The Animal Kingdom

By Brian Eggert |

“Strange days, eh?” says one driver to another in stalled traffic. Both have just seen someone evolving into a birdman, complete with one wing, one arm, and talons, screech and break free of an ambulance and escape his captors—by no means a common occurrence. “Strange days,” the other driver agrees with a shrug. Their world has been disrupted by the emergence of mutations spurred by a disease, transforming people into various humanoid animals. There’s no cure, and the treatments remain experimental and unproven. People change into a wide range of animal types, morphing into furry quadrupedal beasts, growing armadillo-like armor, or developing tentacles with a sudden craving for seafood. The results have no discernable pattern; the only constant is that some people change. But when the change occurs, are they still people? And if they become something other than how we traditionally define humanity, do they deserve the same treatment as people? What has to occur for a person to no longer be considered human in society’s eyes? French director Thomas Cailley conceives a charged metaphor for othering in The Animal Kingdom, an imaginative and moving science-fiction story that will resonate with anyone who’s experienced feeling different, ostracized, or discriminated against.

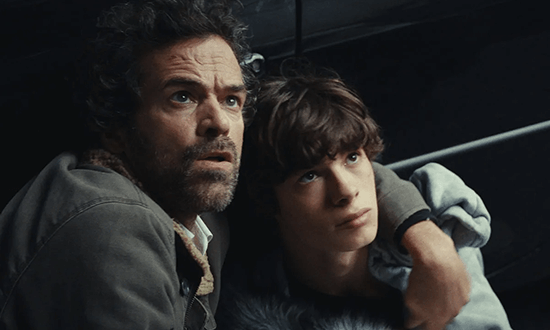

The story centers on 16-year-old Émile (Paul Kircher) and his father, François (Romain Duris), who have intimate experience watching this disease work. When their respective mother and wife, Lana, started mutating, she violently lashed out at Émile, leaving him scarred. The authorities now mandate her medical supervision, including experimental treatments that slowed the advancement of her disease. Émile struggles to recognize his mother’s new, furry face, but François sees natural beauty in what’s happening. A health advocate who preaches against a sedentary lifestyle and processed foods, François believes in getting outside and living in harmony with Nature. His wife’s change is another natural development that should be received with an open heart and understanding. Most of society doesn’t agree, calling those impacted by the disease “creatures” or “monsters,” or more commonly “les bestioles,” which translates to “critters.” It’s more than just a cruel label; the authorities have also tried to quarantine those impacted in the Center—a research facility that sounds more like a prison.

Within the first few glimpses of people changing into animals, their flesh tearing to make way for some new protrusion, Cailley calls on genres from body horror to environmentalist science fiction. Surely, thoughts of David Cronenberg’s “new flesh” in Videodrome (1983) and the embrace of mutation as evolution in Crimes of the Future (2022) come to mind while watching The Animal Kingdom. Similarly, there’s an appreciation of the Kantian sublime—what might be considered horrific yet strangely beautiful—recalling Julia Ducournau’s embrace of nasty bodily transformations in Titane (2021). Ducournau’s Raw (2016) also feels like an inspiration here, when the story becomes one of youthful self-discovery. Cailley’s film prompts thoughts of Alex Garland’s Annihilation (2018) as well, which considers Nature’s capacity to destroy as a method to promote adaptation and growth. All of these ideas linger in the viewer’s mind, without Cailley’s film feeling derivative or even referential. The filmmaker explores his premise without constantly pointing out what cinema inspired him, which feels almost novel in today’s overly allusive movies.

Within the first few glimpses of people changing into animals, their flesh tearing to make way for some new protrusion, Cailley calls on genres from body horror to environmentalist science fiction. Surely, thoughts of David Cronenberg’s “new flesh” in Videodrome (1983) and the embrace of mutation as evolution in Crimes of the Future (2022) come to mind while watching The Animal Kingdom. Similarly, there’s an appreciation of the Kantian sublime—what might be considered horrific yet strangely beautiful—recalling Julia Ducournau’s embrace of nasty bodily transformations in Titane (2021). Ducournau’s Raw (2016) also feels like an inspiration here, when the story becomes one of youthful self-discovery. Cailley’s film prompts thoughts of Alex Garland’s Annihilation (2018) as well, which considers Nature’s capacity to destroy as a method to promote adaptation and growth. All of these ideas linger in the viewer’s mind, without Cailley’s film feeling derivative or even referential. The filmmaker explores his premise without constantly pointing out what cinema inspired him, which feels almost novel in today’s overly allusive movies.

When François relocates to a small town near where Lana is in treatment at the Center, Émile enrolls in a temporary high school and immediately notices changes. He can no longer tune out background noise, has a newfound penchant for licking, and his head seems to wobble on his neck as though searching. If not for the hairy back and tiny claws emerging from under his fingernails, it might seem like Émile has ADHD, similar to his new classmate, Nina (Billie Blain), who’s drawn to him. At the same time, François befriends Julia (Adèle Exarchopoulos), a member of the local gendarmes assigned to locate “critters” who escaped from a transport crash, including François’ wife. Although the nearby woods remain off-limits given the dangers posed by those who have changed, father and son head in regardless, hoping to locate their wife and mother before the gendarmes, relying on the scent of their clothes and blaring François and Lana’s song to draw her in. It’s there that Émile returns alone to explore his changing body. All the while, anxiety builds in anticipation of what Émile will become and how his classmates and father—or worse, the local militia taken to hunting down “critters”—will react.

Meanwhile, Cailley explores a complex father-son relationship, with a rebellious son and a father who’s prone to hypocrisy: Émile is scolded for eating processed meat, which François purchased; François tells Émile not to make noise in the woods, but then he starts yelling. Then, he confronts Émile with the wolf claws he finds in the drain, as though showing him cigarettes or drugs he found in his son’s bedroom. Even someone as committed to evolution and Nature as François struggles to accept that his child may no longer resemble the person he raised. But Émile shouldn’t have to feel embarrassed, as his father soon realizes. Cailley acknowledges that there’s a point where every parent must stop trying to control their child’s development and let the kid grow up and experience life on their terms. Duris is excellent in his role, but Kircher’s rather primal, cagey performance proves central to The Animal Kingdom; at times he behaves like an animal in a person suit, yet the actor doesn’t rob Émile of his humanity. Exarchopoulos feels somewhat peripheral to the narrative for such a well-known performer, though her subtle expressions of empathy add much to her role.

The film was a major hit at France’s César Awards, earning several technical prizes for Best Cinematography, Best Sound, Best Original Music, Best Costume Design, and Best Visual Effects, among its twelve nominations. Shot with handheld cameras by cinematographer David Cailley, the director’s brother, The Animal Kingdom looks like an art film with a raw, human immediacy, not a special FX extravaganza. Andrea Laszlo De Simone’s score adds a lyrical yet urgent quality to the storytelling, accented by percussive breaths in and out. An earthy realism marks the visual presentation, even when animal-human hybrids appear onscreen, rendered using mostly convincing CGI. Among the best effects is the aforementioned birdman, Fix (Tom Mercier), who emerges along with a chameleon girl in the second act. Visited by Émile, Fix becomes more birdlike every day, his beak bursting out of his nose, his feathers peeking out of his skin. But he is determined: “I’m gonna be sublime,” Fix declares. It’s a tender subplot that finds Émile helping Fix learn how to fly, and then being a friend when a severe screech replaces Fix’s capacity for speech.

The film was a major hit at France’s César Awards, earning several technical prizes for Best Cinematography, Best Sound, Best Original Music, Best Costume Design, and Best Visual Effects, among its twelve nominations. Shot with handheld cameras by cinematographer David Cailley, the director’s brother, The Animal Kingdom looks like an art film with a raw, human immediacy, not a special FX extravaganza. Andrea Laszlo De Simone’s score adds a lyrical yet urgent quality to the storytelling, accented by percussive breaths in and out. An earthy realism marks the visual presentation, even when animal-human hybrids appear onscreen, rendered using mostly convincing CGI. Among the best effects is the aforementioned birdman, Fix (Tom Mercier), who emerges along with a chameleon girl in the second act. Visited by Émile, Fix becomes more birdlike every day, his beak bursting out of his nose, his feathers peeking out of his skin. But he is determined: “I’m gonna be sublime,” Fix declares. It’s a tender subplot that finds Émile helping Fix learn how to fly, and then being a friend when a severe screech replaces Fix’s capacity for speech.

In lesser hands, this scenario might befit an X-Men reboot or otherwise glamourized Hollywood production that values special effects and action sequences over its metaphors. But Cailley’s interest remains in emotional dynamics first, with spectacle and commercially familiar storytelling as an afterthought. The film is so successful as a work of art because it has the potential to connect to a wide range of viewers who will identify with what occurs. Instead of taking an easy route and resolving to merely entertain, which it does, The Animal Kingdom offers a rich symbolism. The story could be an allegory for gender transition, body dysmorphia, coming-of-age changes, racial prejudice, or religious discrimination. One might even read the story as an animal rights analogy on par with Okja (2017), where the emotions and intelligence demonstrated by animals stand as proof that they shouldn’t be caged, farmed, or killed by humans. Certainly, Nina remarks during the St. John’s Day festival that, historically, the event included people bagging and burning cats to ward off bad luck. But loving cat owners will attest that felines have rich personalities that qualify as non-human people. Any worthy pet owner would do the same.

However the viewer interprets The Animal Kingdom, Cailley’s ripe symbolism calls for humane behavior between humans but also between humans and animals. François champions the notion of “cohabitation” with the new human-animal hybrids. They’re not going away, so why create a conflict or an untenable situation? There’s no sense in trying to contain or stigmatize difference; it’s inevitable. Doing so only leads to intolerance, prejudice, or worse, an attempt to contain or exterminate. Human beings tend to rob other groups of their humanity by associating them with animals and using that association to justify all manner of horrible crimes. So when Cailley’s film talks about cohabitation, it asks that we all try to coexist without destroying one another, no matter how extreme someone’s differences may be. It’s a profound message that uses science fiction when speaking about its themes, yet it’s delivered with more elegance and emotional potency than some films about transgender discrimination or racism might. Cailley never soapboxes or clarifies his real-world parallels; he trusts his audience to interpret his message. That’s the rewarding power of genre.

Help Keep Deep Focus Review Independent

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review