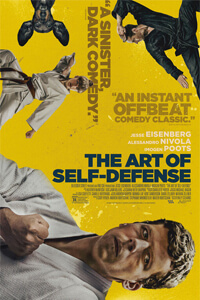

The Art of Self-Defense

By Brian Eggert |

Riley Sterns’ The Art of Self-Defense features Jesse Eisenberg as Casey, an anxious and fearful accountant determined to protect himself after narrowly surviving a brutal attack. Still reeling from the trauma weeks later, he resolves to take classes at a strip-mall karate school. “I wanna be what intimidates me,” he confesses to his instructor, played by Alessandro Nivola, an intense weirdo who insists his name is “Sensei.” But Casey is intimidated by toxic masculinity, which he experiences in abrasive parking lot interactions or watching the American Psycho-esque boy’s club at the office. Skinny and weak, and making the most of Eisenberg’s typecasting as a nebbish, Casey transforms himself into the thing he fears and despises. The material may read as darkly clever and relevant to some, but Sterns has simply Frankensteined together familiar ideas from other material, using distinct methods of satire and irony employed by other filmmakers. It’s capably made and acted, but the film doesn’t have anything to say that hasn’t been said, and said better, elsewhere.

This is a film in which every quality demands comparison to other, superior films. As with Sterns’ previous effort, his 2015 de-programming thriller Faults, the writer-director employs a familiar visual and tonal style. His cinematographer Michael Ragen uses a muted color palette of amber hues and mannered, intentionally composed shots that recall Denis Villeneuve’s work on Enemy (2013). His actors speak with an affected modulation in their voice, matter-of-factly stating bitter truths and plain facts with the same emotionless emphasis. When Casey orders multicolored leather belts so his fellow students can wear their karate colors outside of class, one of them observes, “I like it because it’s the color of my karate belt, and also because it holds up my pants.” Stating the obvious in a stilted way becomes a source of ironic humor, and given the hypermasculine karate milieu, the film plays like Jody Hill’s Foot Fist Way (2008) in the manner of Yorgos Lanthimos.

Much of the film involves Casey submerging himself into Sensei’s obscure vision of what a masculine lifestyle should look like. He tells Casey to stop learning French because the French are associated with surrender; instead, he should learn the language of a “tough country” like Germany or Russia. Casey has a German dog, a timid Dachshund, which Sensei says he should replace with a more intimidating German Shepherd. Heavy metal is the best music, says Sensei, because it is “the most aggressive.” Though, one can’t be sure what to make of Sensei’s lessons to “punch with the foot and kick with the fist.” Sensei teaches that qualities of masculine aggression lead to confidence, which is bad news for his most enthusiastic student, the brown belt Anna (Imogen Poots), who is regarded as weaker and inferior to the male students. Presented with ironic distance, these touches prove mildly humorous and occasionally jolting, especially after the Sensei’s real ambitions with his mysterious “night class” become evident.

Sterns underscores every point with a visual gag, though sometimes it results in a laugh, other times it results in a gasp—and sometimes both. The film offers several violent shocks, which the characters receive with a comical non-reaction. There’s a moment when Sensei disciplines a defiant student by severing his arm, and it recalls when John C. Reilly was punished with a toaster in The Lobster (2015). It’s a comically extreme method of correction to which everyone seems accustomed. These ironic moments also seep into the nostalgic, mid-1990s setting. Casey’s answering machine, boxy television set, and apparent inaccessibility to pornography isolate him in a sort of non-period, somewhat in the past, but also outside of time as many recent satires tend to be. Despite the affected coldness of the setting, Eisenberg is naturally sympathetic in this sort of role—watch his similar performances in Zombieland (2009) and The Double (2014)—and his screen presence invests the viewer in Casey.

It will be impossible for any cinephile to watch The Art of Self-Defense without Fight Club coming to mind. Beat for beat, Sterns, either by intention or staggering coincidence, follows the plotline of Chuck Palahniuk’s novel (or, if you prefer, David Fincher’s film). Both involve a weak man who unleashes his inner masculine rage by joining a group of fighters. Both feature a group, led by a charismatic mentor figure who embodies the protagonist’s ideal, that spars as a pastime, allowing its members to create a more confident sense of self. But their meetings move beyond physical encounters; they lead into an organization bent on enlisting new members through criminal acts (prank terrorism in Fight Club, random beatings in Sterns’ film). Inevitably, after being blackmailed by his mentor when he discovers the truth, the protagonist realizes he no longer needs the increasingly extreme group, and he rebels against it. Both stories resolve the conflict in about the same way.

The comparisons, as you might imagine, are distracting. Once the viewer notices them well before the midpoint of the film, it’s a challenge to watch The Art of Self-Defense without anticipating every development in the story, as predicted by Fight Club. It’s a quality that, when combined with the familiar role for Eisenberg and the increasingly common ironic tone of the film, drains the material of any originality or investment from the viewer. Certainly, there’s a hypothetical moviegoer who is unfamiliar with Fight Club or Lanthimos’ brand of satire, and they’ll probably enjoy Stearns’ film. And like Fight Club, there’s a risk of the audience missing the point entirely and wanting to start their own macho boxing society (a few bros exiting the theater after The Art of Self-Defense described it as “badass”). But setting aside its oppressive familiarity, there are some worthy questions about gender here that demand exploration, though they’re secondary to the awkward humor and stifling irony of it all.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review