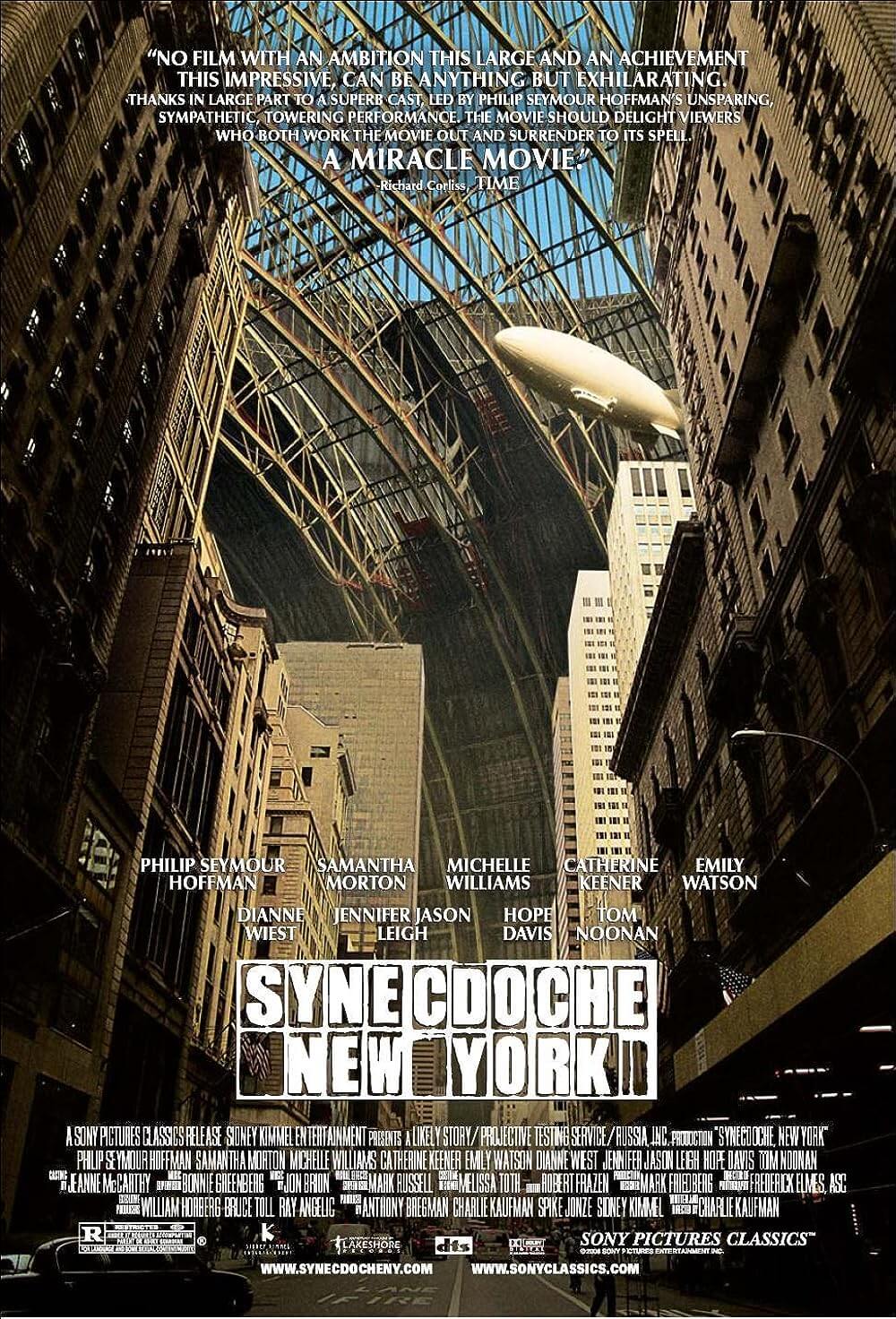

Synecdoche, New York

By Brian Eggert |

Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York wanders the epic, heartbreaking arena of the mind. This is where regret, longing, and doubt eat away at the creative process while simultaneously feeding it, a frequent topic in Kaufman’s films. On a grander scale, the film’s theme is existence itself, which art often attempts to represent. Somewhere along the way with particularly inward artists, their work stops imitating life, and the two become confused. Life and art wrap around each other until the lines delineating representation and reality blur. Having written such escapades of the psyche as Being John Malkovich, Human Nature, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Kaufman’s prevalent theme has been about losing oneself in the landscape of the mind. In each case, the protagonist struggles to separate, or even realign, their psychological Self with the physical world around them, finding the two realities naturally at odds with each other. With Synecdoche, New York, Kaufman’s directorial debut, those themes handled in the past by Spike Jonze and Michel Gondry are now fully realized with all the craftsmanship of a longtime auteur, straight from the source of their brilliance.

Before describing the film’s content, let me first explain that title you’re wondering about, because chances are, aside from those who’ve studied metonymy or poetry, the word “synecdoche” seems strange and foreign. Admittedly, the word itself is awkward, like the pronunciation of a sneeze. And it doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue. The term denotes an expression wherein a part stands in for the whole, such as “I need a new pair of wheels,” and here the “wheels” imply an entire automobile. On a basic level, Kaufman refers to a smaller piece of New York City that signifies the actual whole of New York. But then there’s the metaphoric explanation, which you can determine after your own viewing.

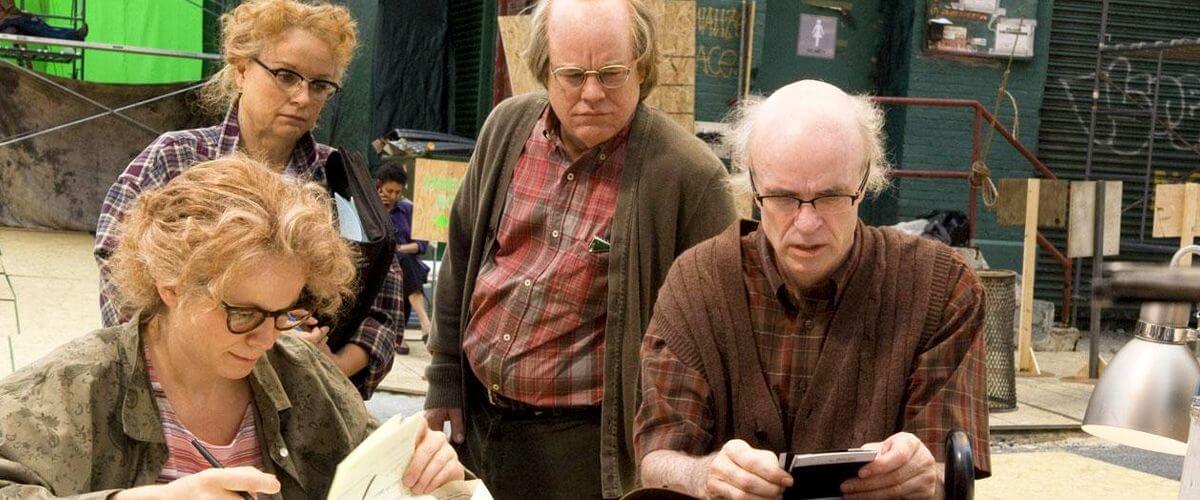

The story involves theater director Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who lives with his celebrated miniaturist painter wife, Adele Lack (Catherine Keener), and their 4-year-old daughter, Olive (Sadie Goldstein), in suburbia. Judging his life’s success by that of his work, Caden loses sight of both, and thus both spiral out of control. Adele leaves for Berlin with Olive on “vacation” for a month, and after a short period for Caden, he’s told she’s been gone for a year. Has he lost track of that much time? Is he mentally ill? Is he going to die as he always claims? Something is undoubtedly wrong with him. He erupts into seizures without warning. An ophthalmologist tells him to see a neurologist when his pupils stop working. Pustules sporadically appear on his face and legs, which he admits is sycosis, an inflammatory skin condition, and not psychosis. But we begin to wonder. His salesperson-of-a-shrink (Hope Davis) is not there to help him as much to sell her prolific collection of self-help guidebooks. The happiness yarn she’s spinning, however, is false and impossible for Caden. Even when the flirtatious box-office clerk Hazel (Samantha Morton) makes a direct sexual pass at him, he can only cry apologetically, unable to complete the deed, saying he’s dying and lonely and confused.

Issued a prestigious MacArthur “genius” grant, Caden is given seemingly unlimited resources to explore a new stage project. His idea is to “capture life” and put himself into something. However frequently artists say things like this, Caden takes it further, renting a massive warehouse in Manhattan where inside he assembles a smaller version of the world outside. Using full-scale replicas and thousands of extras, each with assigned roles, he spends years employing actors to portray people from his life, recreating every detail. His second wife, Claire (Michelle Williams), plays herself, while Caden is played by Sammy (Tom Noonan), Caden’s stalker who confesses, “I’ve been following you for 20 years, so cast me and see who you really are.” Lost in his planning, a stagehand eventually asks Caden, “When are we going to get an audience in here? It’s been seventeen years.”

Caden’s face grows older. His obsession with the project moves from capturing life to relying on his fantasy to live for him. Caden and his assistant Hazel follow behind the actors playing Caden and his assistant Hazel, one making notes on the other one’s observations. But then, there’s a third Caden and Hazel, the actors portraying the actors. Rapt by a creative drive and driven mad by its passion, it’s no wonder he assigns the ever-rehearsing play titles like “Infectious Diseases in Cattle.” Through it all, he hopes for something great and astonishing to come by and sweep him out of his lifelong funk—an artistic or emotional epiphany, perhaps. Waiting for that, life catches up with him; art imitates life and eventually precedes it, passes him by entirely.

Hoffman’s performance contains a delicate and saddening foundation, fully committed to by one of today’s finest actors. Kaufman’s protagonists are habitually unsympathetic, self-involved types, and their fates seem detached from the audience’s compassion. Caden Cotard, by way of Hoffman, holds our hearts with his tragically fragile grasp. Hoffman has played brash (Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead), melancholy (The Savages), and channeled the depths of inner woe (Capote), but he’s never transcended his own talent with a tour-de-force such as this.

Earning itself a comparison to the great films of the mind, Kaufman’s masterpiece tests the audience’s sense of stability, forcing us to question every scene, its origins, and then, as more is revealed, go back and reconsider them. Seeing it once is not enough. Like Fellini’s 8 ½ and Gilliam’s Brazil, the picture exists on a plane of uncertainty that asks us to consider its meaning, examine the details, and speculate. What we’re shown is unreliable and symbolic. Of course, trying to see the picture on any kind of linear surface is impossible. We must circulate around the thing, ponder, and deliberate. Ironically, orbital thinking is exactly what gets Caden into his predicament, but no matter. Perhaps a more appropriate metaphor is that we should dive into the material and allow its waters to surround us.

We draw from such introspective viewing an appreciation for the text, both in its ability to present a puzzle box we cannot resist attempting to open and in its abundant rewards upon our discovery of its secrets. Synecdoche, New York aches with sentiments on a life (and indeed all life) not fully lived and overly focused on analysis and reflection, offering rich commentary on remorse and alienation, how inaction and self-pity ultimately prevent forward motion and negligence of time, and do nothing to prolong inevitable death. Such profound observations are rarely paired with ambitious filmmaking this rich.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review