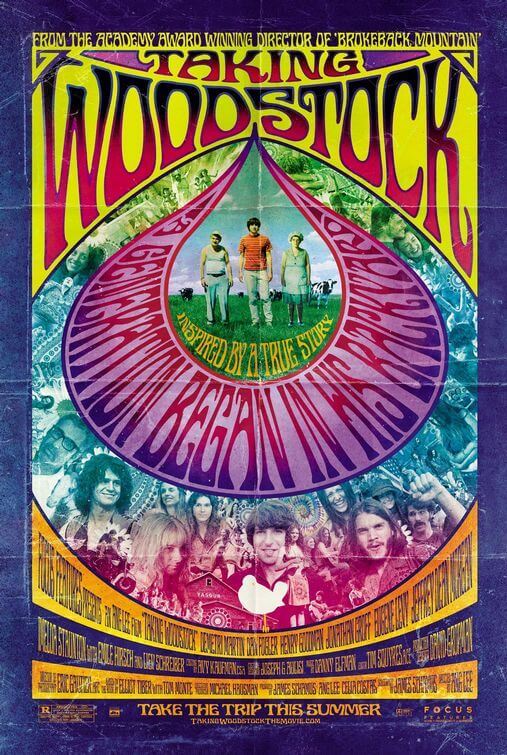

Taking Woodstock

By Brian Eggert |

Ang Lee’s Taking Woodstock is like having a backstage pass to the greatest concert in the world, but then you never see the music because you got lost on the way to the stage. What a bummer. Perhaps that’s the wrong way of looking at it since Lee clearly intended to make the behind-the-scenes hullabaloo of 1969’s iconic music festival into the main event of his film, all from the perspective of a young man looking to escape his family and stake his place in the world. But what this coming-of-age tale doesn’t do is overshadow the concert with its quaint backstory, even though it’s trying very hard to do so.

Here’s the problem: The film never shows us the concert. Not a single frame depicts Janis Joplin or Jimi Hendrix or The Who—in fact, we never see a musician at all. Danny Elman composed the score, and the soundtrack contains The Doors, who didn’t participate at Woodstock because Jim Morrison hated open-air venues. The closest we get is looking down upon the ocean of people from a distance, seeing only specks on the blurry stage, observing the glory of the show without understanding its meaning or participating through our viewership. So let’s pretend you know nothing about what this Aquarian Exposition means—since the script, written by Lee’s longtime collaborator James Schamus, doesn’t bother telling us—and concentrate instead on what we see.

Elliot Teichberg, played by dry-but-goofy standup comedian Demetri Martin, tries to make it as a painter and Greenwich Village interior designer. But his failure sends him back home to help manage his parents’ ramshackle motel in the Catskills. After preventing the bank from foreclosing on their “resort,” Elliot gets the bright idea to help out a parade of hippies, recently driven out of Woodstock, NY, by inviting them to the dairy cow fields of his hometown in White Lake. Having the local connections needed to get proper permits, Elliot finds himself overwhelmed by the influx of lawyers and longhairs behind the event, who all pay in cash. Suddenly, local business is booming; however, some of the less groovy folk don’t much care for hippies. “They’ll rape the cattle,” one farmer worries.

In no time at all, hundreds of thousands of people have gathered on the fields. Elliot’s parents, Jewish-Russian immigrants Sonia (Imelda Staunton) and Jake (Henry Goodman), take some guff for using their motel as a ticketing station. Still, any mob or anti-Semitic threats are quickly resolved—they’re a feisty old pair, plus they’ve got a transitioned volunteer security guard (Liev Schreiber) on their side. Elliot, meanwhile, announces in a press conference for the local paper that the concert is free; he was under the influence when he said it, but how were they going to check half a million tickets anyway? Still, Elliot’s parents have earned enough for a lifetime in ticket commissions; that doesn’t much matter to his mother, who refuses to let Elliot grow up.

Of course, Lee means for Elliot’s eventual rebellion to serve as some sweeping allegory for every attendee at the festival, as each person has their own message, be it anti-war protests, liberation through drugs, freedom of speech, and so on—all shown in a brief montage, shot with vintage cameras for an authentic period feel. In a very inconsequential way, when Elliot stands up against his parents, he represents how everyone at the concert makes a statement of some kind by being there. Lee’s ongoing theme of forbidden love, present in almost every one of his films, appears once more when Elliot realizes he’s gay about halfway through the film. We understand this conflict because we intrinsically know that a small town in the 1960s wouldn’t take a shine to no homosexual; however, Lee doesn’t make the conflict apparent by addressing it in, say, a confrontation with his parents or the townsfolk. It’s simply a discovery Elliot makes.

Imagine how much more powerful a mosaic of characters would be, all achieving the same level of independence through their presence at Woodstock, and how much more gratifying that would be for the otherwise accomplished lineup of actors, who do little more than serve their purpose here. But aside from plenty of acid trips, freeing nudity, and mud sliding, Lee avoids the concert altogether, making the universal aspect of a film about “3 Days of Peace & Music” (e.g., the music) almost entirely nonexistent. Luckily, a restored version of Michael Wadleigh’s excellent 225-minute documentary Woodstock from 1970 has just been released on DVD by Warner Bros., offering anyone interested in what really happened the multi-perspective view Taking Woodstock doesn’t offer.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review