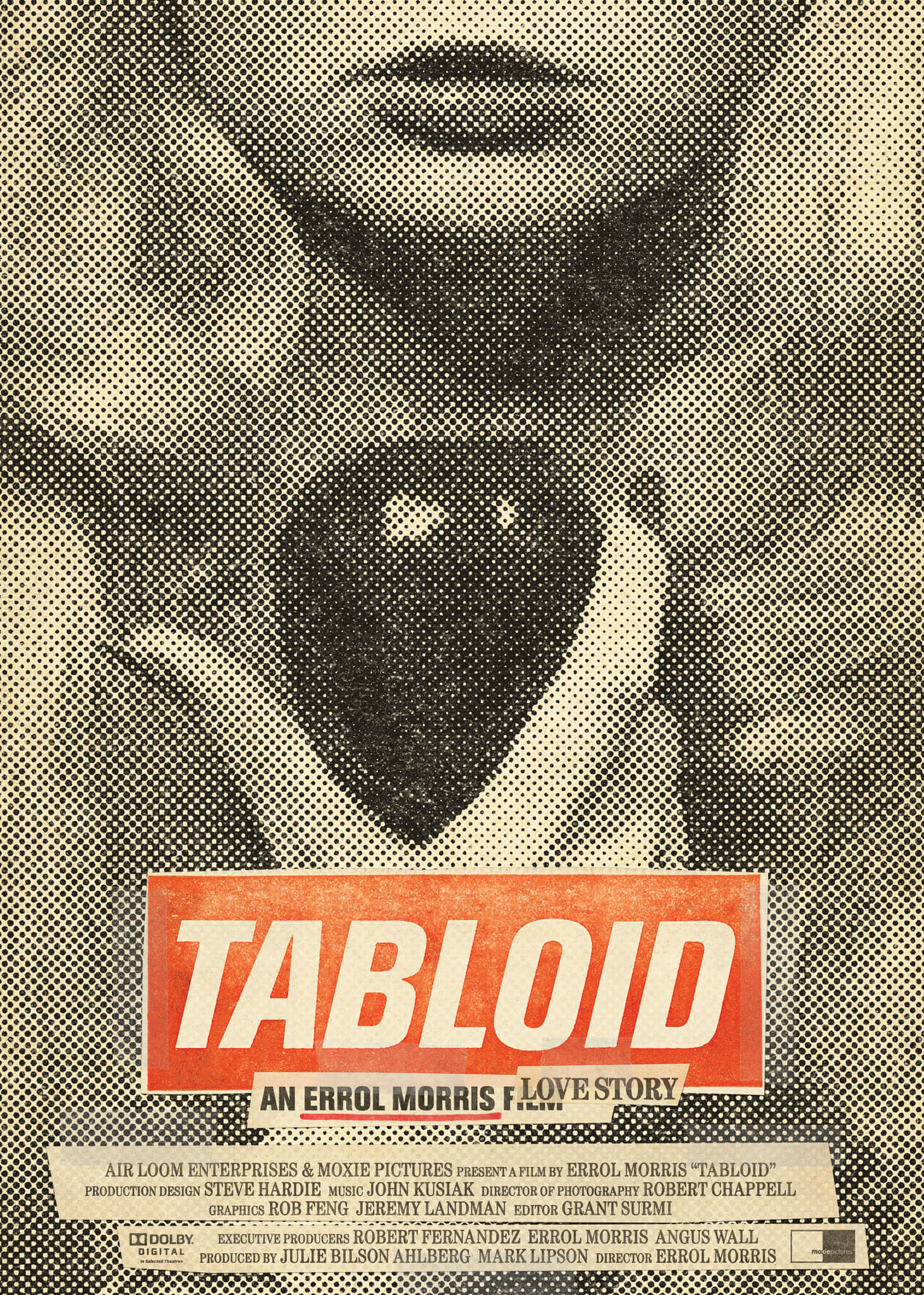

Tabloid

By Brian Eggert |

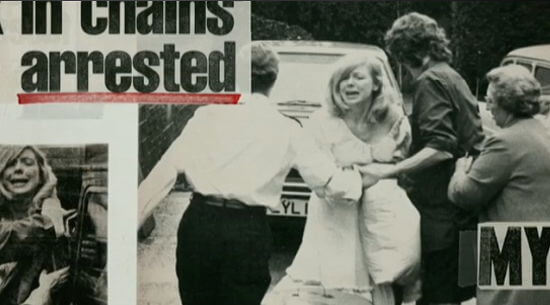

Tabloid journalism in Britain’s Daily Express and Daily Mirror brought international attention to Joyce McKinney in the 1970s, scandalizing her story with headlines like the “Case of the Manacled Mormon” that sold papers with a hyperbolic concoction of religion, sex, and crime. Errol Morris, heard but never seen in his 2010 documentary Tabloid, interviews McKinney and figures like Peter Tory, the late journalist who covered McKinney’s case. Though, the film does not delve into the history or sensationalizing practices of the tabloid press, even though it offers some remarks about the media’s general desire to know everything, the more perverse and outrageous the better. Its subject is primarily McKinney, whom Tory describes as “a bit crazy, eccentric, self-obsessed, and self-involved, and manipulative” but “not evil.” Maybe Tory’s assessment is correct, but Morris refuses to judge, and that leaves his film—in all of its wonderful, messy, salacious details—a singularly entertaining yet perceptive documentary.

Morris made Tabloid following two deathly serious probes into the U.S. military, The Fog of War (2003) and Standard Operating Procedure (2008). His examination of McKinney may, on the surface, seem to have nothing in common with those earlier films. However, like many of Morris’ documentaries, the topic of the film seems secondary to the way his interview subjects form their own truth out of their experiences. He allows his subjects to chatter on, and through their statements, the audience derives some manner of truth from their accounts. Perhaps they make a confession and slip some detail that amounts to an admission of guilt, as they do in his masterpiece, The Thin Blue Line (1988). Or perhaps they reveal their bizarre, albeit unique and fascinating outlook of the universe, as Stephen Hawking does in A Brief History of Time (1991). In any case, his films do not settle on a particular version of the truth; rather, they find an elusive strain of truth drifting in the space between certainties.

Tabloid stories are not uncommon in Morris’ oeuvre. He started out in the 1960s wanting to make a film about Ed Gein, the notorious serial killer, cannibal, and maker of flesh-lamps that provided the basis for cinema psychos like Norman Bates and Leatherface. Morris interviewed Gein and his doctors at a hospital for the criminally insane in Wisconsin, hoping to turn his interviews into a film that never materialized. Later, he turned to a tabloid-esque story in the San Francisco Chronicle about more than 500 pet graves that were being transported from Los Altos, California to Napa Valley. Upon his investigation in his 1978 debut Gates of Heaven, he uncovered the eccentric world of pet owners who place so much value in their pets or, in other cases, the pet cemeteries that see an opportunity to exploit such people. Morris seems to celebrate their strangeness and delight in exposing the viewer to uncommon people of a rare breed.

Tabloid stories are not uncommon in Morris’ oeuvre. He started out in the 1960s wanting to make a film about Ed Gein, the notorious serial killer, cannibal, and maker of flesh-lamps that provided the basis for cinema psychos like Norman Bates and Leatherface. Morris interviewed Gein and his doctors at a hospital for the criminally insane in Wisconsin, hoping to turn his interviews into a film that never materialized. Later, he turned to a tabloid-esque story in the San Francisco Chronicle about more than 500 pet graves that were being transported from Los Altos, California to Napa Valley. Upon his investigation in his 1978 debut Gates of Heaven, he uncovered the eccentric world of pet owners who place so much value in their pets or, in other cases, the pet cemeteries that see an opportunity to exploit such people. Morris seems to celebrate their strangeness and delight in exposing the viewer to uncommon people of a rare breed.

Joyce McKinney is about as uncommon as they come. With a genius-level IQ and a penchant for collecting the very men who obsess over her, the former beauty queen recalls her infamous case in interview format. Morris interrupts her accounts with blackout frames, jump-cuts that resituate her in the frame, and chapter titles designed to look like newspaper headlines. Despite the formal toying and playfulness by its director, the film’s most lively segments involve McKinney herself. She paraphrases Brigitte Bardot at one point, saying, “I gave my youth to men, and my old age I give to dogs that I trust.” In her youth, McKinney was a sparkling and virginal beauty whose gaze was captured by Kirk Anderson, a dopey guy who nonetheless became her obscure object of desire. McKinney suggests they were deeply in love, except Anderson’s Mormon family frowned upon any such union. When Anderson disappeared to England to complete a young Mormon’s required missionary duties, McKinney believed he was kidnapped by a cult and resolved to free him.

Having secured the company of two other men (a pilot and bodyguard), McKinney headed to London, located and freed Anderson, and then took him to a hideaway where she attempted to deprogram him through three nights of sex, bondage, and home-cooked meals. Apparently successful, McKinney returned to London with her beau with plans to marry; instead, she was arrested for kidnapping. Her tawdry tale ended up becoming tabloid fodder in the Daily Express, and she earned some small degree of popularity in the celebrity scene while on bail. Soon enough, she amazingly evaded authorities to get back to the U.S., using a forged passport and posing as a deaf-mute, but she was pursued by reporters. After some considerable digging, the Daily Mirror uncovered an unexpected twist: McKinney has long served, in some capacity anyway, as a sex worker and dominatrix to support her lifestyle and “rescue” trip to England—a notion supported by dozens of illicit photographs and sexualized personal ads.

Having secured the company of two other men (a pilot and bodyguard), McKinney headed to London, located and freed Anderson, and then took him to a hideaway where she attempted to deprogram him through three nights of sex, bondage, and home-cooked meals. Apparently successful, McKinney returned to London with her beau with plans to marry; instead, she was arrested for kidnapping. Her tawdry tale ended up becoming tabloid fodder in the Daily Express, and she earned some small degree of popularity in the celebrity scene while on bail. Soon enough, she amazingly evaded authorities to get back to the U.S., using a forged passport and posing as a deaf-mute, but she was pursued by reporters. After some considerable digging, the Daily Mirror uncovered an unexpected twist: McKinney has long served, in some capacity anyway, as a sex worker and dominatrix to support her lifestyle and “rescue” trip to England—a notion supported by dozens of illicit photographs and sexualized personal ads.

And while the “Case of the Manacled Mormon” itself presents a spicy tale of deception, criminal acts, and various forms of debauchery, McKinney’s compelling, often hilarious, and rather convincing account creates a delightful contradiction. (On allegedly raping Anderson, she says such an idea is absurd, like “putting a marshmallow in a parking meter.”) As a rule, Morris refuses to ask confrontational questions, as they incite a defensive reaction that seems less likely to arrive at the personal truth of his interviewee. In allowing McKinney to tell her version of the story, the resulting reasons behind the so-called kidnapping seem like a heroic act of love and romance. The story becomes increasingly complex as it goes, incorporating the tabloid findings and pictures of McKinney’s sordid life, all of which she denies. But as evidence conveniently disappears and McKinney insists on a conspiracy of cheap journalistic tactics, the questions remain and the truth lingers somewhere in-between.

Stranger still is how, after three decades out of the limelight following a supposed nervous breakdown, McKinney returns, under another name of course, in yet another bonkers story: A South Korean cloning scientist has replicated her beloved pit bull terrier, Booger, who has died of old age, into five Booger-clones (Booger McKinney, Booger Lee, Booger Ra, Booger Hong and Booger Park). Given her amazing life, always unexpected behavior, colorful wit, and evident charm, it’s not difficult to imagine McKinney drawing men and devoting them to her cause, as she often does through the course of her account. Morris’ own fascination with McKinney saturates the film, and in some small way, McKinney may have captured Morris too. Certainly, Tabloid seems at once enamored and regretfully skeptical of McKinney’s story, albeit with an unjudgmental admiration for her version of the events.

Each interviewee offers their representation of the world, and each of the worlds represented in the film have points where they intersect. Perhaps that intersection marks a place of factual significance or perhaps it’s just a coincidence. There’s no way to know, in most cases. Much like Werner Herzog, who considers his documentaries to be “films” and not necessarily works of nonfiction, Morris believes that nonfiction is an illusion, and truth, like a historical account or a documentary, may not be fully informed. As a result, he considers his films to be less documentaries than a unique form that, depending on the film in question, may change with each new film. If audiences are meant to discover an entirely new form of filmmaking whenever they sit down to one of Morris’ features, it explains why his works remain so engaging.

Each interviewee offers their representation of the world, and each of the worlds represented in the film have points where they intersect. Perhaps that intersection marks a place of factual significance or perhaps it’s just a coincidence. There’s no way to know, in most cases. Much like Werner Herzog, who considers his documentaries to be “films” and not necessarily works of nonfiction, Morris believes that nonfiction is an illusion, and truth, like a historical account or a documentary, may not be fully informed. As a result, he considers his films to be less documentaries than a unique form that, depending on the film in question, may change with each new film. If audiences are meant to discover an entirely new form of filmmaking whenever they sit down to one of Morris’ features, it explains why his works remain so engaging.

Tabloid will not free anyone wrongly imprisoned like The Thin Blue Line, nor does it reflect on a sweeping military history as The Fog of War, nor even an ugly scandal that Standard Operating Procedure ripped from contemporary headlines. In the place of such ultra-serious material, Morris provides an incredibly entertaining and surprisingly emotional study of his subject. In an interview with Film Comment, Morris remarked that his films seek to capture “the complexity of reality”—a notion that, by its nature, should be impossible to portray onscreen. Indeed, the director has since admitted that he does not understand McKinney. How could anyone, given the disarray of conflicting accounts and inconsistent facts in her case? Of course, we must also remember her incredible intelligence and ability to shape her reality. Could she be a delusional madwoman? Is she a criminal genius? To borrow a line from the film, the truth seems to be somewhere in-between—a persistent message in Tabloid and all of Morris’ work. So while the film contains elements that prove sleazy, at times incredibly funny, but also carry an unquestionable sadness, Morris’ camera remains trained on his interview subjects, and he does not judge.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review