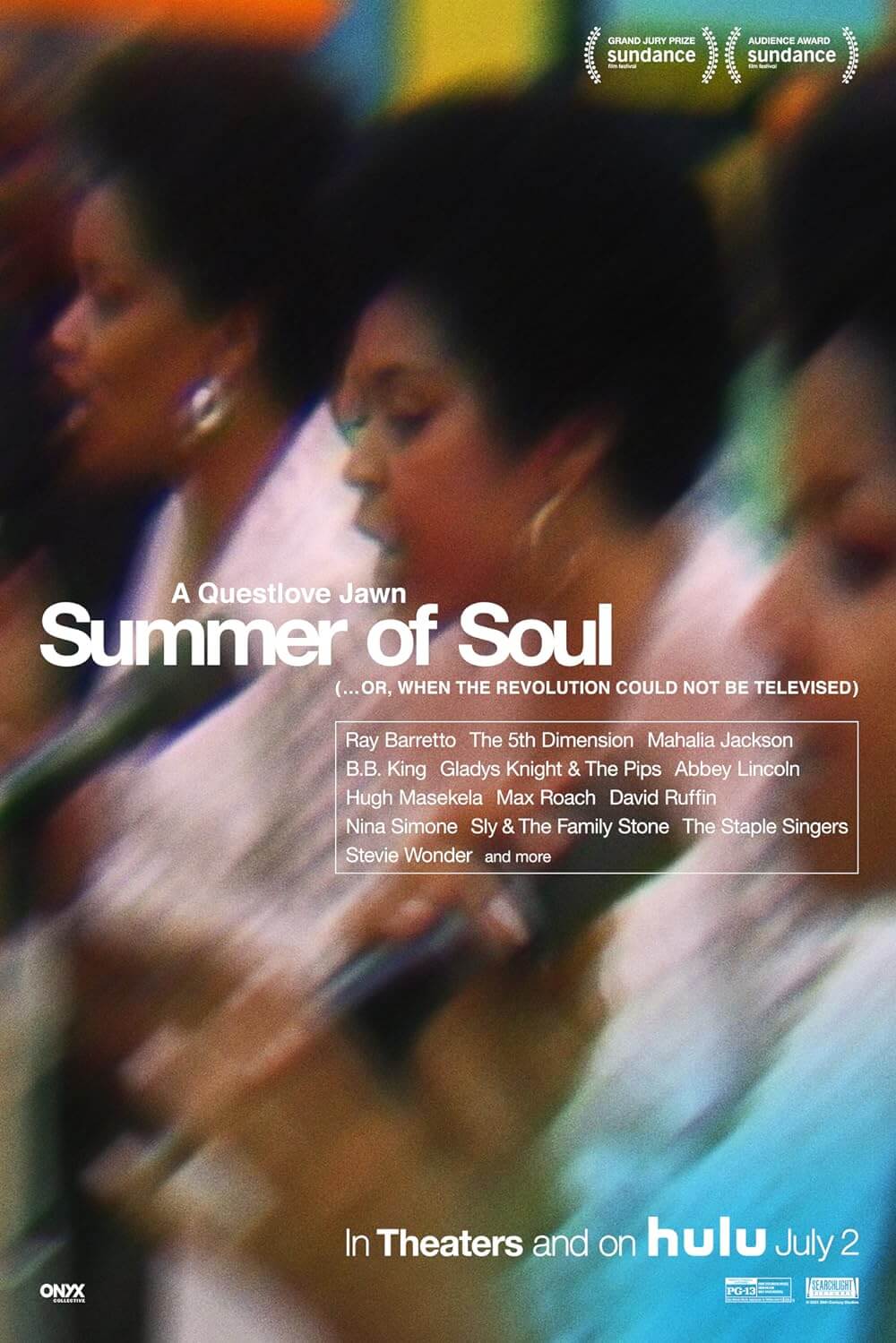

Summer of Soul (…or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)

By Brian Eggert |

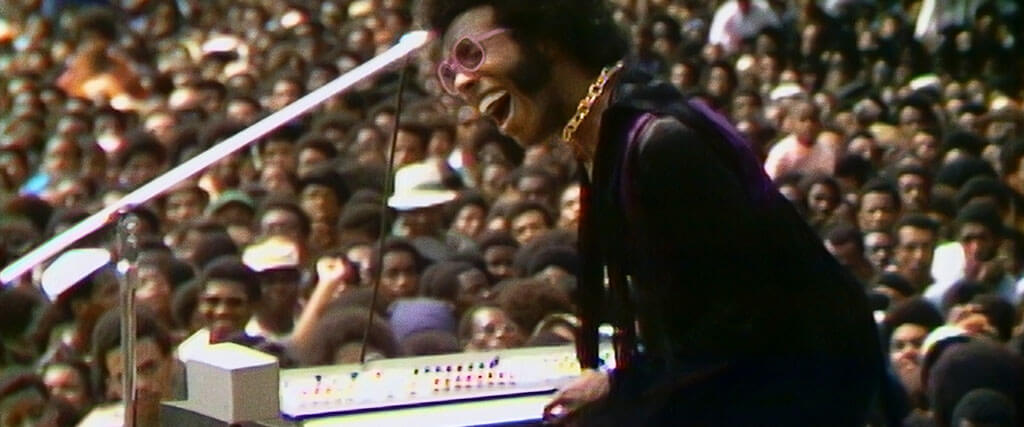

Summer of Soul (…or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) is a stirring account of American history. In the hottest months of 1969, the Harlem Cultural Festival hosted thousands of attendees over six weekends for a series of performances by Black musicians. During that time, the effect of the Stonewall riots reverberated through the country, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon, the Woodstock music festival took place a few hundred miles away, and the Manson Family killed Sharon Tate and several others. The year was among the most tumultuous on record, matched only by 2020. And the festival, sometimes called “Black Woodstock,” was overlooked in the media and all but forgotten by history. Most people who watch this documentary—directed by Ahmir Thompson, better known as Questlove—will probably not know about the festival before seeing or reading about the film. “Nobody would believe it happened,” says one interviewee. We will now.

The festival, directed and hosted by singer and so-called hustler extraordinaire Tony Lawrence, boasted headliners such as Sly and the Family Stone, B.B. King, The 5th Dimension, Stevie Wonder, and Nina Simone, to name just a few. The performers played a cross-section of musical genres ranging from Gospel to Blues, Jazz to Motown, R&B to Funk. Shooting in Mt. Morris Park with a limited budget, producer Hal Tulchin captured the festival on multiple cameras and 47 reels of footage, which has remained in storage for 50 years. Thompson learned of the footage and, in restoring and compiling a two-hour feature, presents a touchstone of not just musical history but Black history as well. Along with his editor, Joshua L. Pearson, he assembles a deliriously engaging celebration of the “ultimate barbeque,” as one festival attendee describes it. Another calls it something like a unification of “Black consciousness” vital in that time and place.

What Thompson does so well in Summer of Soul is twofold. First, he luxuriates in the performances. He allows the viewer to lose themselves in Stevie Wonder’s cover of the Isley Brothers’ “It’s Your Thing” and Nina Simone’s “Are You Ready?” He doesn’t turn the film into an endless series of talking-head interviews; he showcases the incredible footage, as he should, and creates a contagious feeling of being overwhelmed by what we’re seeing. Some 300,000 people of color assembled for six free concerts of primarily Black artists at a time when civil rights seemed to be at a tipping point for Black people in America. The previous years had seen the assassinations of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Kennedys; joblessness, poverty, and crime marked Harlem; Nixon was in the White House; and the trial of the Chicago 8 was around the corner. Indeed, the other superb aspect of Thompson’s film is his sense of historical context, framing the festival not only as an epic concert but a symbolic wholing of the Black community.

Summer of Soul seamlessly transitions between historical photos, news footage, archival interviews, Tulchin’s concert footage, and the occasional interview subject—among them Rev. Jesse Jackson and Lin-Manuel Miranda alongside his father, Luis. It feels kinetic, moving with efficient, crackerjack energy, and not one moment or image feels inessential. Thankfully, Thompson and his interviewees always work to frame the larger context, which deepens the onstage performances. There’s even some discussion of semiotics from Black intellectuals from the era, talking about the reclamation of identity through labels. Journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault details her battle to convince an editor for The New York Times to use “Black” instead of “negro,” leading to a point about the white culture setting up a dichotomy between white signifying good and black signifying bad. That might seem like dry material for a documentary, but it’s also intercut with the music that sings with pride and pain about a shared history.

Summer of Soul seamlessly transitions between historical photos, news footage, archival interviews, Tulchin’s concert footage, and the occasional interview subject—among them Rev. Jesse Jackson and Lin-Manuel Miranda alongside his father, Luis. It feels kinetic, moving with efficient, crackerjack energy, and not one moment or image feels inessential. Thankfully, Thompson and his interviewees always work to frame the larger context, which deepens the onstage performances. There’s even some discussion of semiotics from Black intellectuals from the era, talking about the reclamation of identity through labels. Journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault details her battle to convince an editor for The New York Times to use “Black” instead of “negro,” leading to a point about the white culture setting up a dichotomy between white signifying good and black signifying bad. That might seem like dry material for a documentary, but it’s also intercut with the music that sings with pride and pain about a shared history.

You might say the doc’s theme rest between storytelling and therapy. It tells the story of the festival, largely forgotten by time or actively denied its place in history due to lack of adequate funding; the story of America in 1969; of the attendees who could never forget their experiences; of the musicians, who had never seen so many Black faces gathered together before; and of how the musical genres fit into the larger mosaic of African-American art. Thompson remarks in the press notes about the significance of the footage finally hitting screens: “The fact that 40 hours of footage was kept from the public is living proof that revisionist history exists.” And so, the film recovers the music and these moments in time for today’s viewers, enacting a healing process. Referring to Gospel music, Rev. Al Sharpton talks about music as a way of clearing the soul: “We didn’t know anything about therapists. But we knew Mahalia Jackson.” Even so, it’s more than merely catharsis, says one interviewee: “There’s also rage and trauma.”

In some of the film’s best moments, Thompson centers on faces, and not just the faces of the festival’s iconic performers. One extraordinary scene features legend Mahalia Jackson singing “Take My Hand Precious Lord,” just moments after Rev. Jesse Jackson tells the crowd that MLK referenced the song in his final words. Just then, the film cuts to an attendee’s face. It’s a man watching with a smirk of disbelief as Ms. Jackson, joined by Mavis Staples, unleashes herself on the microphone in an unbelievably raw vocal and physical performance. The man is moved and yet wholly absorbed, and we can only imagine what he’s feeling in that instant. Thompson echoes this by showing footage of the festival to his interviewees, and we see the light from an offscreen monitor illuminating their amazed faces. These expressions convey a kind of second-hand recognition about the monumentality of this footage, which, especially in recent years, echoes through time.

Summer of Soul is more fluid and urgent than most documentaries, concert films or otherwise. It deftly blends history, culture, politics, and art with a rare harmony of breadth and depth. And one can only hope that Summer of Soul is just the tip of the iceberg. With any luck, the interest in this concert will lead to many more hours of this footage becoming available, perhaps in another film or longer series format. After all, Woodstock received a five-and-a-half-hour documentary account courtesy of director Michael Wadleigh in 1970. With nearly as many attendees and hours of footage left unseen by the public, the Harlem Cultural Festival deserves the same treatment. Thompson has introduced and implanted an urgent demand for more footage of the festival, as well as supplying an account of how Black history is inextricably tied to American community and identity.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review