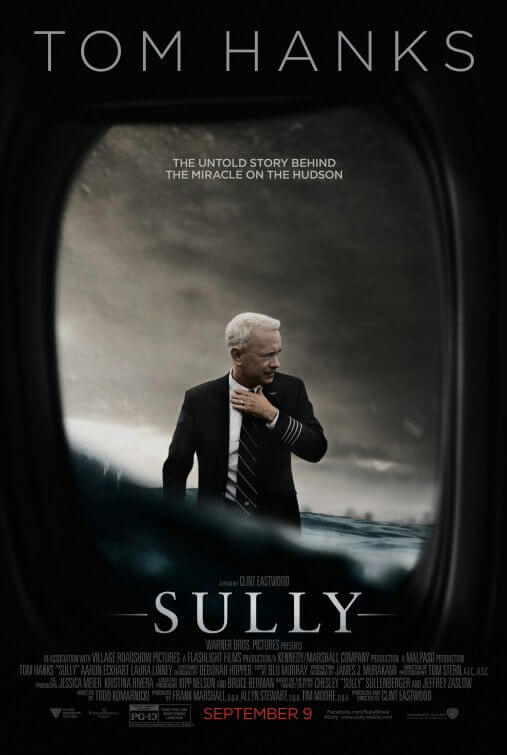

Sully

By Brian Eggert |

On January 15, 2009, US Airways Flight 1549, piloted by Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, struck a flock of geese just moments after leaving LaGuardia Airport, rendering both engines unresponsive. Relying on his forty years of commercial airline experience, Sully and his First Officer Jeffery Skiles tried heading back to LaGuardia, but without the proper altitude to make it, they descended into downtown New York and crashed into a building in a fiery blaze. At least, that’s what happens in the shocking nightmare sequence that evokes thoughts of 9/11 in the opening of Sully, director Clint Eastwood’s account of what actually happened: the pilot famously landed his plane on the Hudson River, which resulted in all 155 passengers surviving, and led to widespread praise for Sully as an American hero. In fact, Sully’s prologue is just the pilot’s nervy dream following the incident, and it’s the most involving sequence in an otherwise straightforward film that unabashedly reveres its protagonist.

Tom Hanks plays the titular role with an immediate dignity only his level of onscreen persona can bring; his authority lends an air of poise and humanity to the character, who questions whether he made the right decision. At first, Eastwood resists showing his audience what happened and instead takes a nonlinear approach, beginning with Sully at the center of a National Transportation Safety Board investigation, and then periodically flashing back. Alongside Skiles (Aaron Eckhart), Sully endures questions from a committee (Mike O’Malley, Anna Gunn, Jamey Sheridan) looking for someone to blame. The audience hears the details of what happened from the pilot, but also how the flight computer contains evidence that doesn’t corroborate his statements. At the same time, throughout the investigation in New York, Sully expresses his doubts via phone conversations back home to his wife, Lorrie (Laura Linney).

Screenwriter Todd Komarnicki takes liberties with the real-life story to pad the runtime and create a conflict; otherwise, the 208-seconds following the bird strike would not have enough material for a feature-length picture. After all, despite the potential dangers of Sully’s landing, and the risks to his career in the subsequent investigation, all turned out rather well. Since most people are familiar with the events from just seven years ago, the happy outcome doesn’t produce the overwhelming satisfaction a lesser-known or fictional story would have. For example, Robert Zemeckis’ Flight (2012) told a very similar story, presented a far more dynamic and interesting character, and resulted in a much more involving experience for the audience. To compensate, Komarnicki manufactures an accusatory tone for the investigators, suggesting Sully somehow avoided crucifixion when his decision to land on the Hudson proves to be correct.

The film’s minor conflict resides in Sully’s uncertainties, allowing Hanks to deliver some nice moments of self-doubt before the big hearing scenes late in the film. Beyond these scenes of Hanks augmenting the character with his talent, Sully seems rather conflict-free and only mildly compelling. Again, given that most of us know the outcome, the film’s attempts to generate pressure on Sully contain less tension than Eastwood seems to think they will. The investigators talk about how computer models show Sully was incorrect, and later, test pilots demonstrate the same in simulated flights. In showing us Sully’s fateful flight over and over again from various perspectives, the film seems to want us to doubt Sully, which we never do. It’s hard to have doubts about the man when, throughout the film, Eastwood also shows him receiving spontaneous hugs and admiration for his heroism from random New Yorkers (Katie Couric among them).

Of course, what Sullenberger did was astounding, but he’s the first to admit to several media outlets that he’s not a hero: “I was just doing my job.” Then again, Sullenberger and Jeffrey Zaslow wasted no time writing a book about what happened, having released Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters just a few short months after the so-called “Miracle on the Hudson”. (Even Skiles mentions in the film that Sully has a knack for marketing.) The film’s approach, much like Eastwood’s work on American Sniper (2014), operates in hero worship and dignified appreciation of an American hero—as well as the response team who recovered passengers from the floating plane. Eastwood’s film seems to applaud everyone involved in the situation. In the postscript, Sully venerates New York: “The best of New York came together. It took them 24 minutes.”

The entire picture contains Eastwood’s confident, easygoing touch, delivering a solid formal presentation. The director’s frequent collaborator Tom Stern once again lenses in muted colors, reflecting the overcast skies of the cold January landing. But Sully doesn’t develop or expand upon the story in any meaningful way, leaving a 96-minute feature feeling strained for material, filling out the runtime with throwaway asides amidst the flight’s passengers and flight crew. Of course, the water landing remains the film’s centerpiece and a stunning few minutes of spectacle, on par with the tsunami sequence from Eastwood’s underrated Hereafter (2010). But the narrative sheds no new light on the story or character. Fortunately, Eastwood made a wise casting choice, and Hanks makes the transparent qualities of Sully work more than they should.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review