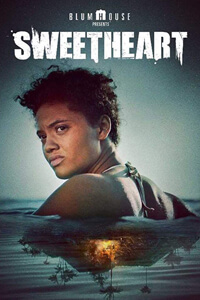

Sweetheart

By Brian Eggert |

In the canon of movies about one or two characters marooned on a desert island, only a few stand out. They feature performers capable of holding the viewer’s attention without the need for a sprawling cast. Such movies require actors with charisma to spare, with the capacity to intimate using their body language to create a whole personality and backstory, even though the screenplay may not provide it. Among the few, Tom Hanks in Cast Away (2000), Toshiro Mifune and Lee Marvin in Hell in the Pacific (1968), and Paul Dano and Daniel Radcliffe’s farting corpse in Swiss Army Man (2016) serve as compelling examples, whereas the opposite is true of Madonna in her 2002 vanity project Swept Away. Director JD Dillard’s Sweetheart finds Kiersey Clemons washed up on an island, where she’s forced to hunt for food and scrap for supplies to keep herself alive. At first, it seems to be an exercise in minimalism, until the screenplay by Dillard, Alex Hyner, and Alex Theurer devolves from an austere survivalist tale into a battle for dear life against a merman—the best way to describe what appears to be a cross between the monster in Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and, well, Merman from Masters of the Universe.

Clemons does what she can with her limited character, Jenn, who finds herself stranded on a small tropical island after a boat accident. Though she can walk around the island in a few short hours, the usual problems of food and water resolve themselves without effort: the interior jungle contains cocoanuts aplenty, while every morning fish conveniently wash ashore. She also finds evidence that others had been trapped on the island and failed to escape. Grave markers and leftover supplies, including a Game Boy, suggest a few decades have passed since any other people set foot on these beaches. Watching Clemons craft spears, arrange a shelter, and navigate the shallows to snare larger fish by luring them with homemade chum has a fascinating quality to it, but Clemons an unsubtle acting style, making every action an overexpressed gesture. Still, she doesn’t hint at the person beneath the surface. And while the location shooting in Fiji makes for gorgeous scenery, the lack of backstory or exploration of the main character keeps the viewer at a remove.

Fortunately, things pick up when, each night, she hears some snarling creature in the dark. Dead fish and tree trunks bear violent slashes as evidence that something big and dangerous is out there. And soon enough, she sees a vague shape in the ocean. Later, while trying to recover a suitcase floating a hundred yards from the shore, she spies a dark hole at the bottom—the lair of an underwater merman, she suspects. I use the term “merman” because “monster” or “creature” gives the thing too much mystique. The merman’s design looks cheap in the CGI sequences when Jenn tries to escape its pursuit on the beach, leaping between the water and shore like a grasshopper. Alternatively, later sequences when Jenn fights the creature in a one-on-one battle reminiscent of Predator (1987), the guy-in-a-suit quality of the merman looks unintentionally funny. The thing is scariest in a single underwater scene, where it moves about elegantly and recalls the various amphibious men from Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water (2017) or Hellboy (2004).

Before long, another plot convenience finds Jenn’s boyfriend Lucas (Emory Cohen, from Brooklyn) and their friend Mia (Hanna Mangan-Lawrence. from TV’s Spartacus) approaching the island on a raft. Vague allusions to the trauma of their raft experience and the appearance of dried blood imply that perhaps the extra survivors weren’t always a twosome. They assume Jenn’s stories of a merman have resulted from the deserted island version of cabin fever, but when it inevitably shows up, the screenplay robs the viewer of the essential “I told you so” moment. The new characters offer a few more details about Jenn’s backstory, who she was before she started tangling with the apex predator of her new island home. Mia hints that Jenn was a pathological liar, and Lucas blames her for “always having a black cloud over her head,” derogatorily referring to her as “sweetheart”—the only clue to the title’s meaning.

The underwritten material submits itself as a self-actualization piece, where Jenn emerges from the demeaning realm of someone’s “sweetheart” to someone capable of hunting down a killer merman. And while that narrative trajectory sounds imperative as a B-movie premise loaded with potential, the filmmakers haven’t given Jenn an adequate platform to make her fulfillment of Self dramatically engaging. Dillard, who directed and co-wrote Sleight in 2016, about a street magician turned superhero, delivers another undercooked genre concept. The movie, which runs a mere 77 minutes without credits, barely allows itself time to invest in its protagonist. With its synth score by Charles Scott IV and capable cinematography by Ed Wu, Sweetheart nonetheless thinks its appeal resides in the human vs. monster setup. But that’s the movie’s least interesting aspect. The filmmakers overlook that a stranded-on-an-island concept sinks or swims on the strength of its main character, who never entirely comes to life in a compelling way here.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review