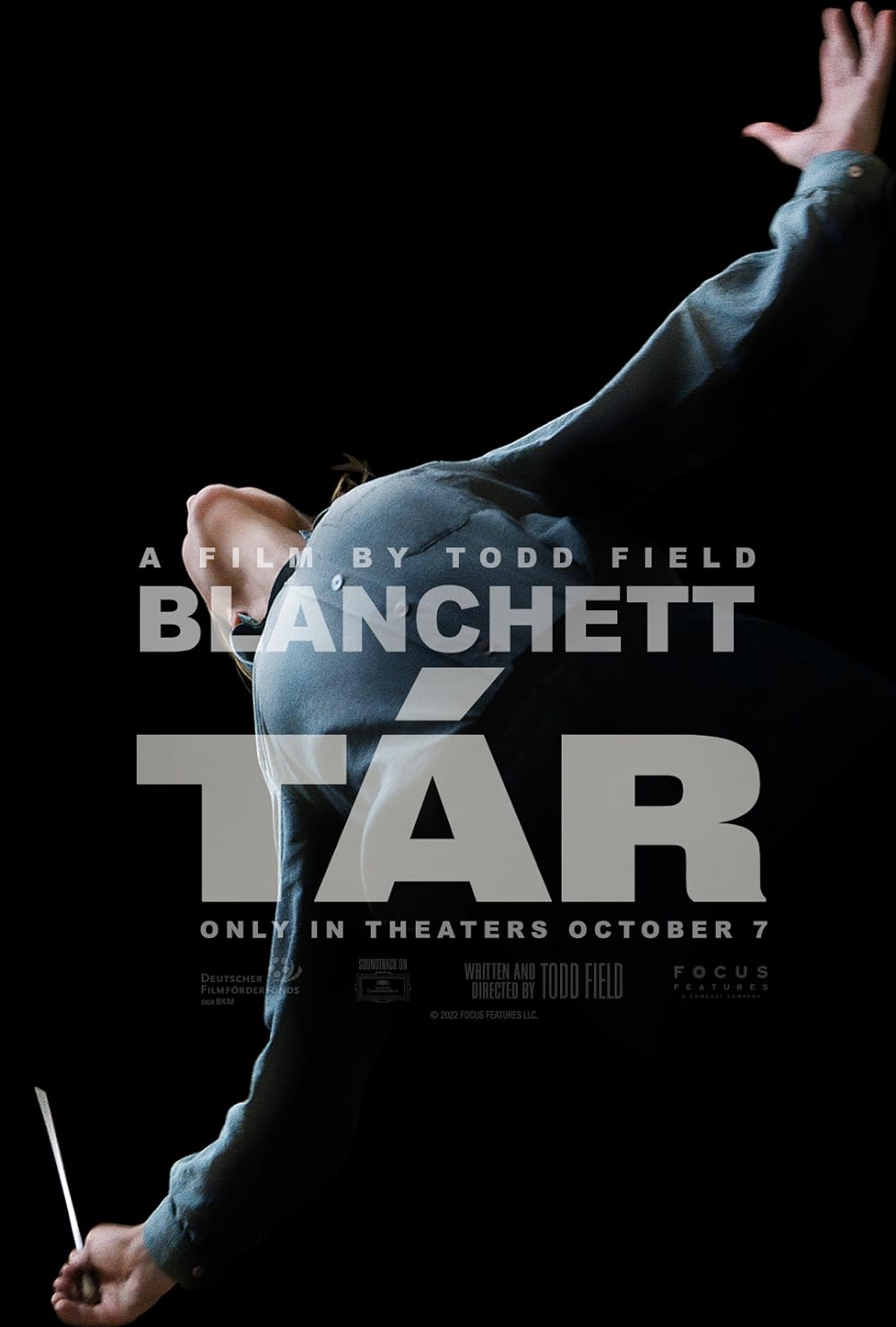

TÁR

By Brian Eggert |

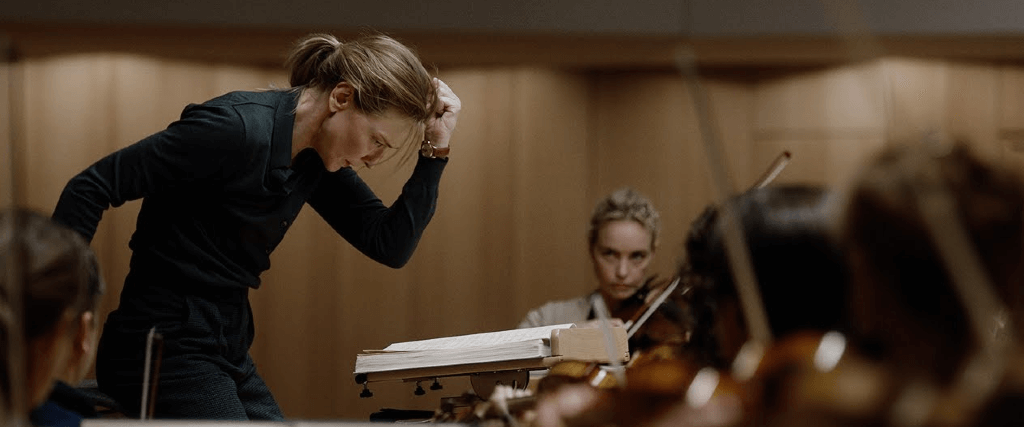

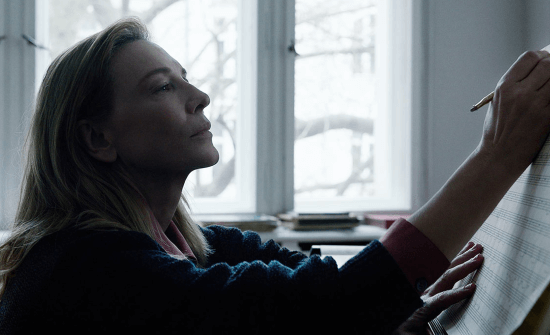

Todd Field’s TÁR is an examination of power. It opens with a shot of someone—we don’t see who—recording Lydia Tár, played by Cate Blanchett, a world-famous conductor and among the few women to head a major orchestra. Lydia is sleeping, but contemptive messages about her go back and forth between two unknown parties. As a lesbian in a male-dominated sphere, her rise is unprecedented, yet she holds her position full of awareness and self-satisfaction about the power she wields. That’s part of the problem. Field’s film unfolds as an immersive character study, and Blanchett delivers another virtuoso performance that leaves much to the viewer. TÁR asks that we recognize the systems one must maneuver to access power and how, in some cases, talent alone won’t do the trick—one must understand politics and people and how to exploit them. It asks that we see power as a corrupting force and, therefore, a responsibility. When a scandal emerges around Lydia, the film also asks that we consider how power comes with scrutiny and how those without power will seize upon it. Without making statements or reinforcing moral edicts or sociopolitical positions, Field investigates the truth about those with power and how they abuse it. Ever interested in flawed people, Field’s cinematic discussion results in one of the most complex films of 2022, one both of the moment and timeless in its themes.

TÁR is only the third film by Field, whose last effort, Little Children, came out 16 years ago. Before that, he helped invent Big League Chew (yes, really), performed as a jazz musician, and dabbled as an actor, taking minor roles in big movies such as Twister (1996) and The Haunting (1999). He also memorably played the piano player who tells Tom Cruise about the secret orgy in Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999). But in the early 2000s, Field stopped acting and turned to directing. First, he bowed the domestic drama In the Bedroom (2002), a passionately acted film with a moment of violence so shocking that it leaves a permanent scar on the viewer’s mind. Little Children followed, testing whether his audience could empathize with some challenging characters, including two adulterers (Kate Winslet, Patrick Wilson) and Jackie Earle Haley’s Oscar-nominated turn as a pedophile. Both films show Field’s absolute composure and mastery of the filmmaking craft, willingness to explore entangled subjects, and literary approach to cinema in how he asks his audiences to read and interpret his work.

TÁR is no exception. After Field’s long absence from the film scene, his third feature reaffirms his status and justifies the last 16 years of critics and audiences wondering why he had disappeared and lamenting that he hadn’t completed another film. Though Field has been attached to various projects over the years—including an adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and a thriller co-written by Joan Didion—his sudden reappearance with an original story feels urgently contemporary. The film is entrenched in the music world with almost documentary-like observations of rehearsals and performances. It moves with the escalating pace of a slow-burning psychological thriller, though it never steps into that territory fully. At times, it even feels darkly comic, recalling Paul Thomas Anderson’s look at oilman Daniel Plainview, where the monstrosity on display is so potent that it’s almost funny. Field manages these various tones with expert precision, relying on long takes, austere cinematography by Florian Hoffmeister, and a measured control worthy of comparison to Kubrick.

An early scene in TÁR features Adam Gopnik, writer for The New Yorker, interviewing Lydia before an audience. Before taking the stage, he introduces her as “one of the most important music figures of our time” and details her résumé as a veritable cult of personality in the music world. She received a Ph.D. from Harvard and studied under her mentor, Leonard Bernstein, who instilled in her a need to uncover the composer’s intention. Her career has taken her from the prestigious orchestras in Cleveland, Boston, and New York to her current and most distinguished post, the Berlin Philharmonic. She has genius-level talent, knows her history of composers, and has performed a major ethnographic study of tribal music in Peru. She also received the Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony Awards, making her an EGOT. Now she’s finalizing work on a book, Tár on Tár, and she’s preparing a new recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 5—the only Mahler symphony Lydia hasn’t yet interpreted in her role as a self-described “human metronome.” But as Gopnik lists her accomplishments, the viewer watches Lydia backstage, enacting a routine of preparatory gestures, physical and aural ticks, and pill popping that suggests a complex inner life.

An early scene in TÁR features Adam Gopnik, writer for The New Yorker, interviewing Lydia before an audience. Before taking the stage, he introduces her as “one of the most important music figures of our time” and details her résumé as a veritable cult of personality in the music world. She received a Ph.D. from Harvard and studied under her mentor, Leonard Bernstein, who instilled in her a need to uncover the composer’s intention. Her career has taken her from the prestigious orchestras in Cleveland, Boston, and New York to her current and most distinguished post, the Berlin Philharmonic. She has genius-level talent, knows her history of composers, and has performed a major ethnographic study of tribal music in Peru. She also received the Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony Awards, making her an EGOT. Now she’s finalizing work on a book, Tár on Tár, and she’s preparing a new recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 5—the only Mahler symphony Lydia hasn’t yet interpreted in her role as a self-described “human metronome.” But as Gopnik lists her accomplishments, the viewer watches Lydia backstage, enacting a routine of preparatory gestures, physical and aural ticks, and pill popping that suggests a complex inner life.

Field never over-explains Lydia, despite listing her accomplishments. Instead, he presents a case, considers her subjectivity, and acknowledges the circumstances of her rise. An outsider in a traditionally patriarchal vocation, Lydia admits during a guest lecture at Julliard that one must “obliterate yourself” on the conductor’s stand. This process allows the conductor to have a point of view about the music but also conform to the composer’s vision and make it relatable. This doesn’t register with a queer, nervous-kneed BIPOC student who won’t appreciate a white cisgender artist such as Bach. What follows is an engaging debate that Lydia escalates and shuts down sharply when it becomes passionate and insulting. The scene is characteristic of many in TÁR, where Lydia uses her authority to control the conversation. At the same time, the film understands how a woman of her age and sexuality had to make compromises, ultimately destroying a part of her identity to gain her status in the establishment. If she did not embrace the masters, develop a tough skin, and deny herself to some extent, she might never have achieved her current position or notoriety. It’s at once a tragic, pragmatic, and troublesome detail that exposes how systems of power flourish and subtly change over time, and how art usually evolves through pastiche and adaptation.

Meanwhile, Lydia maintains several personal relationships, and power dynamics define most. A fellow conductor, Elliot Kaplan (Mark Strong), yearns to have her talent, but over lunch, she dismissively tells him to “do your own thing,” which is impliedly beneath her. Lydia’s beleaguered assistant, Francesca (Noémie Merlant), has ambitions to become a conductor as well, and she both admires Lydia’s talent and detests her sense of superiority. In Berlin, Lydia lives with Sharon (Nina Hoss), the orchestra’s first violinist, and occasionally gaslights her. They have a young daughter, Petra (Mila Bogojevic), of whom Lydia is fiercely protective. Lydia’s apparent love of Petra is endearing if clouded by her volatility, especially in a scene where she confronts Petra’s bully on a playground, warning in perfect German, “I will get you.” When Lydia’s behavior becomes a public matter later, Sharon confronts her about how their romance, and indeed all of Lydia’s relationships, began as “transactional”—a means of Lydia moving up in Berlin with the intention of a studied tactician. Still, her affection for Petra is genuine; she’s free to love her because she doesn’t need anything from her.

TÁR spends much of its 158-minute runtime detailing Lydia’s behaviors, from her sensitivity to rogue noises (a doorbell sound, a clicking pen) to her labeling dissenters as “robots.” Doubtless, when she studies history’s composers whose lives were often tumultuous and whose behaviors vile, there’s a flash of recognition. Indeed, she is supremely charismatic but also manipulative, obsessive-compulsive, and dangerously sure of herself. After a musician and former lover named Krista commits suicide—an incident for which she appears mostly unsympathetic and quick to put behind her—Lydia’s pattern of grooming and seducing up-and-coming talent comes into question. She has already tried to cover her tracks by asking Francesca to delete all emails related to Krista. And she has already selected another target: an expressive young Russian cellist, Olga (Sophie Kauer), whom she advances in the orchestra in an unorthodox and ultimately predatory gesture that does not go unnoticed by all. They might even have become lovers had Lydia not become the subject of a cancel-culture scandal. By then, any hope of trying to understand Lydia becomes hopeless in a black-and-white debate.

TÁR spends much of its 158-minute runtime detailing Lydia’s behaviors, from her sensitivity to rogue noises (a doorbell sound, a clicking pen) to her labeling dissenters as “robots.” Doubtless, when she studies history’s composers whose lives were often tumultuous and whose behaviors vile, there’s a flash of recognition. Indeed, she is supremely charismatic but also manipulative, obsessive-compulsive, and dangerously sure of herself. After a musician and former lover named Krista commits suicide—an incident for which she appears mostly unsympathetic and quick to put behind her—Lydia’s pattern of grooming and seducing up-and-coming talent comes into question. She has already tried to cover her tracks by asking Francesca to delete all emails related to Krista. And she has already selected another target: an expressive young Russian cellist, Olga (Sophie Kauer), whom she advances in the orchestra in an unorthodox and ultimately predatory gesture that does not go unnoticed by all. They might even have become lovers had Lydia not become the subject of a cancel-culture scandal. By then, any hope of trying to understand Lydia becomes hopeless in a black-and-white debate.

Field pulls off something miraculous with TÁR—he balances its terrifically artistic formal presentation with timely subject matter that never panders to the audience. It’s accessible but never trite. His filmmaking is so ordered and perfectly tuned that it’s almost invisible, and his intricate character construction requires more analysis than can be achieved in a single review. To be sure, Blanchett delivers a performance with the majesty, sophistication, and, later, the shattered identity that earned her an Oscar for Blue Jasmine (2014). And much like the aforementioned There Will Be Blood (2007) character, Lydia is cruel in a way that draws us toward her and compels us to understand her, as opposed to turning us away. The only reservation about Blanchett’s presence is that it may overshadow the less outward performance by Hoss—who has starred in so many great films by German director Christian Petzold—so much of which relies on her eyes. Kauer, an actual cellist who plays her performances onscreen, is also a powerful presence.

TÁR has already proved evasive and left audiences debating its message. Is it a treatise supporting cancel culture or an accounting of a #MeToo takedown? Does it suggest these so-called cancellations go too far and end any hope of healthy debate? Field raises questions but never offers answers. For all of Lydia’s awful behavior, Field also questions the online culture that operates with a mob mentality, thinking in polarized extremes. Even as TÁR explores abuses of power, Field doesn’t rob Lydia of her humanity once her power is taken away. Instead, Field forces us to consider Lydia’s formation through the history and establishment of art, her use of power in personal and professional relationships, and whether her extraordinary art should be celebrated in the wake of her behavior. In the film’s final scenes, Field also recognizes that art doesn’t lose its power just because of how someone lives their life. Even so, TÁR is fascinating because it refuses to judge or wholly villainize Lydia, nor does it confirm the audience’s reaction. So many films today take political action by reinforcing a belief and preaching to the converted. Field and Blanchett have something trickier in store: a film that operates as a prompt and encourages what will hopefully become a productive discussion.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review