Suffragette

By Brian Eggert |

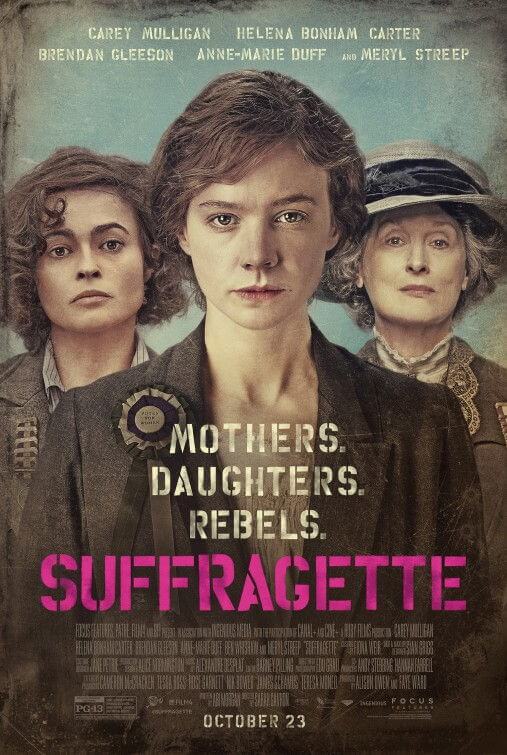

An important and topical subject matter receives a disappointingly conventional treatment in Suffragette, an historical account of daring English women who became foot soldiers in a battle for equal rights in the early nineteenth century. Filled with harrowing moments of rebellion and civil disobedience, as well as melodramatic scenes reflecting the tough home lives for many of these average working women, the film lacks an overall dramatic arc that would tie it all together. Director Sarah Gavron and screenwriter Abi Morgan last collaborated on 2007’s Brick Lane; however, their meaningful history lesson here is burdened by a formulaic narrative and empty core. Strong performance from Carey Mulligan and Helena Bonham Carter aside, Suffragette plays it safe when the real people involved did anything but.

To draw worldwide attention to the women’s suffrage movement, Emily Wilding Davison famously stepped in front of King George V’s horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913, sacrificing herself to her cause. But rather than tell her radical and at times tortuous story, Morgan creates a fictionalized composite designed to be the audience’s safer entry point into the movement. As a laundress, 24-year-old Maud Watts (Mulligan) endures scarring chemicals, hard labor, and the sexual advances of her boss. At home, her husband (Ben Whishaw) and young son George (Adam Michael Dodd) live a poor life. Around London, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) has taken to brick throwing and protests to receive the vote, their movement heading a toward militant campaign by order of their chief, Emmeline Pankhurst (appearing in a brief cameo). As Maud finds herself drawn into the fight, Davison, played by Natalie Press, remains on the margins of Maud’s story.

At first reluctant to join their cause, Maud eventually suffers prison, abandonment, and the loss of her son once she begins collaborating with a pharmacist and loyal Pankhurst soldier Edith Ellyn (Helena Bonham Carter). We see Maud participate in carefully coordinated attacks on mailboxes and communication lines, a hunger strike in prison, and all the other trappings of political rebellion—including a terrorist bombing of statesman’s home. Meanwhile, men sneer at these women, and a local authority (Brendan Gleeson) spies on them to track their activities, adding a layer of spy-thriller paranoia to the proceedings. But the story of when the movement achieved its victory is overshadowed by the emotional draw of Maud’s personal life, none of which receives any kind of satisfying closure for the audience. At the same time, Maud undergoes an extreme amount of punishment for her beliefs, but in real-life, Davison suffered far worse.

Factoid titles at the opening and close of the film set the historical stage, while Maud’s arc seems like only a small part of a much larger legacy the audience doesn’t get to see. Nevertheless, Mulligan’s performance is an effective balance between a lifetime of oppression and an inner outrage that boils over in time. Her scenes across from Gleeson’s conflicted but dutiful enforcer are the few standouts in the film. On a level of pure craftsmanship, Suffragette deserves recognition for its detailed costumes by designer Jane Petrie and the impressive period-detail achieved by production designer Alice Normington. Cinematographer Edu Grau captures it all in muted tones, employing handheld techniques that at times feel overly wobbly for such a straightforward story.

In a time where female actors such as Emma Thompson and Jennifer Lawrence are speaking out about the enduring trend of lesser wages for women in Hollywood, a film like Suffragette should incite one to get up, cheer, and then make demands for change. But instead, the audience receives a dull finale that feels softened by its preference for Maud’s story over female sufferage. Even the advertising campaign made some rather questionable and sexist choices, adorning dreary character posters with bright pink lettering, because, you know, girls like pink. That kind of broad thinking drives this film and helps deliver a standard historical picture, not unlike Morgan’s screenplay for The Iron Lady (2011), another toothless account of an important female figure. When an issue such as women’s right to vote caused such fervor, it’s a shame to see a film so devoid of passion about the subject that it fails to provoke, inspire, or challenge its viewers.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review