Tales from Earthsea

By Brian Eggert |

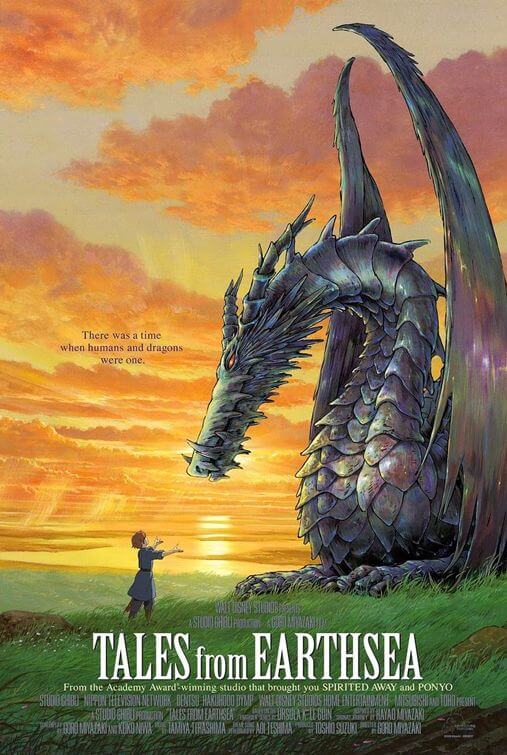

Goro Miyazaki, son of master animator Hayao Miyazaki, makes his directorial debut with Tales of Earthsea, an adaptation of Ursula K. Le Guin’s fantasy novels, primarily her third entry The Farthest Shore. Working under Japan’s leading animation house, Studio Ghibli, the younger Miyazaki delivers a gorgeous-looking piece of traditional hand-drawn animation, assisted by occasional bursts of computer animation for more complicated scenes. The painterly backdrops and detailed scenery are the highlights of an otherwise slow-moving narrative told in a staid, formal style deficient of humor or passion for the material. Though beautiful, it can feel impenetrable.

The opening scene features the assassination of a king by his troubled son. Arren, the prince, has some unknown force that he doesn’t understand growing inside of him, impelling him toward violence and hatred. He steals his father’s magic sword and makes for the countryside, where, after being cornered by a pack of wolves, he’s saved by an enlightened, mild-tempered wizard called Lord Sparrowhawk. The traveling wizard serves as Arren’s mentor, teaching him to survive and blend in, knowing that Arren will have a crucial role to play in the future. Sparrowhawk can feel that Earthsea is out of balance—that Nature’s scale has tipped to allow evil into the land. Familiar themes from Hayao Miyazaki’s work emerge here, including a great appreciation for the earth and a respect for what Nature has planned for us. Finding a temporary safe haven on a pastoral farm, Arren and Sparrowhawk form a makeshift family unit with the good witch Tenar and the young girl Therru tending fields and livestock.

Meanwhile, the androgynous villain Lord Cob seeks to defy Nature’s plan and achieve immortality, but to attain everlasting life he must learn the secret of Arren’s real name. Using his henchman Hare to gather up Arren to his castle, Cob attempts to manipulate the young hero into revealing his secret and also seeks to confront his old enemy Sparrowhawk. Much of the film’s mythology is communicated in a way that makes the viewer feel like an outsider, or that perhaps we’re missing something. Talk of “the balance” and the role of dragons in Earthsea remain unclear, whereas more basic themes of “good vs. evil” and facing your inner demons feel oversimplified in comparison to the untapped potential within the story. Ghibli has not announced plans to continue with future adaptations of Le Guin’s tales into animated features, however, which makes this film feel like the first chapter in an ongoing saga never to be completed.

Having opened in Japan in 2006, the film took its time getting to the U.S., as SyFy Channel owned the North American distribution rights for their ill-received miniseries based on the same material. After the film received some scathing reviews in Japan and a PG-13 rating, Walt Disney limited the theatrical release to only a few states and a handful of theaters, whereas the G-rated and well-reviewed Ponyo in 2009 was placed in some 800 theaters. Disney hired their standard celebrity voice actors to substitute the Japanese voicework, the standouts being Timothy Dalton as Sparrowhawk and a particularly effective Willem Dafoe as the hush-voiced Cob. Although, thankfully, the lovely song that plays over the film’s end credits remains in the original Japanese, even on the English soundtrack.

Devoted Le Guin fans aren’t likely to savor the adaptation, as Le Guin herself noted that while the character names and setting are taken from her books, the storylines share little in common. With its prevalent themes of naturalism over technology drawn from both Le Guin and classical Miyazaki family archetypes, Tales of Earthsea maintains a distanced tone that, unfortunately, leaves the experience feeling flat. Perhaps Le Guin’s epic world was simply too much for the rookie filmmaker, or perhaps Goro Miyazaki does not (yet) have the magical touch of his father. Still, it’s difficult not to admire how the intentionally measured pace plays out into the grand finale, even if the film leaves the audience feeling like there’s more to the story than we’ve seen, or will get to see. In any case, it becomes evident that Goro has much to learn, as the troubles here have more to do with his script than the animation. A father-son collaboration in the future, with Hayao writing and Goro directing, might resolve such inconsistencies and place the younger Miyazaki on the correct path.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review