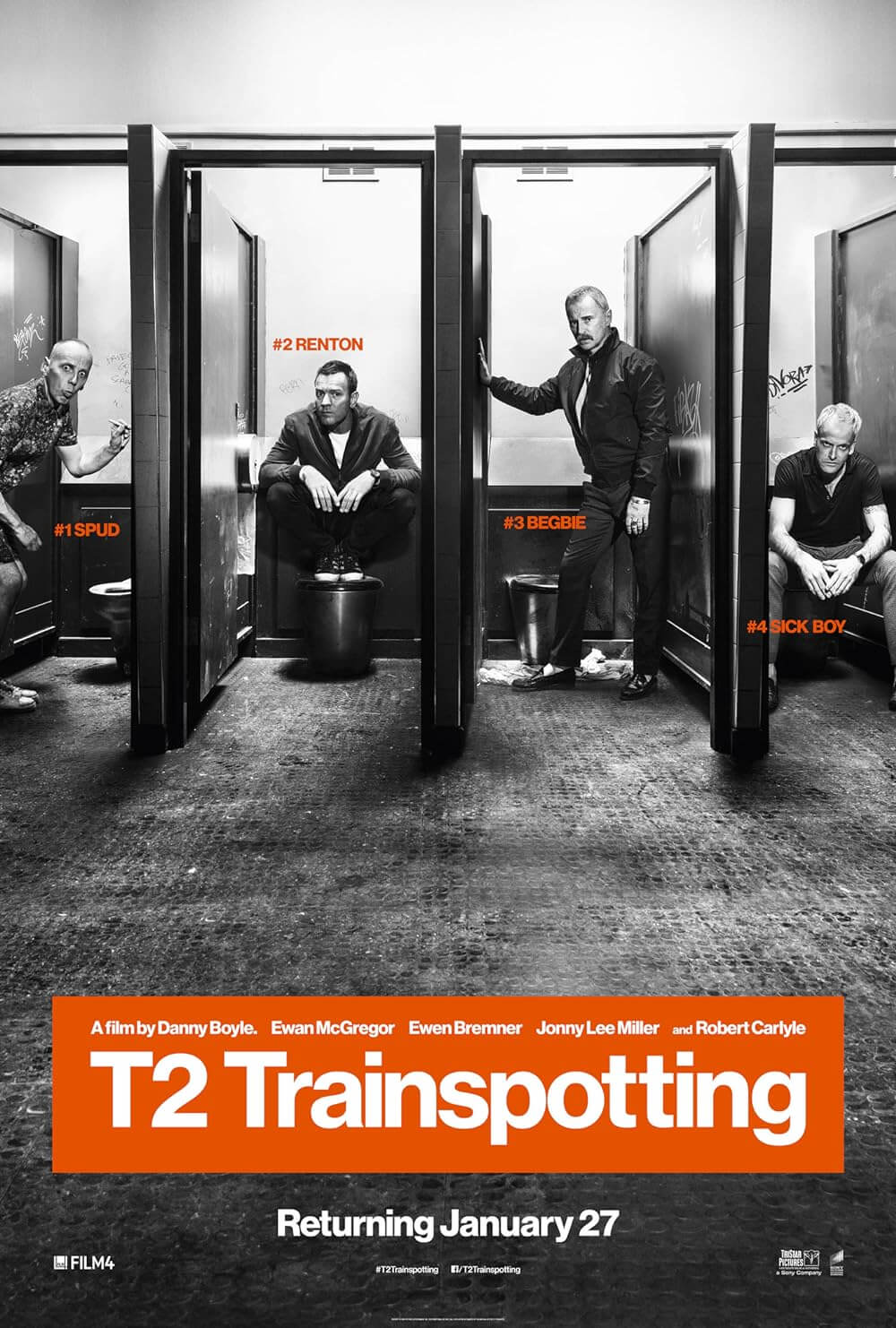

T2 Trainspotting

By Brian Eggert |

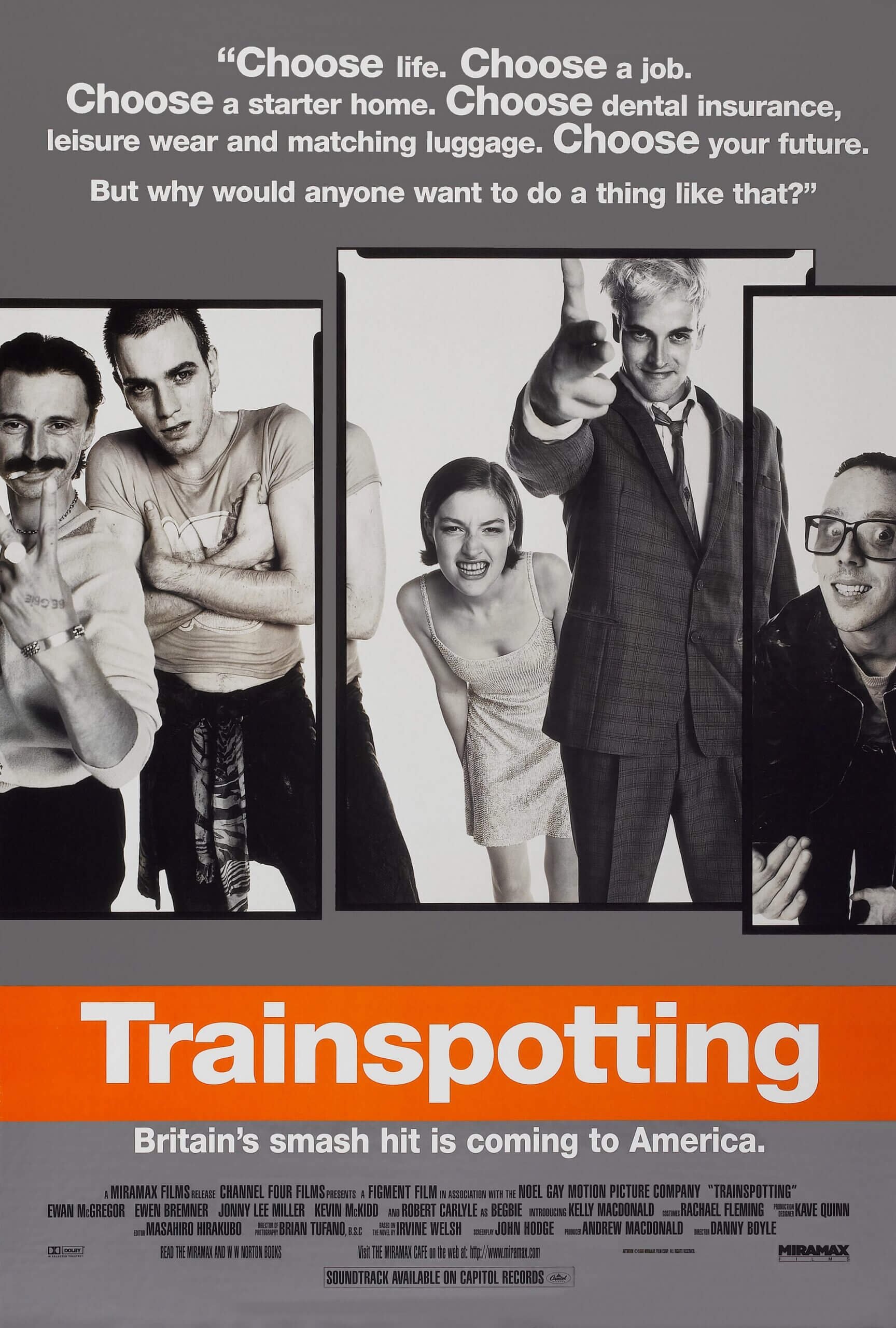

Over twenty years ago, the infectious drums of Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life” opened Trainspotting against the sprinting shoes of Mark Renton, played by a baby-faced Ewan McGregor, as he evaded pursuers on the streets of Edinburgh. The crackle of Danny Boyle’s direction and the caustic edge of Irvine Welsh’s base novel formed into a work that shaped the zeitgeist of the 1990s, and surely marked a high point in all of Scottish cinema. But T2 Trainspotting is something altogether different. The sequel opens in a gym with a low angle shot of sneakers on a treadmill, the pulsating beat of High Contrast’s “Shotgun Mouthwash” on the soundtrack. Boyle’s camera dizzily moves around the room, capturing the sweaty expressions of young joggers, until the frame returns to the feet from the first image, and then up to the face of a middle-aged, tired looking Mark Renton, who then collapses from a mild heart attack.

Boyle’s sequel reconnects with its characters two decades later and treats them with a refreshing dose of the humanity and self-reflectivity that come with age. No longer can Renton, Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), Spud (Ewen Bremner), and Begbie (Robert Carlyle) dash around Edinburgh, recklessly shooting skag (heroin) and satiating every impulse. Age has caught up with them. Though any skepticism toward a long-belated sequel to Trainspotting proves warranted, fortunately, it also proves unnecessary. T2 considers what happens after the heyday of drug-fueled antics subside and boys become adults. The film treats its characters like human beings rather than pop-culture icons of a commercially viable sequel. Aside from the silly title, the film provides everything fans could have hoped for from a sequel, and maybe more, given its mature and surprisingly resonant treatment.

Perhaps surprise is unfair. After all, Boyle’s famed technical inventiveness and the visual touches of his longtime cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle—variations in lenses, cockeyed angles, several camera types, neon lights, and surreal video projections—seldom overshadow his mastery for bringing characters to life. (Take Sunshine, 127 Hours, and Trance as proof.) Moreover, the sequel draws from Welsh’s follow-up book, titled Porno, which took place ten years after the events in Trainspotting. With another ten years added, a prevailing irony lingers throughout T2 over how its characters famously preach “choose life” and yet, being a sequel set so long after the revered original, the film itself risks being a nostalgic trifle. However, screenwriter John Hodge had incorporated the theme of nostalgia into the sequel, so its characters look into the past for memories more cherished than their current, underwhelming lives. Regardless of dead babies and lost friends, or having emerged from “the worst toilet in Scotland,” they think of their youth as the halcyon days, as middle-aged men often do.

Another irony finds Renton unhappily married in Amsterdam after stealing £16,000 from his three cohorts at the end of the original (given Renton’s pronounced love of footballer Archie Gemmill’s goal against Holland in the 1978 World Cup, it seems odd that he would choose Amsterdam of all places to escape). But then, things haven’t worked out well for him there (heart attack among them), and when he returns to Edinburgh to feel at home again, he attempts to make amends with those he’s wronged. He finds Spud, now divorced from his wife (Shirley Henderson) and estranged from his son, living as a suicidal skag junkie looking for a reason to live. Sick Boy goes as Simon now and runs a pub, with a little blackmailing escort service on the side. He snorts cocaine regularly and dreams of opening a brothel along with his girlfriend Veronika (Anjela Nedyalkova). Begbie, meanwhile, has been rotting away in prison and blames Renton for his lost time.

Another irony finds Renton unhappily married in Amsterdam after stealing £16,000 from his three cohorts at the end of the original (given Renton’s pronounced love of footballer Archie Gemmill’s goal against Holland in the 1978 World Cup, it seems odd that he would choose Amsterdam of all places to escape). But then, things haven’t worked out well for him there (heart attack among them), and when he returns to Edinburgh to feel at home again, he attempts to make amends with those he’s wronged. He finds Spud, now divorced from his wife (Shirley Henderson) and estranged from his son, living as a suicidal skag junkie looking for a reason to live. Sick Boy goes as Simon now and runs a pub, with a little blackmailing escort service on the side. He snorts cocaine regularly and dreams of opening a brothel along with his girlfriend Veronika (Anjela Nedyalkova). Begbie, meanwhile, has been rotting away in prison and blames Renton for his lost time.

For the actors, among them a brief appearance by Kelly Macdonald, there’s no awkwardness slipping back into the roles that launched their careers. In many ways, their characters have grown up and become wiser; but, like many men in their forties, they remain boyish and floundering through adulthood. Consider T2 their mid-life-crisis-of-a-film, where Renton finds himself rekindling his past, restoring the jocular man-crushes between friends, and inciting a new strain of bad behavior. To compensate for his previous betrayal, he tries to help Simon launch his brothel by committing all manner of heinous, money-raising crimes. In the meantime, Spud finds he has a knack for writing about his former exploits, in his own indiscernible way, while Begbie escapes from prison, vows revenge on Renton, but finds his aged body doesn’t have the same vitality it used to. Indeed, the harsh realities of age and the equal measures of value and pointlessness of hanging onto the past emerge throughout the film.

Of course, T2 inherently lacks the originality and novelty of its predecessor, but the sequel deepens its characters in unexpected ways. Boyle incorporates flashbacks that acknowledge how formative the boyhood relationships among these men were, showing something akin to Super 8 footage of their youth, or scenes from the original film restylized to avoid a typical flashback structure. The ease with which their friendships return to their old patterns feels realistic and, like any boy’s weekend between grown men, its charm inevitably comes to an end. The film acknowledges that nostalgia remains an active force in the sometimes sad and debauched lives of the middle-aged, as evidenced by the reemergence of 1980s-90s franchises in today’s pop-culture. But rather than deal with this phenomenon by satiating the audience’s predictable desire to savor the original, Boyle’s film allows its characters their moments of nostalgic escape, yet ultimately returns them to the unromantic reality of middle-age (captured with horrifying humor by the film’s use of The Rubberbandits’ video for “Dad’s Best Friend”).

Even so, Boyle has constructed another film that feels as though pure energy has been channeled onscreen. Several memorable sequences throughout T2 seize the same manic impetuousness of the original, reflecting the characters’ desire to relive their youth. Watch the sequence when Renton and Simon find themselves onstage before a crowd of rather awful 1690ers, singing an impromptu song to celebrate Protestant William of Orange’s victory over Catholicism at the Battle of the Boyne (little does the crowd know, their wallets have just been stripped by the performers). Later, there’s a lively duo of chase sequences where the enraged and bloodthirsty Begbie hunts Renton by foot on Edinburgh’s cobblestone streets. Though such moments evoke the original, the smaller, human scenes define the sequel: The warm treatment of Spud; Begbie’s affecting realization that he has become just as misguided as his wino father; and Renton’s return home to find his father (James Cosmo), still living a noble and quiet life.

Even so, Boyle has constructed another film that feels as though pure energy has been channeled onscreen. Several memorable sequences throughout T2 seize the same manic impetuousness of the original, reflecting the characters’ desire to relive their youth. Watch the sequence when Renton and Simon find themselves onstage before a crowd of rather awful 1690ers, singing an impromptu song to celebrate Protestant William of Orange’s victory over Catholicism at the Battle of the Boyne (little does the crowd know, their wallets have just been stripped by the performers). Later, there’s a lively duo of chase sequences where the enraged and bloodthirsty Begbie hunts Renton by foot on Edinburgh’s cobblestone streets. Though such moments evoke the original, the smaller, human scenes define the sequel: The warm treatment of Spud; Begbie’s affecting realization that he has become just as misguided as his wino father; and Renton’s return home to find his father (James Cosmo), still living a noble and quiet life.

Boyle and the cast have made an essential sequel filled with humor, energy, and beloved characters, but it’s never just a lightweight journey into nostalgia. Adulthood remains a superficial label in T2, something that comes not with age but through a conscious decision for maturity. Indeed, the original followed twentysomethings into arrested development; the characters denied the reality of their lives in favor of escape through drugs and crime, in essence trying to jealously preserve their youth. In the years since, each of them has made a lousy attempt to become a man, and only through the events in the sequel do they accomplish this. As a result, the motto “choose life,” once again used here in a striking speech that critiques our so-called advanced society, is more relevant than ever, beckoning its characters to move beyond the hang-ups of their youth and instead move forward in their lives. Although the film’s self-reflexive quality is to be expected, the enriching themes make it arguably more moving than its predecessor, and certainly among the best of any sequels.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review