The Artist

By Brian Eggert |

In the latest George Valentin adventure, our enduring hero has been captured by criminals and strapped down for a torturous interrogation. Electrodes fastened to his head send shocks through his body, but he remains steadfast. Valentin screams, “I won’t talk! I won’t say a word!” And in fact, we don’t hear a thing, because talkies haven’t yet emerged. We’re watching the premiere of a silent movie at the Orpheum Theater in downtown Los Angeles. The year is 1926, and Valentin, an actor cut from the same cloth as Silent Era stars Douglas Fairbanks and Rudolph Valentino, watches himself onscreen from backstage. With the help of his trusty terrier Uggy, Valentin’s hero escapes the clutches of evil and saves the day. As the music from his new picture fades out and “The End” appears onscreen, the audience breaks into enthusiastic applause. But, again, we hear nothing. Valentin’s film is a silent within a silent.

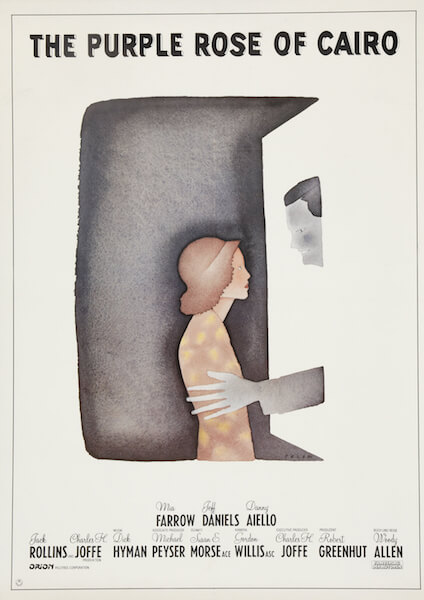

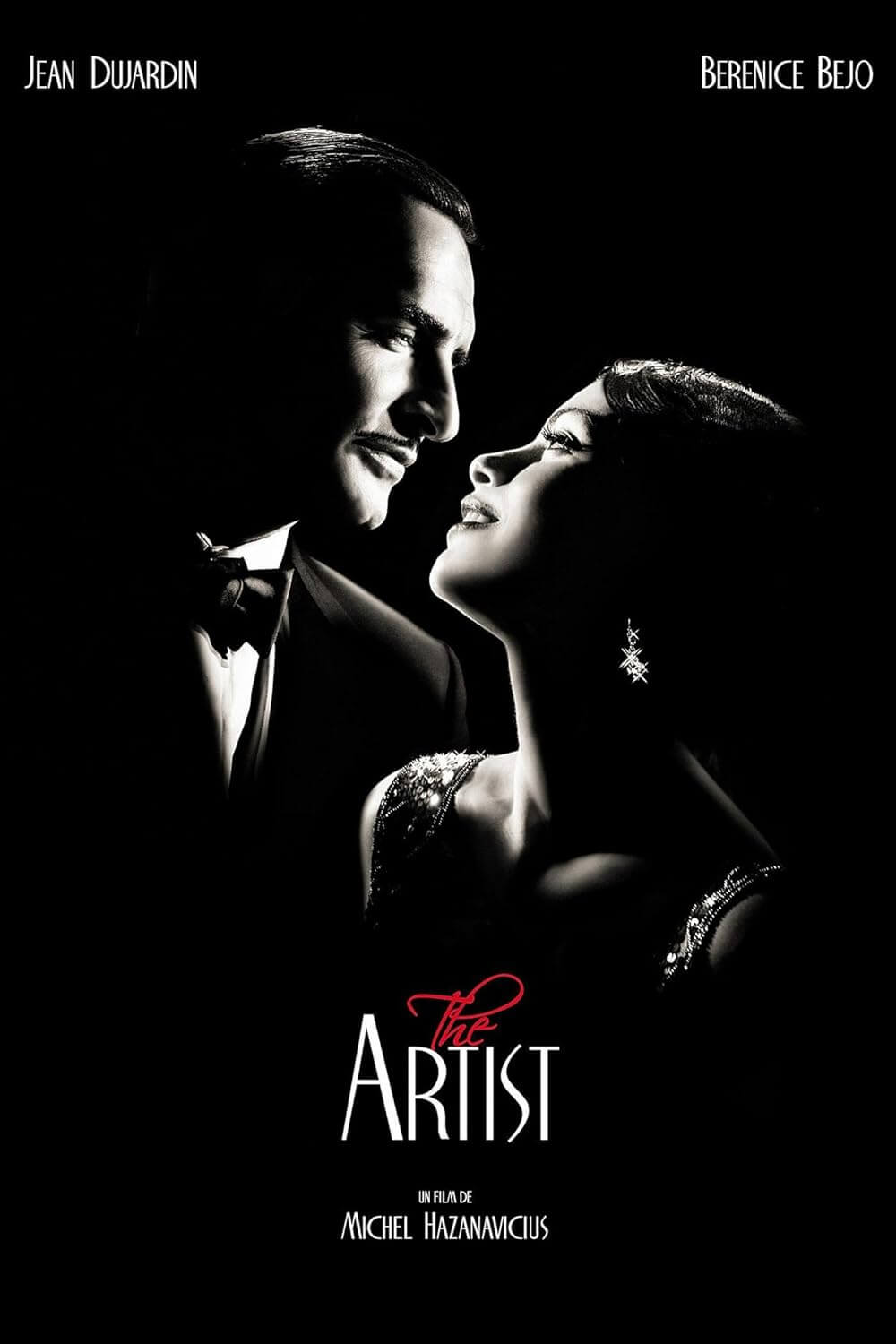

Structured for the ambitious goal of universal appeal, French writer-director Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist is a small miracle—or maybe a big one: a modern silent motion picture presented not only in black-and-white but in the classic 4:3 aspect ratio and almost entirely dialogue-free. It’s the opposite of everything that sells at the box office today, and it’s a pure delight from start to finish. The French production was shot in Hollywood using locales and props from the bygone Silent Era, while cinematographer Guillaume Schiffman filmed it in color and then remastered his prints in monochrome. Composer Ludovic Bourse’s score provides the emotional voice; English-language intertitles provide the dialogue—but what was it Sunset Boulevard’s Norma Desmond said? “We didn’t need dialogue! We had faces!” Hazanavicius has two magnificent faces in his picture. Handsome and charismatic French actor Jean Dujardin, the star of the director’s hilariously ironic spy spoof series OSS 117, plays veteran silent film star, George Valentin. Hazanavicius’ wife, the beautiful Argentinean actress Bérénice Bejo, plays the young Peppy Miller, a fresh face for cinema’s future: Talkies.

Outside of Valentin’s opening night, he bumps into doting fan Peppy, who captures front-page glory when Valentin accepts a kiss from his admirer, much to the chagrin of Valentin’s neglected wife (Penelope Ann Miller). Before long, Peppy has found her way onto the Kinograph Studios lot and, despite objections from cigar-chomping studio boss Al Zimmer (John Goodman), she wins a role as a dancer in Valentin’s next silent. But times are changing, and Kinograph plans to shift their investments entirely into sound technology, which Valentin, in all his considerable pride, waves off as a fad. He’ll have no part of it, and as a result, he’s left to make independently produced-directed-written stinkers bound for box-office failure. Meanwhile, Peppy, with all the charm of Clara Bow and Paulette Goddard, emerges as Kinograph’s new screen star, but with a voice. After the stock market crashes and his inevitable divorce leaves him with nothing, Valentin hits rock bottom, with only empty booze bottles and his ever-present pup Uggy to keep him company. From the limelight, Peppy wants to help Valentin’s career, but will his stubborn pride allow it?

The Artist’s story is so simple, yet brilliant when paired with Hazanavicius’ devotion to silent film conditions. Developmental myths firmly in place within modern Hollywood, there’s certainly an inclination to call them silent film “limitations,” but after this experience, one could hardly describe Hazanavicius’ formal approach as limited. Nothing about how he effectively directs our emotions via age-old techniques could ever be called limited. But not only is this a joyful, funny, and moving experience, it’s also a historical journey through a period too easily forgotten by contemporary moviegoers. Much like Martin Scorsese’s family adventure Hugo, this film is as entertaining as it is passionate about film history and the wonder to be had from early cinema. Except, unlike Scorsese, Hazanavicius integrates his film with his subject matter by becoming the very thing he seeks to embrace, whereas Scorsese used a very modern approach in his homage to film history and preservation. Both films result in a cinephile’s reverie, but Hazanavicius transports the viewer in a way no sound effort could ever manage.

In his considerable bag of tricks, Hazanavicius’ greatest assets are his actors. Dujardin has the smile of Gene Kelly, the presence of Errol Flynn, and the physical know-how of Charlie Chaplin. His comic timing is impeccable; he can dance, swashbuckle, and submit dramatics on a theatrical scale. For his role, he won the Best Actor award at the Cannes Film Festival, and if there’s any justice in the universe he’ll win an Oscar too. Here, he has an expressive, over-the-top quality about him that seems almost impossible to fit into contemporary movies, but he feels wonderfully at home in Hazanavicius’ films set in the ‘20s and ‘50s. Bejo, too, has airs that belong in Pre-Code cinema, and likewise deserves awards consideration. But lest we forget Uggy, who delivers 2011’s best dog performance in a significant year for terriers, following Arthur in Beginners and Snowy in The Adventures of Tintin.

Although production designer Laurence Bennett and the costumes by Mark Bridges create a cinematic time capsule for today’s audiences, Hazanavicius isn’t just making a silent film. He plays with his audience to remind us that we’re watching a silent film, which is astoundingly easy to forget once we’re engaged in the proceedings. The opening sequence, for example, offers that moment where we expect to hear Valentin’s audience cheering in their ovation. Instead, their applause is noiseless, and our expectations are abruptly readjusted. Later, after Valentin learns that sound films will be the future, there’s an inspired nightmare sequence in which he can hear sound effects but can’t make them. He hears footsteps, wind, and the clang of falling objects, but he himself cannot speak. It drives him so mad that he runs into the street screaming, yet not a peep is heard. It’s a premonition of his waning profession and an ingenious way to represent anxieties felt by all silent film stars going into the 1930s.

Like his two OSS 117 films (Cairo, Nest of Spies and Lost in Rio), which were set in the 1950s and also adhered to that era’s cinematic rules, Hazanavicius employs a number of winks and nods to the filmmakers that inspire him. After Valentin tears apart Peppy’s room with her George Valentin memorabilia, the camera pulls back to reveal a shot taken from Citizen Kane. Bourse’s almost continuous music not only calls to mind but mirrors Bernard Herrmann’s score in Hitchcock’s Vertigo during the finale, when Valentin’s downward spiral reaches its lowest. The references go on and on for the attentive viewer, citing everyone from Chaplin to Fritz Lang. One of the most endearing qualities for Hazanavicius’ audience is his love of cinema, because chances are, if you’re watching an independently produced French black-and-white silent film released in an American arthouse theater, you love cinema just as much as Hazanavicius does.

There’s more magic and wonderment to be had from The Artist than any CGI effects, 3D presentation, or IMAX spectacle can bring. Hazanavicius charts a transition in formats from silence to sound but never strays from the technical intricacies of silent filmmaking until the last endearing scene. In doing this, Hazanavicius shows all the instincts of a skilled modern filmmaker, but also a Silent Era filmmaker. His chameleon-like approach to his chosen era’s style notwithstanding, Hazanavicius’ personal touches, punctuated by his star Dujardin, are unmistakable. Through the narrative trappings of a thoughtfully constructed Hollywood melodrama, so filled with comic and tragic moments, the film reminds us that time is merely a matter of perspective, and how yesteryear’s motion pictures are not as irrelevant or outdated as some may believe. With any luck, Hazanavicius’ arthouse film will reach mainstream audiences to relay this message, and incite newfound interest and adoration for the filmmakers who inspired him.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review