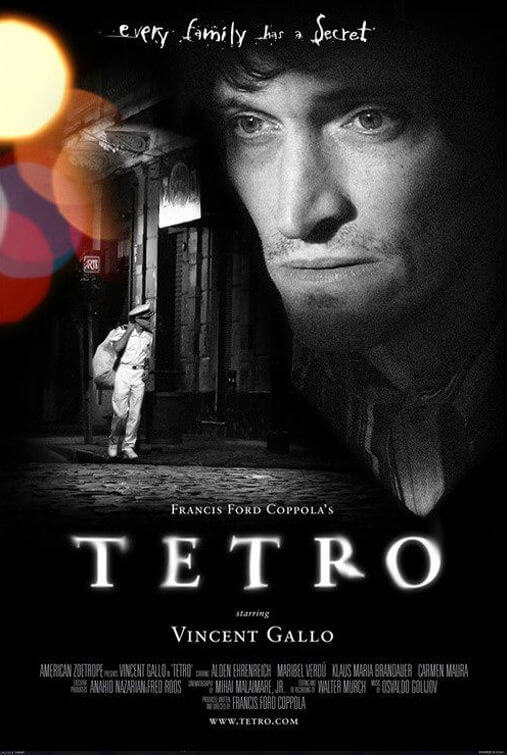

Tetro

By Brian Eggert |

Francis Ford Coppola’s illustrious career in the 1970s produced some of cinema’s most monumentally artistic motion pictures. Not only The Godfather and its sequel but benchmark titles like The Conversation and Apocalypse Now. His career fell into obscurity over the next several decades, however, as his production company, American Zoetrope, struggled to secure financing on a number of projects. Forgettable movies like The Cotton Club were interspersed with technical marvels like Bram Stoker’s Dracula. And after the underwhelming and tragically disappointing release of Youth Without Youth in 2007, the filmmaker’s future seemed uncertain.

Shot with a master’s sense of craft in beautiful black-and-white photography, Coppola’s latest film, Tetro, rekindles narrative motifs he hasn’t explored since his heyday in the 1970s. Much like The Godfather, the arty and melodramatic tale follows a man desperate to escape his family, while simultaneously he cannot avoid his connection to them. And though the thematic elements of Coppola’s greatest films are evident here, his new effort lacks the sense of truthful dramatic grandeur for which he’s often celebrated. The production exudes airs that suggest a young, independent director has just escaped film school to put everything he learned to use. Inspired though it may be, it’s also an indulgent and transparent bore.

Nearly 18, Bennie (Alden Ehrenreich) arrives in Buenos Aires to find his emotionally maligned older brother, Angelo (Vincent Gallo), who left their family after a falling out with their famous composer father, Carlo (Klaus Maria Brandauer). Angelo has rejected his past and family, changing his name to “Tetro” as an abbreviation of their surname, Tetrochini. He now shares a flat with his understanding psychiatrist-turned-girlfriend Miranda (Maribel Verdú), and reluctantly, he allows Bennie, who venerates his older brother, to stay with them. An aspiring writer who was supposed to produce a masterpiece but never did, Tetro has pages of unfinished writings in code, which Bennie finds, decodes, completes, and produces as a play. Therapy for both Tetro and his brother, the play is acted out on stage, serving up equal parts admiration and contempt for the adage that life imitates art, and vice versa.

The film harbors significant autobiographical notes for Coppola, whose own father Carmine played in the NBC Symphony Orchestra and later became a composer, writing the scores for Apocalypse Now and The Outsiders. And just like Carlo in the film, Carmine had a musically inclined brother, who also married a dancer, who provided significant competition. Where Coppola elaborates is the drama involved, using his family trials as an influence for a pointedly more provocative—but not more engaging—result. Despite echoing his own family’s resentment toward artists, he fails to create a resounding emotional connection with the audience.

Attribute this failing to Gallo, independent cinema’s ever-brooding, takes-himself-too-seriously actor and sometimes director. The scowling features and penetrating eyes of this actor display much on the surface but fail to break through into the needed emotionalism of the character, whether the role is that of a tortured writer or not. Meanwhile, Ehrenreich does wonders playing a role that has to be naïve, curious, and yet reeling on the inside from a desperate lack of self-identity. If only these two actors were matched in their ability to draw sympathy from the audience. Either way, what little sympathy does filter onscreen is spoiled by the overtly symbolic—and, compared to what came before it, uncharacteristic—finale.

As with most Coppola films, whether failures or not, the result is irresistibly watchable and even admirable from the standpoint of pure craftsmanship. His cinematographer Mihai Malaimare Jr. captures some gorgeous compositions that might make enduring the ordeal justified. Truly, Tetro is worth your time, if only to see how Coppola is experimenting these days. But this is also an extravagant, bawdy, decadent art film—the director goes so far as to imitate ballet scenes from Powell and Pressburger’s The Tales of Hoffman, even if audiences are hungry for something pure and classical Coppola again. Seeing this film, it becomes evident that the Francis Ford Coppola of The Conversation and The Godfather no longer exists, and that he was replaced by someone who doesn’t care if he drags his audience through a filmic mess of self-indulgence.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review