Reader's Choice

Terminator 2: Judgment Day

By Brian Eggert |

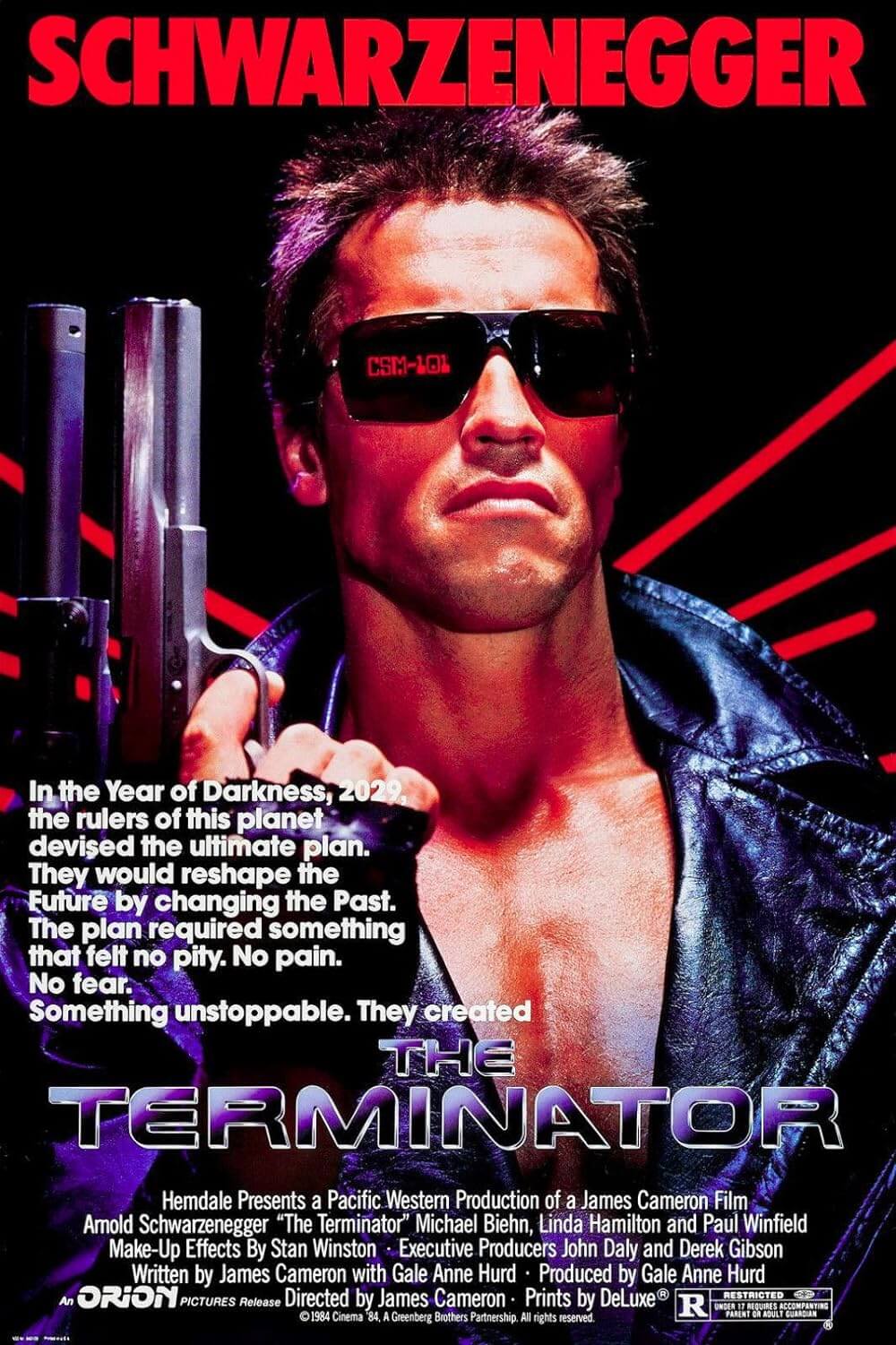

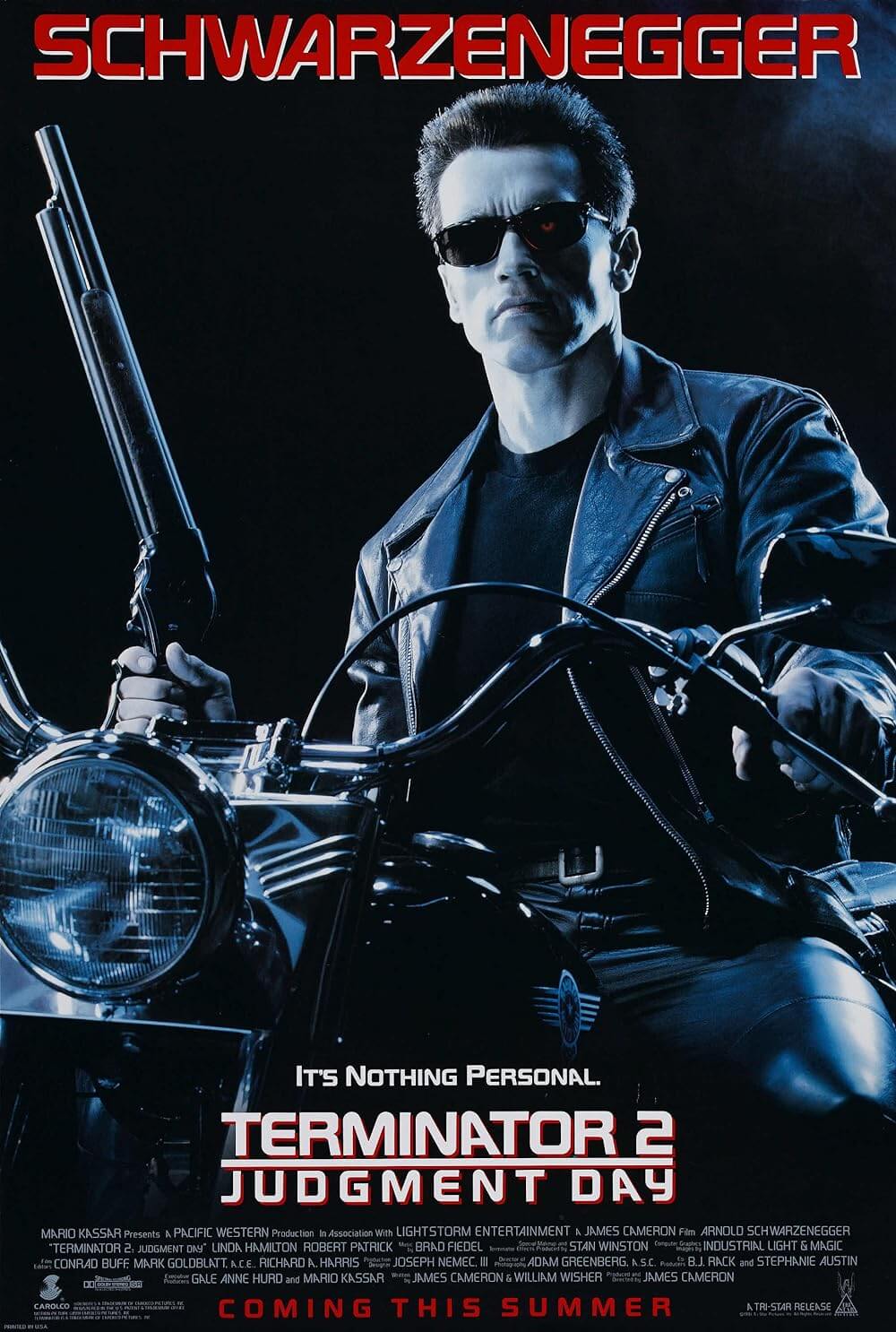

When it debuted in 1991, Terminator 2: Judgment Day blew the collective minds of action movie junkies and, well, everyone who enjoys movies. What size this production has, what innovation, and what crowd-pleasing excitement. Marked by its breakthrough special effects, an unending series of bravura action sequences, and clever narrative inversion of the 1984 original, the production sells itself: Arnold Schwarzenegger, then at the height of his popularity, plays the good guy this time around, protecting the future’s rebel leader, John Connor, played by newcomer Edward Furlong. Linda Hamilton committed to her transformation into a ferocious survivalist and earned Oscar buzz for her performance. The new CGI technology renders an iconic movie villain, played by Robert Patrick, composed of liquid metal. And director James Cameron, in his prime after Aliens (1986) and The Abyss (1989), takes the scope far beyond what he achieved in the first, offering unexpected emotional value on top of his breakneck spectacle. T2 was the most expensive film ever made then, and it outperformed all box-office projections. This would be a trend for Cameron, which he would repeat with Titanic (1997) and his Avatar films. In its day, there was hardly a film more talked about or at the forefront of the zeitgeist than T2, and it would change the way blockbusters were made for the foreseeable future.

And yet, despite its many technical advancements, grosses upwards of half a billion, and lasting impact on the industry, T2 remains Cameron’s clunkiest script. On the level of pure pulse-pounding momentum, one cannot deny the film’s power. But the sequel lacks the edge of The Terminator, and amid its inconsistent narration and kid-friendly appeal, it feels compromised. Indeed, Cameron made consolations for T2. An audience of young viewers had seen The Terminator on cable television and VHS, and when social critics decried the film’s violence and Schwarzenegger’s popularity in the youth culture of the 1980s, Cameron responded by softening the sequel. While still rated R, the T-800 does not terminate; it protects. “I think of it as a violent movie about peace,” Cameron told Newsweek. Worse, Cameron’s desire to appeal to young people with his message leaves T2 marked by dreadful early 1990s signifiers that feel painfully forced upon revisitation. Consider the Bart Simpson-like phrases of the young John Connor, such as “No problemo” and “Hasta la vista, baby,” which serve as the film’s comic relief and way of appealing to youngsters, or the nonsensical humor (“I need a vacation,” the T-800 quips). More inspired is Cameron’s ingenious idea to make the T-1000 look like an L.A. cop, a prescient choice after the world was rocked by footage of Rodney King’s beating by the LAPD a few months before the sequel’s release in July 1991.

After The Terminator debuted to unexpected box-office success, Schwarzenegger pushed Cameron to make a sequel, but rights disputes with the original producers at Hemdale Film Corporation and Cameron’s lack of interest stalled a follow-up. Mario Kassar’s Carolco Pictures—which had released Schwarzenegger starrer Total Recall in 1990—wanted to make the sequel, and Schwarzenegger convinced Kassar to buy the rights no matter the cost. After Kassar’s $10 million purchase, he had to convince Cameron to make a sequel. Cameron wasn’t interested until Kassar offered him a $6 million dollar payday. Suitably motivated, Cameron and William Wisher began writing and completed their draft in May 1990. Cameron drew from an early version of the original 1984 screenplay, which contained a liquid metal terminator, an idea Cameron scrapped because special effects technology could not adequately represent the character. But after using CGI to depict water-based formations in The Abyss, Cameron’s liquid metal idea now seemed possible. With a massive $70 million budget that eventually ballooned to $100 million (the original’s cost was just over $6 million), the production began shooting the following October; it lasted until March of 1991, with much time spent on its Oscar-winning special effects and CGI implementation. The film would make $204 million at the US box office alone, becoming the year’s top earner; it was an unprecedented success on home video as well and developed an instant legacy for its epic action sequences.

Cameron’s initial disinterest in the production and payday mindset upon accepting the job comes through in what might be his most by-the-numbers script. In story structure terms, the basic outline follows its predecessor almost exactly. If it had been released today, Terminator 2: Judgment Day might even be called a reboot of the franchise, aside from its numeric title. Just as Cameron repeated several elements from Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) while also deepening the mythology in his sequel, Aliens, the director duplicated several themes from The Terminator and expanded on them by adding layers to his basic outline, resulting in its case of sequelitis. Consider the parallels between the two films: In each, two time-travelers, one bad and the other good, return to fight over John Connor’s eventual rebellion against the supercomputer Skynet. Someone is deemed crazy (by the same psychologist, the snide Dr. Silberman, played by Earl Boen) for their belief in Judgment Day. The Terminator says, “I’ll be back,” almost as if delivering the line exclusively to gratify the viewer. And then, in the industrial plant finale, all evidence of time-traveling robots is disposed of, quite conveniently. Despite these parallels to The Terminator, the story is tweaked just enough in T2 to keep it interesting, with the similarities written off as dramatic irony. These moments wink at the audience. So, too, do the sequel’s more nonsensical callbacks to the original. Early on, when the T-800 takes sunglasses from a Hell’s Angels biker, it’s only so Schwarzenegger can replicate the Terminator’s look from the first film for the viewer’s delight—a look the character adopted to conceal its damaged eye. Here, the choice has no purpose except to appease the audience.

Cameron’s initial disinterest in the production and payday mindset upon accepting the job comes through in what might be his most by-the-numbers script. In story structure terms, the basic outline follows its predecessor almost exactly. If it had been released today, Terminator 2: Judgment Day might even be called a reboot of the franchise, aside from its numeric title. Just as Cameron repeated several elements from Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) while also deepening the mythology in his sequel, Aliens, the director duplicated several themes from The Terminator and expanded on them by adding layers to his basic outline, resulting in its case of sequelitis. Consider the parallels between the two films: In each, two time-travelers, one bad and the other good, return to fight over John Connor’s eventual rebellion against the supercomputer Skynet. Someone is deemed crazy (by the same psychologist, the snide Dr. Silberman, played by Earl Boen) for their belief in Judgment Day. The Terminator says, “I’ll be back,” almost as if delivering the line exclusively to gratify the viewer. And then, in the industrial plant finale, all evidence of time-traveling robots is disposed of, quite conveniently. Despite these parallels to The Terminator, the story is tweaked just enough in T2 to keep it interesting, with the similarities written off as dramatic irony. These moments wink at the audience. So, too, do the sequel’s more nonsensical callbacks to the original. Early on, when the T-800 takes sunglasses from a Hell’s Angels biker, it’s only so Schwarzenegger can replicate the Terminator’s look from the first film for the viewer’s delight—a look the character adopted to conceal its damaged eye. Here, the choice has no purpose except to appease the audience.

The sequel opens with rebellious 10-year-old John Connor, whose biological mother Sarah is now locked up in a mental institution, raving about Judgment Day—supposedly coming in 1997, when the artificially intelligent defense system Skynet wipes out most of humanity by launching a nuclear attack. A liquid metal-based Terminator, dubbed T-1000, which can morph its body into blades and change its appearance at will, sets out to kill John, the eventual resistance leader against Skynet’s army of machines. In a role reversal, the film places the now-archaic T-800 in the hero role to protect John from the T-1000. John learns that the Terminator must obey his orders, and he has some fun with that. Then, together, they break Sarah out of the asylum. Once they regroup and arm themselves, they resolve to stop Skynet at the source, enlisting Cyberdyne Systems engineer Miles Dyson (Joe Morton, exuding humanity in his few brief scenes) to help them stop Skynet before his company builds it. During the raid, the T-1000 shows up, and a chase ensues. Meanwhile, the Terminator becomes John’s father figure and friend, leading to a sad end when, after disposing of the T-1000 in a metal works, the heroic cyborg asks Sarah to lower it into the vat of molten steel, removing all evidence of Terminators from the timeline.

While one could discuss the story more thoroughly, it’s best not to look too closely. This yarn unravels upon close inspection, beginning with another temporal paradox at the center. The Terminator introduced a temporal paradox by suggesting that Sarah’s protector, Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn), traveled back in time to father John. In T2, without the Terminator from the first film going back in time and leaving a robotic arm and computer chip behind, Cyberdyne would have never developed the microprocessor necessary to create Skynet. (To recap linear temporal theory, time is sequential and moves in a forward line until altered by time travel, so Dyson would’ve had to invent Skynet without the benefit of Terminator leftovers initially.) So the question is a familiar one—which came first, the chicken or the egg? Therein resides the temporal paradox of this series and the unsatisfying way Cameron explores it. But why bother complaining about holes or vaguely explored notions in Cameron’s application of science fiction? Cameron is more concerned about the wowing sequences than his characters, and he establishes their motivations just enough to justify the action.

Away we go from the moment the Terminator rescues John at a mall through a series of massive multi-vehicle chases involving dirt bikes, semi trucks, tanker trucks, motorcycles, helicopters, and everything in between. Cameron has always excelled at building momentum and not slowing down until the end credits. His showmanship is legendary, his capacity for orchestrating mayhem unparalleled. And Terminator 2: Judgment Day is a prime example. His plotting thrusts the action into motion, and before the viewer knows how much time has passed, the film is over—quite a feat, considering its two-and-a-half-hour runtime. However, Cameron owes a large debt of gratitude to George Miller’s The Road Warrior (1981) for this sequel, as several car chase sequences seem directly inspired by those in Miller’s film. For example, Cameron borrows the notion of one last bullet tumbling onto a moving car, and someone having to climb out to get it, from Miller’s sequel. Though, along the way, there’s far less death than in the original, as John teaches the Terminator that mindless killing is wrong. As a result, several police officers receive bullets in their kneecaps instead of in the head.

Away we go from the moment the Terminator rescues John at a mall through a series of massive multi-vehicle chases involving dirt bikes, semi trucks, tanker trucks, motorcycles, helicopters, and everything in between. Cameron has always excelled at building momentum and not slowing down until the end credits. His showmanship is legendary, his capacity for orchestrating mayhem unparalleled. And Terminator 2: Judgment Day is a prime example. His plotting thrusts the action into motion, and before the viewer knows how much time has passed, the film is over—quite a feat, considering its two-and-a-half-hour runtime. However, Cameron owes a large debt of gratitude to George Miller’s The Road Warrior (1981) for this sequel, as several car chase sequences seem directly inspired by those in Miller’s film. For example, Cameron borrows the notion of one last bullet tumbling onto a moving car, and someone having to climb out to get it, from Miller’s sequel. Though, along the way, there’s far less death than in the original, as John teaches the Terminator that mindless killing is wrong. As a result, several police officers receive bullets in their kneecaps instead of in the head.

Other reprieves from the action arrive in tender moments between characters, with many reinserted into the extended Special Edition of the film released on various home video formats. For instance, the T-800 only learns because John and his mother operate on the cyborg’s head to alter its “CPU neural net processor,” a scene cut from the theatrical version. This detail better establishes the Terminator’s curiosity and capacity to learn from John, for the Tin Man to develop a heart. The Special Edition also better shows Dyson as a family man. The 15 minutes of additional footage includes scenes of comic relief when John attempts to teach the T-800 to smile, resulting in a goofy bit of physical comedy from Schwarzenegger. Elsewhere, Sarah dreams of Reese while in the asylum, where he appears and urges her to protect John, reminding her that the future remains open with the speech John made him memorize: “There is no fate but what we make for ourselves.” These moments feel essential to the story structure and humanity of the characters, and they generally improve upon the theatrical version.

Looking back, the sequel boasts a career-best performance for Hamilton, who agreed to return on the condition that Cameron make her “crazy.” The performer drew from her own experiences with mental illness and manic depression to give Sarah her unbalanced edge. She trained with ex-Israeli commando Uzi Gal for a year to achieve the physicality and weaponry know-how for her fiery performance. But it’s also a rather tragic turn. When finally faced with stopping Judgment Day by killing Dyson, she cannot go through with it despite her haunting dreams of a bleak future she has never seen. And about those dreams—these are strange details since Sarah has only been told about Judgment Day during her brief time with Reese. Her imagination, coupled with a mental breakdown, seems to have filled in the blanks quite vividly. Regardless, Hamilton goes beyond the limitations of her waitress-turned-warrior role from the original, and her best scenes occur in the asylum, where she clashes with the predatory staff and mounts an escape attempt before her son and his new guardian rescue her. However, Sarah’s voiceover is a clunky device, conveying her fear of Judgment Day, her apprehension toward the Terminator’s relationship with John, and in the end, her optimism for an uncertain future. But structurally, it’s odd to have Sarah narrate the story since the narrative and filmmaking generally follow John’s point of view for most of the movie, whereas Sarah’s presence feels tertiary.

The real protagonist of T2 is John Connor, at least for the first two-thirds, and casting him was arguably the biggest risk of the production. Furlong, a streetwise kid the casting director found at a Boys and Girls Club in Pasadena, had the naturalism and attitude required for the part. His father was unknown, and his mother was gone; an uncle raised him. With plenty of real-life parallels, Furlong does well in the role, though Cameron’s dialogue for John and understanding of children leaves much to be desired. But it’s the relationship between the boy and the cyborg that Cameron sought to get right—modeled after similar dynamics in Shane (1953) and Old Yeller (1957), where the boy forms a companionship before eventually losing said companion. Cameron wanted to bring the audience to tears over the loss of what was previously a killing machine, but he doesn’t quite hit the mark. When the T-800 remarks, “I know now why you cry,” before getting lowered into molten steel amid John’s protests, only to flash a thumbs up, the response isn’t tears but cringe. Whereas Cameron often achieves a pitch-perfect balance of sentimentality and action—evidenced in Aliens, The Abyss, and Titanic—T2 falters in its earnest ambitions.

The real protagonist of T2 is John Connor, at least for the first two-thirds, and casting him was arguably the biggest risk of the production. Furlong, a streetwise kid the casting director found at a Boys and Girls Club in Pasadena, had the naturalism and attitude required for the part. His father was unknown, and his mother was gone; an uncle raised him. With plenty of real-life parallels, Furlong does well in the role, though Cameron’s dialogue for John and understanding of children leaves much to be desired. But it’s the relationship between the boy and the cyborg that Cameron sought to get right—modeled after similar dynamics in Shane (1953) and Old Yeller (1957), where the boy forms a companionship before eventually losing said companion. Cameron wanted to bring the audience to tears over the loss of what was previously a killing machine, but he doesn’t quite hit the mark. When the T-800 remarks, “I know now why you cry,” before getting lowered into molten steel amid John’s protests, only to flash a thumbs up, the response isn’t tears but cringe. Whereas Cameron often achieves a pitch-perfect balance of sentimentality and action—evidenced in Aliens, The Abyss, and Titanic—T2 falters in its earnest ambitions.

While many scenes from the sequel would become ingrained into 1990s pop culture, T2 is most remembered for how its Oscar-winning special effects changed Hollywood. Earlier examples of shape-shifting in Willow (1988) and liquid formations in The Abyss were mere testing grounds for how Industrial Light and Magic animated one of cinema’s most memorable movie villains—aided by Patrick’s sharp, intentional performance. ILM’s Dennis Muren spent about the budget of The Terminator to accomplish the CGI in T2, though it amounts to just five minutes of footage. Even so, what’s most impressive about the production is how many practical, old-school effects Stan Winston’s studio used. Most of its car chases, motorcycle stunts, and explosions would be entirely CGI today, as would the bullet holes and other damage inflicted on the T-1000. But the blend of CGI and practical effects demonstrated here, and further perfected in Jurassic Park in 1993, render a more convincing visual experience than today’s default mode of overreliance on CGI. Apart from a moment or two—the T-1000 summersalt roll out of a tanker truck, for instance—the sequel still looks incredible.

Considering the director’s stated ambitions for Terminator 2: Judgment Day, if Cameron hoped to instill a theme about the necessity for peace, the theme doesn’t register. When violence looks this good, this groundbreaking, this thrilling, it’s difficult to ignore the adrenaline rush and extract a lesson about the necessity for peace. But, similar to its predecessor, Cameron implants a warning about the dangers of technology and artificial intelligence. References to Skynet have become shorthand for the threat of AI gaining sentience and attacking humanity, but that hasn’t stopped computer scientists from developing similar technology. Whatever its intended lessons, it’s best to think of Terminator 2: Judgment Day as an engaging, impressive action movie laden with moments of melodrama and schmaltz. The unmeasurable amount of mayhem onscreen remains impressive, leaving its ideas to be an afterthought. But it’s more significant for other reasons, such as its technical advancements in filmmaking, its continued waves in the culture, and Cameron’s ability to conceive and execute amazing action sequences.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on March 3, 2024.)

Bibliography:

Cornea, Christine. Science Fiction Cinema: Between Fantasy and Reality. Rutgers University Press, 2007.

Keegan, Rebecca. The Futurist: The Life and Films of James Cameron. Three Rivers Press, 2009.

Nathan, Ian. James Cameron: A Retrospective. Palazzo Editions, 2012.

Plagens, Peter. “Violence in Our Culture,” Newsweek, 1 April 1991, pg. 46.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review