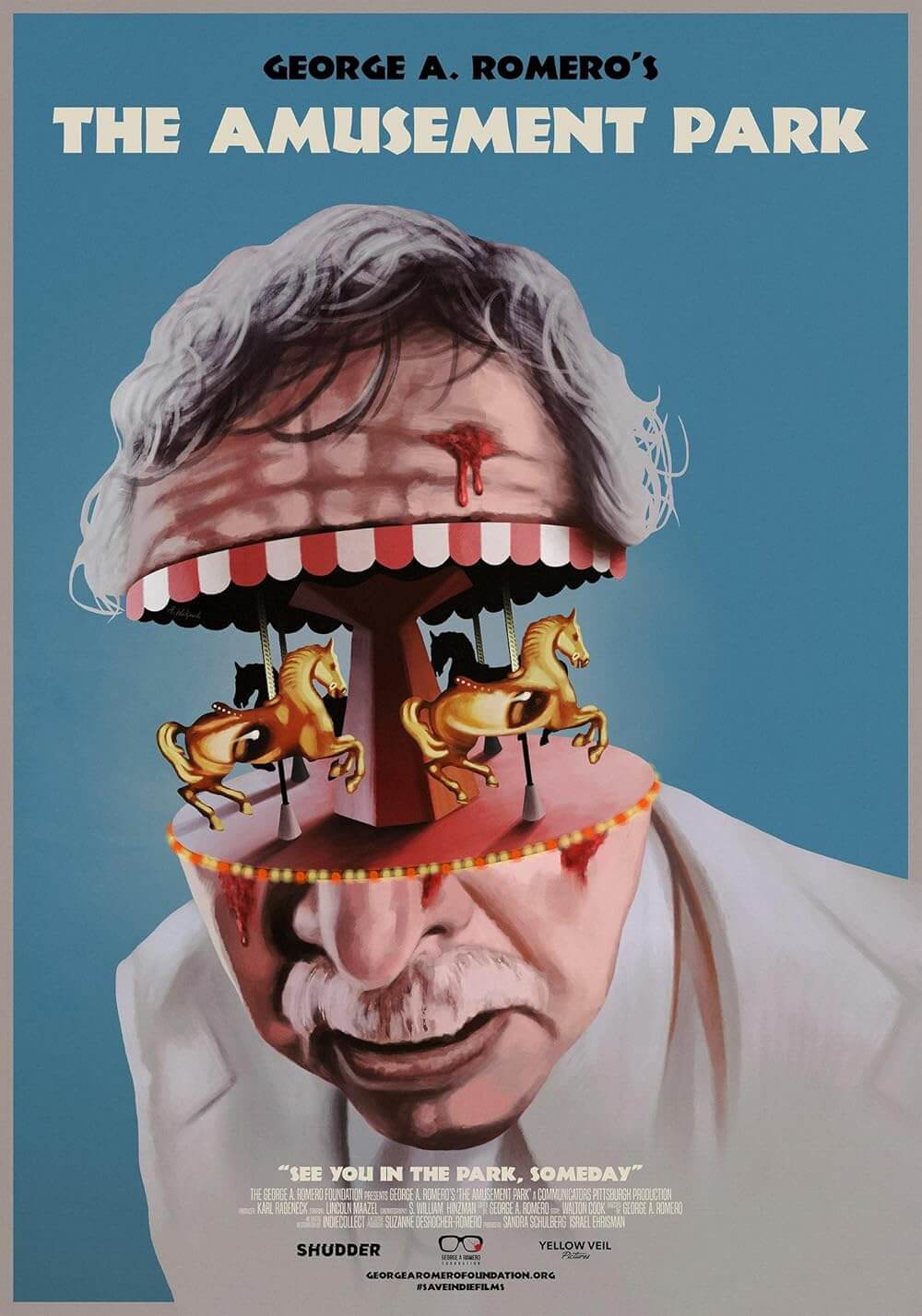

The Amusement Park

By Brian Eggert |

Since George A. Romero’s death in 2017, his widow, Suzanne Desrocher-Romero, has built up his legacy and helped legitimize his work beyond cult worship. She founded the George A. Romero Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to celebrating his life and filmography of horror classics, including Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978). The foundation arranges screenings, sets up scholarships, and even plans to launch a horror studies center at the University of Pittsburgh, Romero’s stomping grounds. Susanne is also developing his final zombie script, Twilight of the Dead, into a feature with a different director. Not long after his death, she uncovered The Amusement Park, which the Lutheran Society commissioned Romero to shoot. They wanted him to make a feature-length public service announcement that creates awareness about the rampant exploitation of elders and ageism in our culture. Unfortunately, when the group saw the film, they were appalled and refused to allow Romero to screen it. You might wonder what they expected from the guy who invented the modern zombie film.

After several years of restoration work by IndieCollect, The Amusement Park was screened on the Cannes Virtual Market and picked up for distribution on the arthouse circuit by Yellow Veil Pictures. The film, which runs a mere 54 minutes and tests the meaning of “feature,” debuts on the horror-centric streaming service Shudder as well. Romero’s fans will discover a film that has everything one might expect from a PSA, except with an unsettling sense of frankness about life as a senior citizen. It opens and closes with an actor, Lincoln Maazel, who also starred in Romero’s Martin (1977), addressing the audience directly. He explains that people in their elder years experience loneliness, failing health, poor nutrition, and no compassion from younger generations. This brand of discrimination, he explains, results in a denial of life’s pleasures to seniors. Finally, he warns, “Remember as you watch the film: One day you will be old.”

The film opens in a white room, where a battered older man (Maazel again) sits alone, breathing heavily in his filthy white suit. His hair slick with panicked sweat, his head marred with open wounds and bandages, he appears shaken and exhausted. Another identical man enters the room. The second man seems clean and unmolested, and he tries to comfort the distressed first man, offering to take him outside to the amusement park. The first man says, “There’s nothing outside,” and if the second man goes, he “won’t like it.” Regardless of the warning, the second man resolves to visit the park. Whatever he encounters out there, it’s evident from the outset, since Maazel plays both men, that the film will come full circle—the second man will go through the same traumatic experience as the first and end up back in the white room. The cycle is doomed to repeat itself, leaving those in their golden years to suffer alone in a void, forgotten and fearful of the outside world that has abandoned them.

Aside from the bookend scenes that outline the film’s thematic content, the material in-between at the park feels experimental. The surreal visuals and social metaphors play like Luis Buñuel’s nightmares, though filtered through Romero’s early 1970s style. Around this time, Romero was making Season of the Witch (1972) and The Crazies (1973), two films that commented on a society cracking at the seams. He used kinetic camera movements and sharply erratic editing to convey an increasingly chaotic and fragmented culture. Using that same aesthetic on The Amusement Park, Romero creates a disturbing portrait of old age. Shot in the long-closed West View Park, just north of Pittsburgh, he follows Maazel into a seemingly average park with rollercoasters, food stands, games, and even a freak show. Except, Romero distorts each to capture the humiliating and exploitative treatment of seniors.

Aside from the bookend scenes that outline the film’s thematic content, the material in-between at the park feels experimental. The surreal visuals and social metaphors play like Luis Buñuel’s nightmares, though filtered through Romero’s early 1970s style. Around this time, Romero was making Season of the Witch (1972) and The Crazies (1973), two films that commented on a society cracking at the seams. He used kinetic camera movements and sharply erratic editing to convey an increasingly chaotic and fragmented culture. Using that same aesthetic on The Amusement Park, Romero creates a disturbing portrait of old age. Shot in the long-closed West View Park, just north of Pittsburgh, he follows Maazel into a seemingly average park with rollercoasters, food stands, games, and even a freak show. Except, Romero distorts each to capture the humiliating and exploitative treatment of seniors.

Maazel’s unnamed senior enters the amusement park in his clean white suit, optimistic and kind. Then, a procession of encounters with grotesque characters and nightmarish vendors slowly eats away at his humanity: A pawn stand cheats seniors out of their antiques. Next, seniors must pass an eye exam to validate their driver’s license before riding in bumper cars. Even then, after an accident, a younger man blames a senior for his mistake, shouting things like, “The only thing stupider than an old driver is an old woman driver!” When he attempts to say hello to some kids, a man accuses him of being a “degenerate.” Maazel finds a priest who will graciously accept donations, but later on, when Maazel asks for help, the church closes its doors. A barker tries to sell him a retirement investment property (RIP), but the reality is an underserviced scam. Elsewhere, he’s horrified to discover the freak show places senior couples on display for a crowd that hurls insults and garbage at the people onstage.

The Amusement Park is one horrifying situation after another, each cutting into a different segment of our culture that ignores or dehumanizes seniors. Perhaps the most haunting episode involves a young couple who visit a fortune teller. They want to see the future, but the clairvoyant warns them, “You must see all.” The couple gets a glimpse of themselves decades in the future, when they must live on welfare in an apartment complex for impoverished seniors. Their landlord refuses to make repairs on their dilapidated building because his retired tenants cannot afford their rent, and their doctor refuses to come when the husband gets sick. Eventually, we return to Maazel’s character, who is robbed, then chased and beaten by bikers. His only pleasure comes at the day’s end, when a small child waves him over and asks him to read The Three Little Pigs. Before he’s finished the story, mother says it’s time to go. Maazel is left sobbing and alone, an image no one who’s ever impatiently rushed to end a visit with an older parent or grandparent will not soon forget.

Although there have been countless studies and articles about ageism, not to mention plenty of ongoing public debate, Romero’s film brought to mind comedian Albert Brooks’ debut novel, 2030: The Real Story of What Happens to America. Deadly serious, the story considers how a cure for cancer allows the senior population to spike, draining government resources that must be diverted from other programs to preserve the old. At the same time, younger generations, forced to support their elders financially, rebel by carrying out terrorist acts to eliminate the elderly and preserve a future for themselves. Brooks’ novel seems downright precognitive next to The Amusement Park, which manages to unnerve despite its brief runtime. As someone approaching 40, my gray hairs and occasional memory lapses signal that I’m quickly approaching irrelevance in my culture’s eyes. Will my generation become such a drain that it’s targeted for destruction? Or will I simply be deemed obsolete and fade away with a whimper?

The most disturbing scenes in The Amusement Park find Maazel walking through crowds, looking for help or human contact, though he goes wholly ignored. The film suggests what awaits in a few decades and how empathy now could make all the difference. Romero’s lost film is somewhere between a Kafkaesque allegory and a feverish nightmare. He warps the actual setting into a topsy-turvy location that works just as well as a social commentary as an unspeakably grim prediction of what’s to come. Although its full effect is somewhat spoiled when Maazel’s host once again addresses the audience in the final scene to summarize and explain what we’ve just seen, his last line is chilling: “I’ll see you in the park… someday.” It’s a terrifying reminder that the only thing that separates us from irrelevance is time.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review