ruthless private eye in Blood Simple who confessed, “What I know about is Texas, and down here, you’re on your own.” The same is true of Scruggs, who boasts to his audience that he’s a wanted man before stopping at a watering hole, where he’s insulted and denied a drink by the resident outlaws, to which he responds with a volley of bullets that makes short work of, well, everyone. Proud of his own superior gunslinging, Scruggs then ambles into Frenchman’s Gulch, a small Western town for a game of cards, a song, and a pair of standoffs in the street. The violence recalls a Looney Tune starring Yosemite Sam, where a gunshot to the head leaves a blackened face and hair frayed back. After Scruggs learns he “can’t be on top forever,” the Coens depict his ascent with wings and a harp in true cartoon style.

Indeed, each episode adopts a unique influence, making each an exceptional pastiche of Western imagery. After the page turns to the second story, we find ourselves in a Sergio Leone world of extreme close-ups and spare soundscapes, recalling the opening sequence of Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)—complete with tanned, glistening skin and the persistent squeak of rusted metal. James Franco appears as a bank robber whose plans are undone by a wily teller (Steven Root) well-versed in dealing with bandits. Before the story’s end, Franco finds his neck in a noose, twice, for a bitter irony reminiscent of Tales from the Crypt-brand humor. But if the first two stories seem to revel in comical twists of fate, nothing so trivial follows, as the remaining four venture into darker, sadder territory. Moreover, the remaining sections inform the comparatively lighthearted earlier two, resituating them with a thoughtful meditation on death, pride, and the futility of best-laid plans in the face of human greed and cruelty.

Indeed, each episode adopts a unique influence, making each an exceptional pastiche of Western imagery. After the page turns to the second story, we find ourselves in a Sergio Leone world of extreme close-ups and spare soundscapes, recalling the opening sequence of Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)—complete with tanned, glistening skin and the persistent squeak of rusted metal. James Franco appears as a bank robber whose plans are undone by a wily teller (Steven Root) well-versed in dealing with bandits. Before the story’s end, Franco finds his neck in a noose, twice, for a bitter irony reminiscent of Tales from the Crypt-brand humor. But if the first two stories seem to revel in comical twists of fate, nothing so trivial follows, as the remaining four venture into darker, sadder territory. Moreover, the remaining sections inform the comparatively lighthearted earlier two, resituating them with a thoughtful meditation on death, pride, and the futility of best-laid plans in the face of human greed and cruelty.

Throughout, the Coens pay tribute to the likes of John Ford and other classical Western progenitors, but they nod more frequently to post-modern and revisionist examples. The third episode, for instance, reminded me of Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) in how Warren Beatty’s fur-coated, dim-witted pimp has a counterpart in Liam Neeson here. Both men attempt to make a buck by presiding over a lucrative business. Neeson’s nearly wordless performance in the aptly named “Meal Ticket” is that of a traveling impresario whose main attraction, a limbless orator (Harry Melling) whose impassioned performances include everything from Shakespeare to “The Gettysburg Address,” has ceased in his novelty. Their relationship, purely business, comes to a tragic end when he finds a more crowd-pleasing alternative. Since anthology films often beg the viewer to consider which among the stories were their favorites, this was mine, as the selection of hopeful writings performed by the doomed entertainer gives way to a profoundly depressing counterpoint whose poignancy lingers well after the film’s end.

The stories continue, each featuring a new set of renown actors that occupy familiar tropes and situations; however, in the Coens’ hands, customary Western stories reveal the existential underpinnings of everything that came before. Episode four, titled “All Gold Canyon,” is a Man vs. Nature yarn on par with The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) or The Revenant (2015). Tom Waits plays a grizzled prospector whose relationship with Nature is signaled by the conspicuous disappearance of the butterflies, deer, and even minnows in the idyllic valley where he mines for gold. Afterward, Meek’s Cutoff (2010) by Kelly Reichardt could not help but come to mind during “The Gal Who Got Rattled,” the sixth episode, as both feature Zoe Kazan on the Oregon Trail. The Coens use Kazan as a bastion of innocence and moral goodness—their oft-used role for women from Marge Gunderson to Carla Jean Moss. Similar to Moss, she falls victim to the West’s limited roles for women. The final tale, called “The Mortal Remains,” takes place almost entirely in a stagecoach, and the setting, combined with the Coens’ affinity for skillful wordplay, evoked Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight (2015).

Beyond the abundant reference points in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the Coens demonstrate their formal control in a beautiful, richly realized production. Shot by Bruno Delbonnel, their cinematographer on Inside Llewyn Davis, the film often has a dreamy look, as though we’ve entered the land of Western myth as painted by Charles Marion Russell or Albert Bierstadt. Since they’re drawing from a narrative tradition that includes everyone from Jack London to Sam Peckinpah, each segment has a distinct appearance that nonetheless amounts to a cohesive whole. Certainly, the rhythm of each story, edited by the Coens under their pseudonym Roderick Jaynes, has a distinct pace, and yet each is conspicuously a work authored by the siblings. Their aesthetic emerges in how they blend their love of film history and film grammar through their inimitable voice: a cynical outlook combined with their frequently speechifying characters who remain a joy to behold, even if the worlds they inhabit sometimes betray or use them up in cruel ways. And what Coen film would be complete without Carter Burwell’s melancholy notes to underscore its woeful passages?

Beyond the abundant reference points in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the Coens demonstrate their formal control in a beautiful, richly realized production. Shot by Bruno Delbonnel, their cinematographer on Inside Llewyn Davis, the film often has a dreamy look, as though we’ve entered the land of Western myth as painted by Charles Marion Russell or Albert Bierstadt. Since they’re drawing from a narrative tradition that includes everyone from Jack London to Sam Peckinpah, each segment has a distinct appearance that nonetheless amounts to a cohesive whole. Certainly, the rhythm of each story, edited by the Coens under their pseudonym Roderick Jaynes, has a distinct pace, and yet each is conspicuously a work authored by the siblings. Their aesthetic emerges in how they blend their love of film history and film grammar through their inimitable voice: a cynical outlook combined with their frequently speechifying characters who remain a joy to behold, even if the worlds they inhabit sometimes betray or use them up in cruel ways. And what Coen film would be complete without Carter Burwell’s melancholy notes to underscore its woeful passages?

Meantime, the film contains countless individual moments that hold a place in the viewer’s mind, either by their incredible beauty, caustic wit, or lasting horror. A scene where Waits climbs a tree to steal eggs from an owl’s nest, and then thinks twice before taking them all, seems to be the universe’s sole reason for allowing him to survive a gunshot that “didn’t hit nothin’ important!” When Kazan sits on a horse, watching prairie dogs emerge from their underground tunnels, her laugh is infectious, since her character has emerged from a dire situation into one of hopeful romantic possibility. But every joy on the Western frontier comes with a price—it’s an equalizing power on par with karma or Newton’s third law. Perhaps that’s the overarching lesson imparted by Buster Scruggs, and why the film’s title bears his name, not a title from the anthology’s other stories.

“People are all pretty much the same,” resolves a rough trapper (Chelcie Ross) in the stagecoach during “The Mortal Remains.” Thus begins a debate amongst the fine lady (Tyne Daly), the Frenchman (Saul Rubinek), and two bounty hunters (Brendan Gleeson, Jonjo O’Neill) about whether or not people fall into one of two camps: upright or sinners. As the discourse unfolds in winding Coen-fashion, the viewer becomes appreciative of the fine performances and wordsmithing on display, and the themes of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs come together not with the characters’ violent demise—though that would align it with the proceeding stories. It’s far more existential and even primal in the way the film circles around, as most Coen films do, to the simple and unforgiving notion that the meanings people assign to their lives rarely matter. Everyone ends up dead one way or another. This theme has reoccurred throughout their body of work, but it finds a historical and narrative kinship on the Western landscape, a place legendary for its indifference to the ambitions of those who sought to conquer it.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review