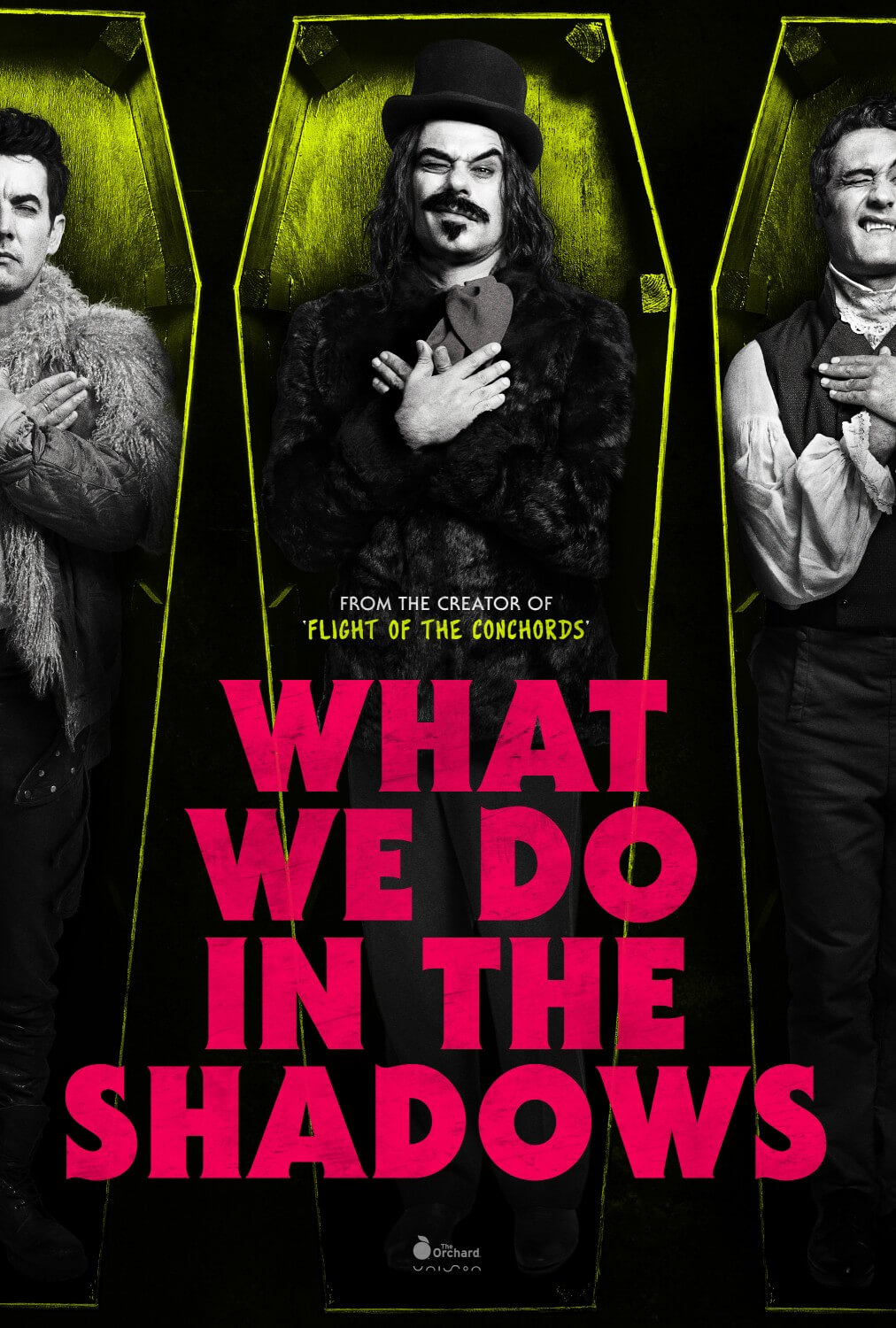

Tales from the Hood

By Brian Eggert |

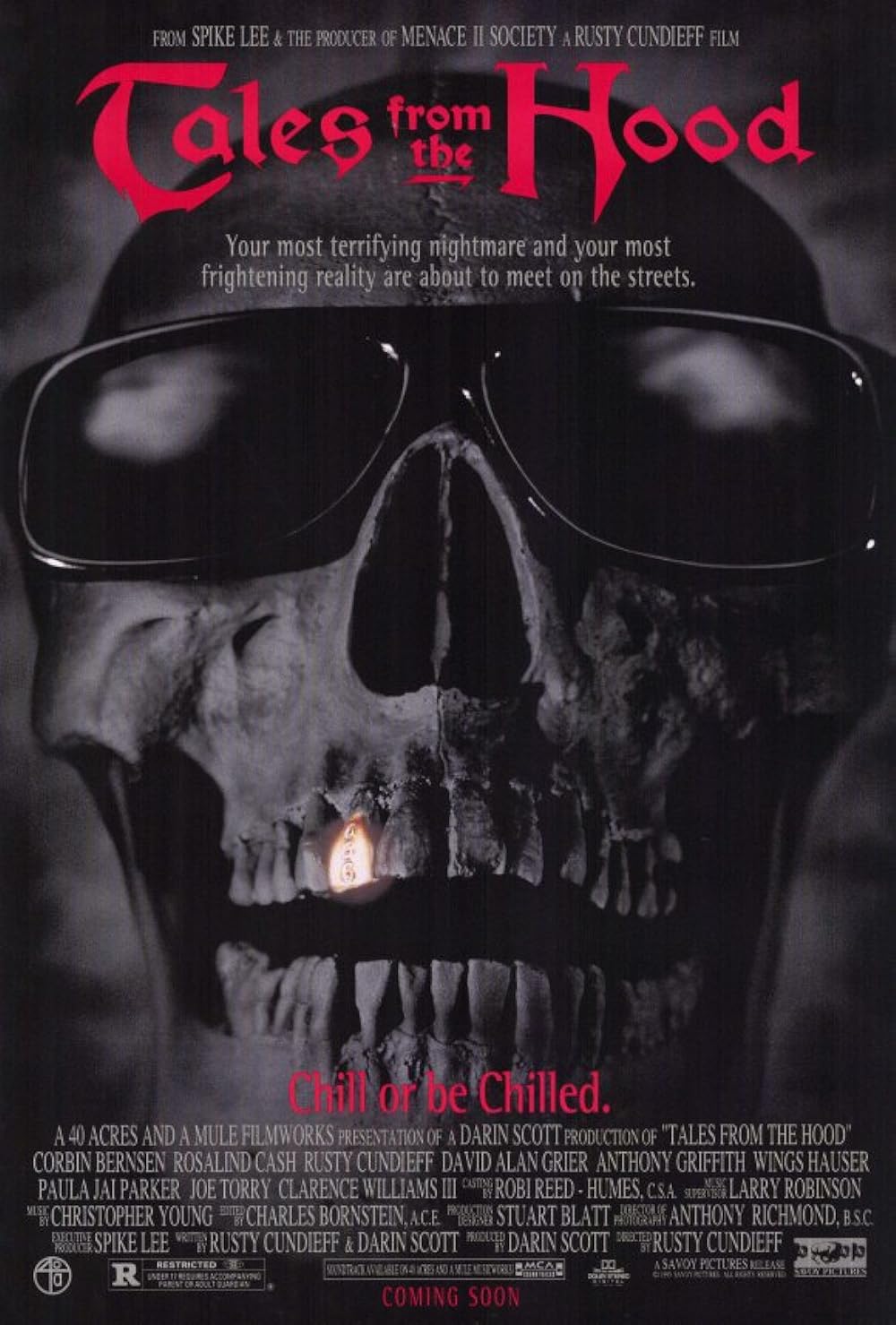

Horror anthologies usually have a structure that prevents them from feeling cohesive. The typical format brings together several filmmakers, and each director contributes one segment among many, which are interwoven through a connecting story. Though each segment may follow an overarching theme, some stories will inevitably prove better than others. The visual styles and tones may vary as well, leaving one or two stories more accomplished and the overall production uneven. Perhaps that’s why portmanteaus seldom last in the memory as a whole, aside from this or that segment. In rare cases like 1995’s Tales from the Hood, a single filmmaker creates a thematically and aesthetically consistent film that, like any other anthology, has highs and lows, but it contains a throughline that resonates. Director Rusty Cundieff and his co-writer Darin Scott use the format to create a gory piece of genre entertainment. Yet, they craft stories about crooked and racist police officers, domestic abuse, slavery, white supremacist politicians, and gang violence. In each macabre tale, Cundieff reconsiders the past through a new method of evaluation and representation, using grim horror stories to capture a glimpse of modern and historical reality.

At once a B-movie lark and a vital text that feels even more relevant today, Tales from the Hood came out of the commercial horror heyday of the 1990s. It follows in the tradition of Tales from the Darkside, the CBS series that ran from 1983 to 1988, and bowed an excellent anthology movie in 1990. It also draws from HBO’s popular Tales from the Crypt series, which blended humor and grisly special FX with death puns galore, and which also moved from television to cinemas with Demon Knight (1995) and Bordello of Blood (1996). Cundieff’s film shifts the focus away from the predominantly white horror stories of the era—Scream (1995), I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997), Urban Legend (1998)—that revolve around suburban neighborhoods. These films embrace a subtext of moral punishment against their wayward characters, where the teen victims are punished for exploring sex, bullying, or some other crime, and find themselves facing the sharp end of a knife (or hook, axe, etc.). But as scholar Carol E. Henderson observed, Cundieff’s film recontextualizes “the basis for examining the unresolved issues of racism and self-hatred embedded in the African American urban experience” both in contemporary and historical reflection.

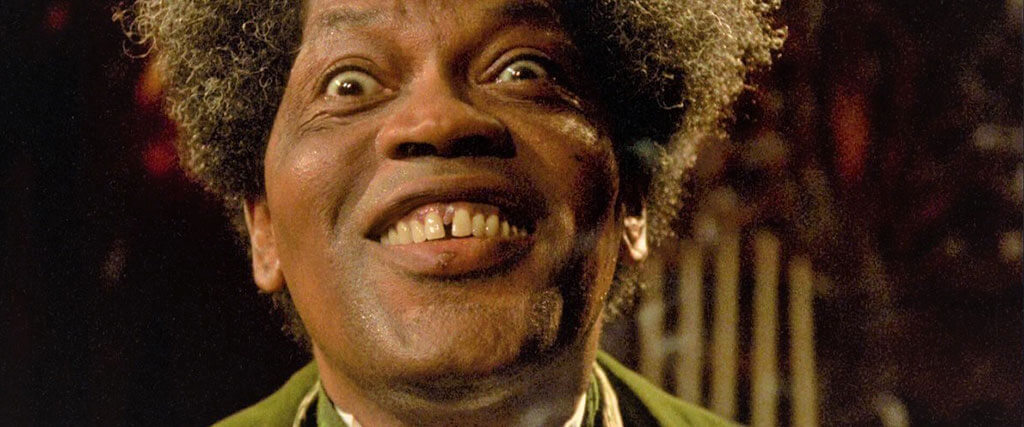

To be sure, Tales from the Hood’s moralizing quality intersects somewhere between the fantasized realm of horror and the continued trauma inflicted on people of color in the United States—“Where nightmares and reality meet on the streets,” according to the tagline. The wraparound tale follows three gang members (Joe Torry, De’Aundre Bonds, and Samuel Monroe Jr.) as they visit a funeral home operated by Mr. Simms (Clarence Williams III), whose manic eyes and Don King hair anticipate his mischievous behavior. Simms has found some missing drugs, and they have promised him some cash in exchange. But first, this veritable Crypt Keeper walks them through his mortuary, making stops at each coffin and telling a dark tale about how each person ended up inside. And from the outset, Cundieff confronts his viewer. The first story follows a rookie cop, Clarence Smith (Anthony Griffith), who witnesses his three white colleagues beat and murder a Black civil rights activist (Tom Wright) bent on eliminating police corruption. He keeps quiet according to the police officer’s code, but it tears him up inside over the course of a year. And even though the victim returns from the grave with Clarence’s help and exacts bloody vengeance, Clarence remains culpable for his silence. He ends up locked in a mental institution, though it’s not exactly clear how Simms got hold of him.

Simms’ stories each feature an other-worldly force reaching out to correct some wrong that occurs. In the second story, a young boy shows up to school with bruises. But the aggressor (David Alan Grier), dating the boy’s mother, receives his comeuppance when the child uses his drawing of the man like a voodoo doll to crumple him into a pile of twisted flesh. The third anecdote centers around a small wooden doll containing the soul of a former slave who, along with many others like him, was burned alive after the Civil War by a master who did not want to give them up. Corbin Bernsen plays a David Duke-esque political figure named Duke Metger, though today he uncannily resembles Donald Trump with his bad hair and fake tan. Metger, a one-time KKK member, sets up his campaign at a former plantation with a notorious history for slavery, and his behavior gets him eaten alive by the dolls of those burned—and not even the American flag, which he uses to shield himself, can protect him. The final tale follows the murderous Crazy K (Lamont Bentley), a gangster who refuses to repent, even after government-ordered experimental rehabilitation, even after being confronted by the ghosts of his victims. His lack of remorse is ultimately his undoing.

Cundieff targets racism and corruption in white circles of authority, from cops to politicians. At the same time, he also condemns Black-against-Black violence—whether it’s committed in a domestic space or through gang violence. A staggering sequence in the final story uses a juxtaposition of dramatized footage for Crazy K’s violent acts against actual photographs of lynchings. The violence that seemed cartoonish in the previous three stories becomes no laughing matter. Indeed, Tales from the Hood addresses disturbing cultural problems that can only end up in one place—the mortuary. Cundieff takes the moral didacticism even further in the conclusion, when Simms reveals (through laughable CGI and some underwhelming special FX) that he is Satan, and the three gang members who have listened to his stories will now suffer in Hell for their crimes against the hood. Even the opening title sequence, which reveals an ash-gray skeleton behind sunglasses and a gold tooth, holding a pistol and smoking a joint, implies that gangsterism and violence will only get you dead.

It’s surprising, actually, that Tales from the Hood is about something instead of another disposable (albeit entertaining) horror anthology. Fortunately, Cundieff doesn’t bog his film down in his message or resort to preachy statements; he and Scott have written memorable stories with engaging characters. Drawing inspiration from Trilogy of Terror (1975), The Twilight Zone, and A Clockwork Orange (1971), they weave their themes into an unlikely balance between humor, scares, and social commentary. On purely visual terms, the special effects throughout much of the production look impressive, aside from a few brief moments—and the worst of them comes in the last scene, threatening to derail the entire experience. Even so, the vivid cinematography by Anthony B. Richmond—who shot Don’t Look Now (1973), Candyman (1992), and Ravenous (1999)—and the playfully macabre score by Christopher Young give the production character.

With its themes about racial justice and accountability pulsing through each memorable segment, Tales from the Hood belongs on a shortlist alongside the best horror anthologies: Creepshow (1982), Trick ‘r Treat (2007), and Tales from the Darkside. Rather than a patchwork, it feels like a unified statement from a filmmaker who continued telling these stories (with diminishing impact) in two belated sequels in 2018 and 2020. Those dates should be evidence enough that it has taken moviegoers time to discover and appreciate Cundieff’s work, which was undoubtedly given a boost by the 2019 documentary, Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror. As audiences yearn for more diversity and representation in horror, Tales from the Hood should be remembered; it’s a rare piece of genre filmmaking that reflects today’s continued and urgent discussions about race in America.

Bibliography

Coleman, Robin R. Means. Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present. Routledge, 2011.

Guerrero, Ed. Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film. Temple University Press, 1993.

Henderson, Carol E. “Allegories of the Undead: Rites and Rituals in Tales from the Hood.” Folklore/Cinema: Popular Film as Vernacular Culture, edited by Sharon R. Sherman and Mikel J. Koven, University Press of Colorado, Logan, Utah, 2007, pp. 166–178. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt4cgnbm.12. Accessed 4 Oct. 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review