Reader's Choice

Street Trash

By Brian Eggert |

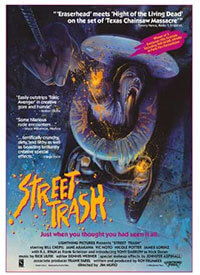

Around the time an unsuspecting bum inadvertently urinates on another, causing the pee-victim to chop off the offending man’s penis, while at the same moment, not far away, a would-be rapist engages in necrophilia with the corpse of a gang-rape victim, I decided Street Trash wasn’t my cup of tea. Or maybe it was the scene when a cop who looks like a professional wrestler gags himself to vomit on the mob hitman he just knocked out, and the vomit looks like bloody oatmeal. Then again, it might’ve been how every woman in the film is either a prostitute, a rape victim, or an attempted rape victim. The exploitative quality of transgressive cinema like this offers a riotous good time for some, but it’s a pure provocation to me. It’s not that I don’t understand why the filmmakers have embraced an offend everyone stance, nor do I fail to see the value in this 1987 cult classic as a work of anti-establishment filmmaking. However, there comes a point where the process of intentionally subverting the boundaries of good taste becomes tiresome to me. Of course, cult cinema is all about identifying and pushing the limits of discomfort—the more the audience squirms, feels offended, or says “Ewww,” the better. About halfway through Street Trash, I was numb to the approach. The film was trying to provoke a reaction out of me, but I could see its agenda. From that point on, all I saw was a desperate attempt to get a reaction. My response to the film is the same with a bully or noisy child; I just roll my eyes and ignore it.

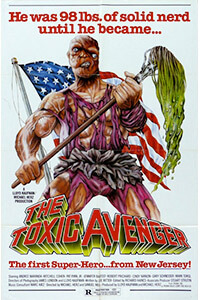

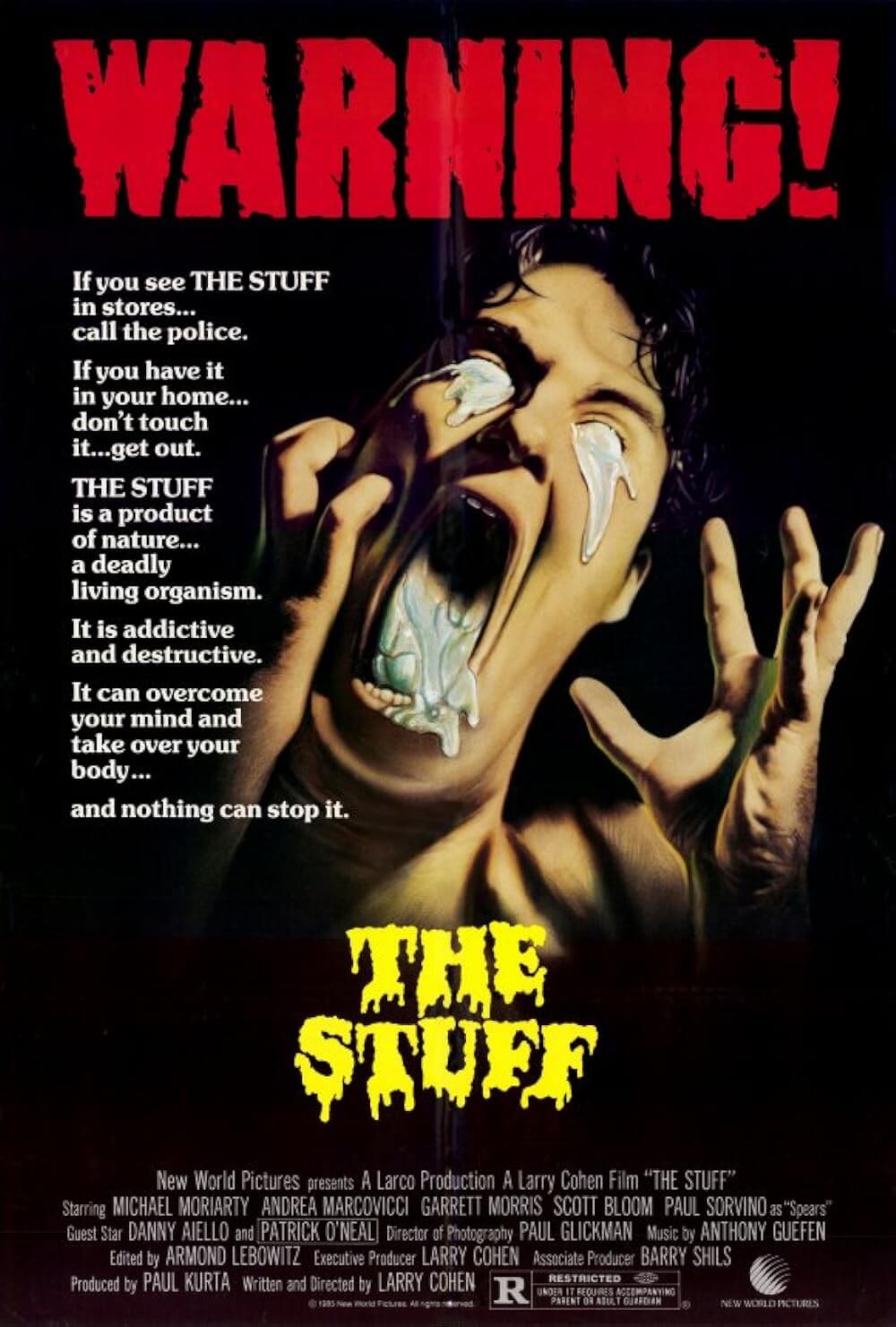

Made at the same pitch as a Troma product, Street Trash was distributed theatrically by the schlockmeisters at Lightning Pictures, an offshoot of Vestron Video, a company that thrived in the early home video market. Companies like Lightning and Vestron knew that rentals could mean massive profits. So their goal became to produce movies whose VHS box art would convince some teenager or horror fanatic to rent a tape from their local video store, gas station, or marketplace. Meaning, they produced culty horror-comedies like Blood Diner (1987) and C.H.U.D. II: Bud the C.H.U.D. (1987). If one associates Hollywood cinema with roughly the same cultural significance as a stage play, then cult cinema, as observed by scholar David Church, has the quality of a sideshow that appeals to “the edges of normative society by playing in culturally low venues” such as video rental outlets or midnight madness screenings. Based on a short student film made by director Jim Muro, Street Trash has lasted over thirty years in the cult realm. Almost experimental in its gross-out and unorthodox appeal, it tries desperately to conform to nonconformity that it can only be appreciated as an ironic attempt at subversiveness. Of course, its displays of melting derelicts, exploited women, and dark comedy prove reactionary, set in the predictable style of excess found in The Toxic Avenger (1984), The Stuff (1985), and Society (1989). It works against Hollywood’s aesthetic traditions to target an alternative but no less defined demographic of cultists drawn to deviation.

The difference between Street Trash and other titles deemed “melt movies” is that most in this subcategory of horror tend to have a narrative with characters worthy of our attention. The Toxic Avenger may have been nasty, but it was a rather conventional superhero yarn; The Stuff combined a conspiracy thriller with a critique of the capitalist food industry; and Society aimed its gooey orgy at the limited gene pool of the upper classes. Muro’s film might be considered exceptional for its utter lack of sympathetic characters or compelling plot. The story follows a liquor store owner in Brooklyn who unknowingly sells toxic booze called Tenafly Viper to a group of local hobos, resulting in a series of meltdowns, overhead drippings, and bodily explosions. Meanwhile, Bronson (Vic Noto), a warped Vietnam veteran with PTSD, oversees a collection of junkyard lackeys who appear comically dirty, as if auditioning to become chimney sweeps. At one point, they crawl through the garbage—in a sequence shot to resemble the climax in Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932)—to gang rape and murder a drunken woman. This draws the attention of a local cop (Bill Chepil), setting up a showdown. The result aims for maximum exploitation, and it’s all a bit erratic and unfocused, lacking any narrative thrust or reason to care.

Muro seems to embrace what Jeffrey Sconce termed “paracinema,” a category of cult film that is “less a distinct group of films than a particular reading protocol, a counter-aesthetic turned subcultural sensibility devoted to all manner of cultural detritus.” The basic idea is to rebel against everything, try to offend everyone, and thereby endear cultists to the film’s sense of rebellion. Films like Street Trash set up an oppositional “us versus them” relationship between the cult viewer and their choice to embrace so-called trash cinema over the traditional or mainstream. It’s a subculture of viewership that embraces deviancy, transgressiveness, gory spectacle, and sexual titillation—in the same manner of the Marquis de Sade, who wrote stories designed to sexually arouse, embrace taboos, or disgust the reader, while at the time eviscerating the power dynamics of the dominant culture. These methods present a contrast to Hollywood standards that prove more mannered, accessible, and commercial-minded. Sconce notes, “The paracinematic audience recognizes Hollywood as an economic and artistic institution that represents not just a body of films, but a particular mode of film production and its accompanying signifying practices.” The cult audience, then, rallies against the institution, which is both ordered and repressive, and it celebrates deviations from Hollywood’s shaping of the culture.

Some paracinema braves social material that mainstream movies refuse to confront. By addressing contemporary issues that prove relatable for the masses as the culture changes, the movies cease to be paracinematic. As Sconce notes, “Paracinematic taste involves a reading strategy that renders the bad into the sublime.” Occasionally, this strategy normalizes trash cinema, and the cult becomes mainstream. Consider how George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead may seem tame by today’s standards. Still, in 1968, its portrayal of cannibalistic ghouls and backwoods vigilantes spoke to issues of violence and racism in America as few films could. In Romero’s case, what was seen as “bad” or unconventional has gradually transitioned into today’s canon. As the decades pass, Romero’s splattery works have gone from midnight madness fare to essential reflectors of their day. Audiences have grown desensitized thanks to Hollywood’s assimilation of zombies into mainstream entertainment. The same cannot be said of Street Trash, which does not evoke thoughtful consideration. But the film does remain just as infractional, if not for the rubbery, melty effects and lack of straightforward narrative, then for its treatment of necrophilia, race, and various exploitative uses for women.

One could argue that screenwriter Roy Frumkes sought to address social anxieties about vagrancy and crime in New York if one so desired. At the time, crime rates were higher than ever, and films like Escape from New York (1981) and Friday the 13th, Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan (1989) addressed the public’s trepidation about the unsafe streets by portraying them as garbage-strewn and teeming with a criminal element. Frumkes’ approach could mock the mainstream opinion that the homeless are dangerous alcoholics, rapists, and murderers who carry disease and prey on others. When Muro exaggerates these tendencies in Street Trash through rapey characters and gooey effects that outperform even The Toxic Avenger’s yuck factor, he thumbs his nose at the establishment. Does the film manage a cohesive argument against low opinions about the homeless and street crimes? Not really. Does it offer the least amount of pathos? Not at all. Street Trash is best when it’s showcasing the gleefully gross special FX work. In one sequence, an overweight drifter guzzles down a bottle of Tenafly Viper. He expands like a balloon, leading to a memorable explosion to rival the detonating head in Scanners (1981). Individual moments like this inspire a wowed chuckle at the gross-out heights. Unfortunately, everything in between these moments of incredible gore proves quite tedious.

Street Trash is an object of cult fascination whose status has been around from the underground VHS market of the 1980s and 1990s to today’s DVD/Blu-ray boutique labels. The optimal fuzzy video presentation of yesteryear has been replaced with a sharp restoration, even though it probably works better when screened on a crummy VHS bootleg—preferably late at night in your parents’ basement, alongside a few friends willing to laugh at just how far it’s willing to go. Perhaps as a 13-year-old, I might have enjoyed the film’s various attempts at grotesque comedy: the farts in the face; the absurd fight scenes; and the array of multicolored slimes oozing from Tenafly Viper victims—captured in bright neon blues, greens, purples, yellows, and oranges. Today, I appreciated the fluid, roving camerawork by David Sperling (a confident visualist, Muro went on to become a Steadicam operator for directors like James Cameron and Kevin Costner). I also respected how few boundaries the film sets for itself. But unlike other titles under the paracinema umbrella, I wasn’t cheering on its rebellion; I was waiting for it to be over. Though Muro deviates from the Hollywood standard to deliver something deliberately offensive, his methods prove so anti-everything that the relationship between Street Trash and its opposition feels less like a commentary on the mainstream and more like a childish prank that asks, “How far can we go?”

Whether it’s Lars von Trier’s recent work or the cult of melt movies, I tend to respond with a shrug when filmmakers attempt to goad me into a reactionary response. I don’t get offended; I just feel bored at the obvious effort to incite. It’s more respectable when a film uses a democratic way of getting under my skin by establishing some measure of emotional investment before turning on me. Filmmakers ranging from Michael Haneke (Funny Games, 1997 and 2007) to Stuart Gordon (Re-Animator, 1985) understand that a filmmaker can work within classical tropes and then break them to ambush the audience and provide a real shock to the system. Street Trash feels so determined to offend every demographic that it abandons any relationship with audiences besides an ironic one. It expects the audience to cherish how it resists the traditional. And while I felt the initial melting, where a vagrant accidentally flushes himself down the toilet after drinking toxic sauce, appealed to my appreciation for out-there effects, the rest seemed loud and pointless—which is exactly the point, albeit one I don’t care to celebrate.

(Note: This review was suggested on Patreon by Ann. Thanks for your continued support, Ann!)

Bibliography:

Church, David. “Freakery, Cult Films, and the Problem of Ambivalence.” Journal of Film and Video, vol. 63, no. 1, 2011, pp. 03–17. JSTOR, jstor.org/stable/10.5406/jfilmvideo.63.1.0003. Accessed 1 Mar. 2021.

Mathijs, Ernest, and Xavier Mendik, editors. The Cult Film Reader. Open University Press, 2008.

Sconce, Jeffrey. “’Trashing’ the Academy: Taste, Excess, and an Emerging Politics of Cinematic Style.” Screen, Volume 36, Number 4, 1995.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review