Reader's Choice

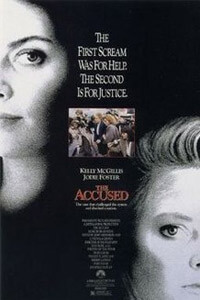

The Accused

By Brian Eggert |

The Accused confronts how victims often become the focus of rape trials. The 1988 film was the first Hollywood motion picture to plunge into the subject of rape, breaking down barriers to allow for a widespread discussion about victim-blaming and how rape is treated in the courts, the media, and society at large. Starring Kelly McGillis as a prosecuting attorney and Jodie Foster, in her first Oscar-winning role, as the victim of a brutal sexual assault by three attackers, it’s the rare film that considers the victim’s perspective. Countless other titles have centered on characters related to rape victims, such as the father of a victim in The Virgin Spring (1960), the husband in Straw Dogs (1971), and the mother in Eye for an Eye (1996). The entire rape-revenge subgenre often eschews the victim from their own story. However, The Accused raises questions about whether or not the victim’s attire, use of substances, or sexual history determines whether they deserved it—a notion that remains disturbingly commonplace in rape trials. It also shows the inadequacies of the American legal system to handle and supply justice for the victims of sexual assault. Perhaps most importantly, The Accused gives women a voice to tell their stories; although, its success remains questionable, as American culture continues to struggle with this nearly three decades after the film’s release.

A courtroom drama with a message, The Accused was loosely based the 1983 case of Cheryl Ann Araujo, a 21-year-old who was brutally gang-raped on a pool table by four attackers at a Massachusetts tavern, in front of onlookers who cheered and ignored her cries for help. Araujo received some justice, as her rapists received prison sentences, while the witnesses who encouraged the incident were acquitted. Tragically, she died a few years later in a car accident. The film, written by Tom Topor—a playwright whose previous film, Nuts (1987), dealt with a sex worker accused of murder—became a passion project for Dawn Steel, the president of production at Paramount Pictures at the time. Along with producers Sherry Lansing and Stanley Jaffee, Steel sought out Topor to write about Araujo’s case, despite grumbling from studio executives about the subject matter. The Accused would be ripped-from-the-headlines filmmaking, as several publicized stories of gang rape inspired Topor besides Araujo’s case. Among them was the rape and murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964, which reportedly had over thirty witnesses—leading to the bystander effect’s nickname, “Genovese Syndrome.”

The Accused was something altogether new. No film at the time had ever been made about rape, especially not with two women at the center. The filmmakers sought to explore how our society deals—and doesn’t deal—with these crimes. The film exposes the trend of investigators and defense attorneys blaming the victims of rape, and it labels cheering on a rape as a crime. Lansing told The Hollywood Reporter in their detailed oral history of the production, “I was obsessed with the culpability of the bystander and the double victimization of people who were raped. Not only was there the crime, but then they were victimized again with this idea that they deserved it.” But there’s an even more disturbing reality embedded into The Accused. Topor’s well-researched script reveals the necessity of institutions that are built up around the sheer volume of rapes in America. When Foster’s victim in the film arrives at the hospital after being attacked, there’s a team prepared, with nurses photographing the scratches and bruises on her body, taking vaginal swabs, combing for hair, and ready with mouthwash. A counselor from a rape center arrives to help her. The film barely emphasizes how horrifying it is that so many sexual assaults occur to require this level of organization as a response.

The Accused was something altogether new. No film at the time had ever been made about rape, especially not with two women at the center. The filmmakers sought to explore how our society deals—and doesn’t deal—with these crimes. The film exposes the trend of investigators and defense attorneys blaming the victims of rape, and it labels cheering on a rape as a crime. Lansing told The Hollywood Reporter in their detailed oral history of the production, “I was obsessed with the culpability of the bystander and the double victimization of people who were raped. Not only was there the crime, but then they were victimized again with this idea that they deserved it.” But there’s an even more disturbing reality embedded into The Accused. Topor’s well-researched script reveals the necessity of institutions that are built up around the sheer volume of rapes in America. When Foster’s victim in the film arrives at the hospital after being attacked, there’s a team prepared, with nurses photographing the scratches and bruises on her body, taking vaginal swabs, combing for hair, and ready with mouthwash. A counselor from a rape center arrives to help her. The film barely emphasizes how horrifying it is that so many sexual assaults occur to require this level of organization as a response.

The film opens just moments after the rape of Sarah Tobias (Foster), who runs screaming from a dive bar called The Mill. She’s processed for evidence and photographed in a hospital room with an alarming lack of privacy (there’s a window looking out at other nurses and patients). Then she meets Kathryn Murphy (Kelly McGillis), the assistant district attorney who asks her questions about her alcohol and marijuana usage, her criminal record, her motivations for going to the bar, and what she wore that night. “How you dress can make those guys think they can have sex with you,” Sarah is told. We see that Sarah is asked more questions than the rapists, whom she is forced to identity when Kathryn, accompanied by police officers, returns with her to the scene of the crime only a few hours later. The lack of consideration for Sarah is staggering in these scenes, and it only continues. Kathryn sees Sarah as nothing but trailer trash, a poor waitress interested in astrology. She has a hot temper, an unpolished way of speaking, and lives with a crummy boyfriend—the type of guy who, after learning about the rape, says “I wish I knew what to say,” and a few days later “When are you gonna get over this?” The choice to make Sarah a difficult person to like is a bold one; it’s a challenge to our empathy that, ultimately, helps prove the film’s point that no one deserves to be raped.

Topor’s script also deals with judicial standards and patriarchal power, as Kathryn, the hardened prosecutor, does not fully sympathize with Sarah’s situation at first, and the men in charge care nothing about Sarah receiving justice. Kathryn’s boss (Carmen Argenziano) instructs her to “make a deal and put ‘em away,” even if the charge is reduced to “reckless endangerment” with a maximum sentence of five years (9 months with good behavior). And so Kathryn, accustomed to how rape cases usually play out, makes the deal. But the choice robs Sarah of the chance to tell her story in court. Only after Kathryn learns about the crowd of onlookers, and is confronted with what happened to Sarah, does she pursue a “criminal solicitation” charge against those who cheered the rapists on—in spite of warnings from her disapproving male boss that she’ll either look like an “incompetent” or a “vengeful bitch” for filing charges against the spectators. Though she eventually shows empathy for her client and pursues justice out of moral responsibility, there’s not much to Kathryn’s character. She’s a surrogate for the audience, navigating how the system does not give much clemency to rape victims. As Kathryn, and the film, begin to recognize the toll of Sarah’s rape, the problems with the system become evident.

Topor and director Jonathan Kaplan complicate matters in their eventual depiction of the rape. It’s shown in flashback as part of court testimony, but not from Sarah’s point of view. Another onlooker, a naive college boy named Ken (Bernie Coulson), the same witness who called 9-1-1 and reported the rape, gives his smoking-gun account that eventually convicts the three locals who watched and encouraged the crime. It’s a choice that reminds one of Tootsie (1982), which had a troublesome way of explaining the plight of women through a man’s perspective. In effect, the jury only believes what happened to Sarah when Ken explains it. Therefore the film both exposes and plays into the problem that values a man’s testimony over a woman’s. It also shines a light on college rape culture—in a scene of fratboys congratulating their rapist friend, named Bob Joiner (Steve Antin) no less—even as it requires a fratboy to bring Sarah justice. But then, the need to listen to women feels peripheral to The Accused. It’s briefly hinted at when the defense attorney (Peter Van Norden) questions why Sarah only said “no” as she was being raped, and not “help” or “police”—as if her single-word protest somehow gives consent.

Topor and director Jonathan Kaplan complicate matters in their eventual depiction of the rape. It’s shown in flashback as part of court testimony, but not from Sarah’s point of view. Another onlooker, a naive college boy named Ken (Bernie Coulson), the same witness who called 9-1-1 and reported the rape, gives his smoking-gun account that eventually convicts the three locals who watched and encouraged the crime. It’s a choice that reminds one of Tootsie (1982), which had a troublesome way of explaining the plight of women through a man’s perspective. In effect, the jury only believes what happened to Sarah when Ken explains it. Therefore the film both exposes and plays into the problem that values a man’s testimony over a woman’s. It also shines a light on college rape culture—in a scene of fratboys congratulating their rapist friend, named Bob Joiner (Steve Antin) no less—even as it requires a fratboy to bring Sarah justice. But then, the need to listen to women feels peripheral to The Accused. It’s briefly hinted at when the defense attorney (Peter Van Norden) questions why Sarah only said “no” as she was being raped, and not “help” or “police”—as if her single-word protest somehow gives consent.

The gang rape scene may last just three minutes, but it feels much longer. It’s excruciatingly protracted and painful to endure, not only given what it shows but how Kaplan and company decided to film it. Seeing the rape through Ken’s eyes, the camerawork by d.p. Ralf Bode watches as Sarah performs a drunken dance in the bar’s game room, ogling her just as the growing crowd of men does. The scene’s use of the gaze remains confused and uneven. One of them, Danny (Woody Brown), starts kissing her, and she pushes him away. A moment later, he has lifted her onto a pinball machine and torn off her underwear. Danny holds her down, covers her mouth, and begins to rape her. Several men begin howling and goading others to join in. There is some reluctance on the part of Kurt (Kim Kondrashoff), and in a disturbing flourish, the film almost seems to have sympathy for how he’s peer-pressured into raping Sarah. Briefly edited into this scene, which again is told from Ken’s recollection, are a few momentary POV shots from Sarah’s perspective, revealing the nightmarish scene from her eyes. It hardly feels adequate.

The filmmakers labored over how to shoot this scene, and their attention aside, it’s both confronting yet suspect in its use of subjectivity. Using Ken’s vantage point, which seems to transition from his initial allure to eventual horror, may have been the wrong choice—especially when considering that another witness, Sarah’s waitress friend Sally (Ann Hearn), could have supplied more objectivity or at least occupied a woman’s view. Then again, when Sally leaves the scene, the film underscores how many women remain uncomfortable with acknowledging or fighting against the gendered culture of rape. In any case, the filmmakers reportedly edited this scene in several different ways. Lansing told The Hollywood Reporter about the first cut of the film: “At the test screenings, we got the lowest scores in the history of Paramount. The audience thought that Jodie’s character deserved the rape.” Paramount executives were looking for a reason not to release the controversial film, but after the filmmakers re-edited the picture, The Accused received much higher preview scores. Upon its release into theaters, the film earned $32 million in box-office receipts, as well as positive critical notices.

But not unlike the confused rape scene, there’s evidence throughout The Accused that it was workshopped in the editing room. Note the mid-film scene, before Kathryn gains a conscience, that might be its most cathartic. Sarah is confronted by one of the onlookers, Cliff (Leo Rossi), at a record store, and he proceeds to harass her, mocking her for being raped and blocking her from leaving the parking lot with his pickup truck. She responds by ramming his vehicle with her car, a symbolic act to be sure. But it’s a moment that never comes out in the court case, nor does it factor into Kathryn’s argument as proof that Cliff saw what had happened, thus it feels oddly situated in the film. Similarly, several close-up shots of Sarah’s personalized license plate (SXY SADI) indicate that it may be used in court, or at least have greater relevance than it does, but it’s hardly mentioned again, making the emphatic shot seem strange. Were there trimmed scenes where the defense attorney asked about this in court? Moments such as these suggest that The Accused is not tightly wound filmmaking, but it’s effective nonetheless.

But not unlike the confused rape scene, there’s evidence throughout The Accused that it was workshopped in the editing room. Note the mid-film scene, before Kathryn gains a conscience, that might be its most cathartic. Sarah is confronted by one of the onlookers, Cliff (Leo Rossi), at a record store, and he proceeds to harass her, mocking her for being raped and blocking her from leaving the parking lot with his pickup truck. She responds by ramming his vehicle with her car, a symbolic act to be sure. But it’s a moment that never comes out in the court case, nor does it factor into Kathryn’s argument as proof that Cliff saw what had happened, thus it feels oddly situated in the film. Similarly, several close-up shots of Sarah’s personalized license plate (SXY SADI) indicate that it may be used in court, or at least have greater relevance than it does, but it’s hardly mentioned again, making the emphatic shot seem strange. Were there trimmed scenes where the defense attorney asked about this in court? Moments such as these suggest that The Accused is not tightly wound filmmaking, but it’s effective nonetheless.

The film feels both dated and painfully relevant today. The score by Brad Fiedel has a corny after school special quality, accentuating its status as a message film from the 1980s. But even after more than 30 years, the subject matter still resonates—which is to say, our culture has only moderately improved in its treatment of rape victims. Not until the #MeToo movement has real progress been made. Certainly, the conviction of Harvey Weinstein for a first-degree criminal sexual act and third-degree rape, which landed him a 23-year prison sentence, brings justice to a rapist who flourished under a cloud of silence for decades. Even so, there’s a long history to overcome concerning the stigma and reluctance to talk about rape. It took making this film for McGillis to come forward about her own attack at the hands of two young men, one of whom received three years in prison, and the other was acquitted. Ironically, McGillis’ choice to come forward on the press tour for The Accused was criticized at the time, and her role as Kathryn Murphy would be one of her last high-profile roles. She had gone from working alongside Harrison Ford and Tom Cruise in Witness (1995) and Top Gun (1986) to roles in obscure horror films and a life of teaching. One cannot help but wonder if Hollywood had blamed the victim for speaking out.

Kaplan’s career was filled with middlebrow offerings, including yuppie thrillers like Project X (1987), Unlawful Entry (1992), and Brokedown Palace (1999). A highlight in his filmography, The Accused stands out because it tackles a subject that other mainstream filmmakers refused to address at the time, while his directorial choices often feel misguided or questionable. Fortunately, the film boasts an unflinching performance by Foster (under an awful wig after her character chops off her hair), whose career had floundered since her breakout on Taxi Driver (1976). Foster had even considered giving up acting before she won her Oscar for this role. But The Accused is not without its appeal as a courtroom melodrama in which the bad guys receive their comeuppance and the crowd feels like justice has been done. Complaints about the visual execution and patchwork editing notwithstanding, there’s rarely a moment where the viewer isn’t invested in Kathryn’s moral journey or Sarah’s fight to be heard and believed. One only wishes its message would have had a greater impact on the culture at large.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your continued support, Avshalom!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review