Synchronicity

By Brian Eggert |

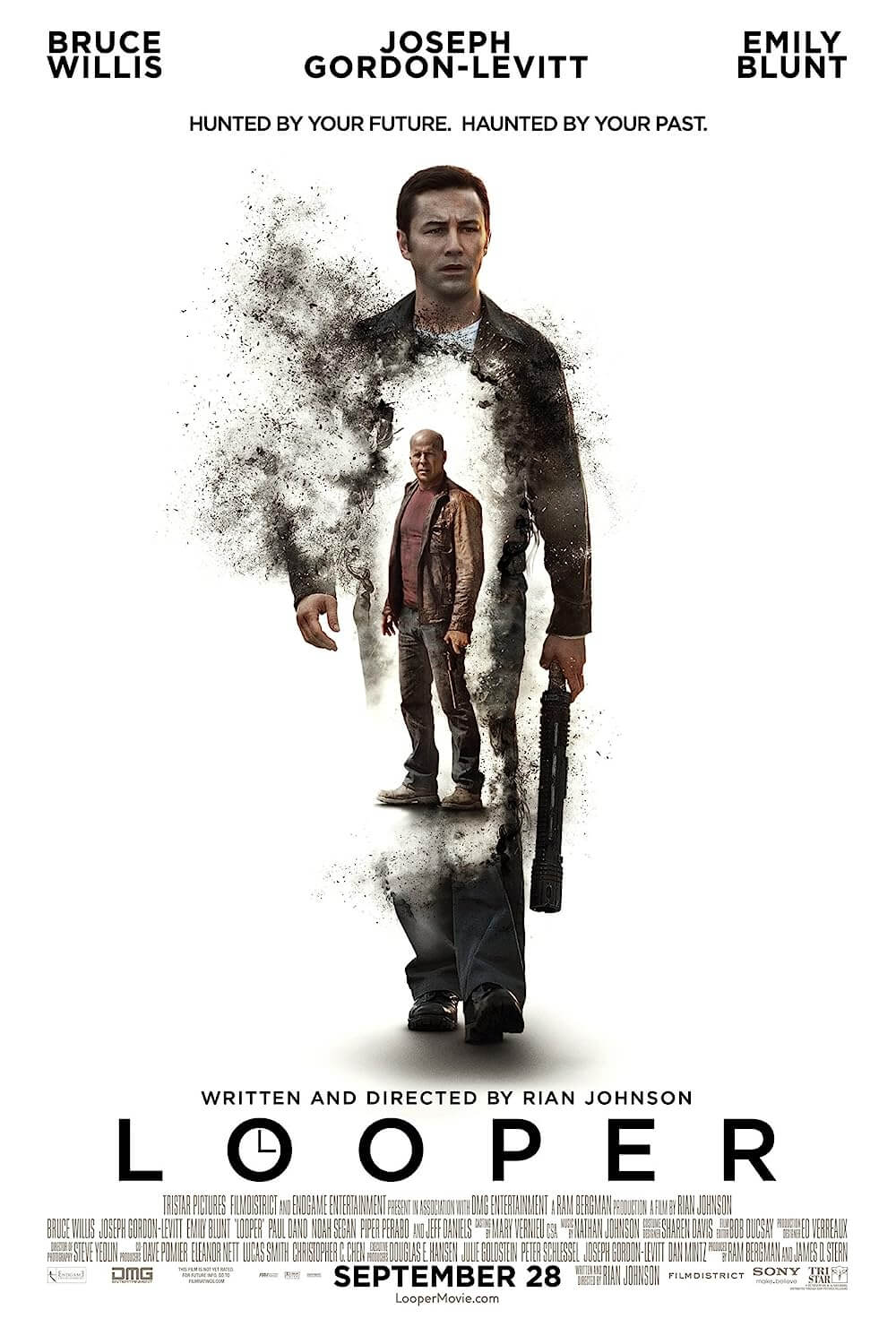

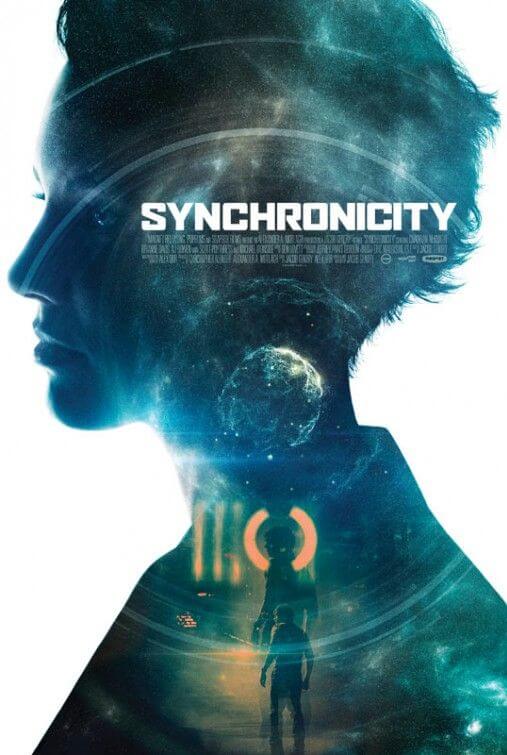

Whenever you open a “traversable wormhole in the space-time continuum,” you’re bound for trouble. If you take anything away from Synchronicity, let it be that lesson. A time-travel mindbender from the mind of writer-director Jacob Gentry, one of three director-contributors to the horrifyingly good cinematic exquisite corpse The Signal, the film has much in common with similar low-budget fare like last year’s Predestination or the memorable Primer from 2004, as opposed to larger studio efforts like Edge of Tomorrow (2014) or Looper (2012). Filled with visual and aural cues to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, this fascinating production relies far too much on an uninvolving love story instead of its more interesting, and head-scratching, forays into brainy and theoretical science.

At first glance, Gentry’s production is almost distractingly fond of Blade Runner and its futurist noir elements. Ben Lovett’s synth score evokes Vangelis with its dreamy notes and tones. Jeffrey Pratt Gordon’s production design looks gray and concrete, as if the entire film was shot in a series of parking garages meant to look like apartment buildings and laboratories. Cinematographer Eric Maddison shoots light shining through blinds in dusty spaces, and he uses lens flares to capture the random spotlights that pervade Synchronicity‘s setting, a futuristic metropolis with skylines rendered via cheap CGI. Despite Gentry’s lofty aspirations and homages, the budget gives away the artifice. Presumably because of financial limitations, the film cannot saturate the viewer in the time and place as Scott’s film did. There are no signs of the political or social consequences of this future. It’s just a big, anonymously claustrophic cityscape.

Somewhere in that city, tucked away in a small lab, physicist Jim Beale (Chad McKnight) and his brainy assistants Chuck (AJ Bowen) and Matty (Scott Poythress) finish tests on a time-travel device that will open one end of a wormhole. While his project has remained free of outside money or resources until now, Beale needs capital to complete a final test. Enter venture-capitalist Klaus Meisner (Michael Ironside), who insists on owning a piece of Beale’s machine if a successful test is to be completed with his money. As the film points out in an already obvious historical parallel, Beale is the Nikola Tesla to Meisner’s Thomas Edison—a true genius subject to the bullying and financial influence of his competitor. But rather than use a simple corporate takeover, Meisner uses the resident femme fatale and love interest, Abby (Brianne Davis), whose motives change throughout the film as she engages Beale.

Of course, something unexpected occurs with Beale’s experiment, and the film enters a Back to the Future-esque scenario where various versions of Beale from different timelines are wondering about. We see scenes that we’ve seen before, only from a different Beale’s perspective, and everything seems to fold over on itself. All the while, Beale snaps in and out of trippy wormhole dreams, realized with lava lamp psychadelics. At the same time, the assorted Beales are falling in love with the assorted Abbys, although it’s anyone’s guess why. Their love is more of a weak subplot to the main temporal spaghetti of tangled timelines and inter-dimensional crossovers. Keeping everything straight may prove an understandable challenge for some, but Gentry doesn’t seem to care, focusing instead on the love story to guide his audience through the plot’s tangled web. Devoid of charisma or natural charm, McKnight and Davis never really connect with each other or the audience. If only Gentry had spent more time on expanding Beale and Abby’s connection.

This critic could write an entire review discussing all the ways in which Gentry borrows from other material from Robert Heinlein to Philip K. Dick to compile his film, but what it comes down to is whether the story was engaging. For example, Looper did a much better job of putting the emotional drives of the characters ahead of the cold temporal science. Unfortunately, the science-fiction elements of Synchronicity take a back seat to a humdrum love story, which remains underdeveloped and quite unbelievable. Because of the twisting machinations of the plot, Jim and Abby, and their ever-changing motives depending on the timeline they’re in, never feel consistent enough to draw our empathy. The film is at its best when it’s considering the endless possibilities (and catastrophes) of what Jim and his team have created. Although an intriguing piece of science-fiction and an impressive production that will keep your attention from start to finish, it ultimately leaves the viewer fond of, but cold toward, the experience.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review