Straw Dogs

By Brian Eggert |

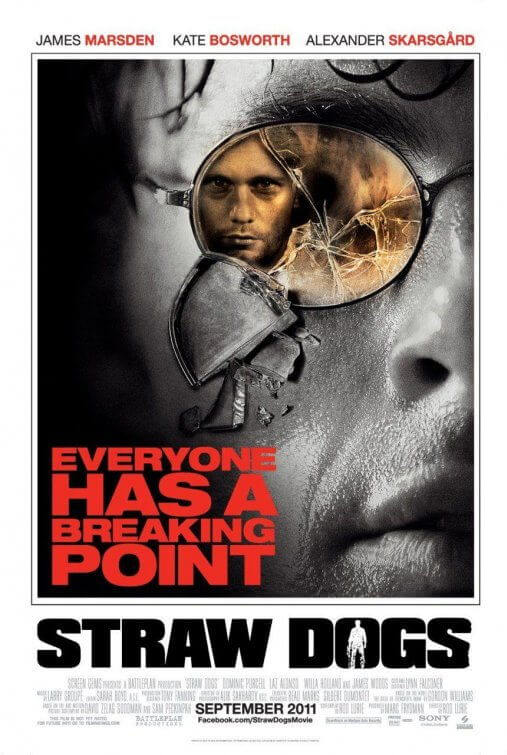

A wholly unnecessary Hollywood treatment of Sam Peckinpah’s unsettling and controversial 1971 original, Rod Lurie’s remake Straw Dogs conventionalizes one of the most hotly debated films in cinematic history by removing any hope for diverging interpretations. Nuance and layered characterizations have no place in what becomes a typical home-invasion thriller, simplified for mass consumption. Audiences unfamiliar with “Bloody” Sam’s original—a film best appreciated from a safe distance—may find the experience mildly diverting if they can tolerate a rape scene and a finale wrought by amped-up violence, but viewers confronted by the original will have little to debate or discuss afterward. Except, of course, how Lurie’s changes to David Zelag Goodman and Peckinpah’s original script diminish the material.

For the uninitiated, Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs fueled feminist protests by representing an archetypal example of male-chauvinist filmmaking. In the film, a husband and wife couple played by Dustin Hoffman and Susan George move to the outskirts of her home village in England, where he’s emasculated and she’s ogled by local yokels. Domestic scenes show a distinct marital discord that elevates the tension, leading to a rape, and subsequent violence when townspeople raid their home. Hoffman defends the homestead and, in turn, earns his manhood by embracing his natural, manly instinct for violence. George remains merely a wife, her character controversially passive during her rape scene, but she’s layered through a clever performance nonetheless. Renowned critic Pauline Kael called it “a fascist work of art,” and she was, in a way, all too correct.

Adopting an unfortunate and rather obvious shift in setting, Lurie’s version moves the action from England to the Deep South, a Bible-pumpin’, football-playin’ town called Blackwater, Mississippi. The shift takes advantage of prejudices against southern-fried hillbillies and their stereotyped propensity for intolerance (somewhere, Tucker and Dale are crying out in protest). Lurie also changes the Sumners’ occupations: David from a mathematician to a screenwriter, and Amy from a housewife to a TV actress. At any rate, David and his wife (James Marsden and Kate Bosworth, reteamed after Superman Returns) arrive in the backwoods of her hometown; he’s instantly out of place in his Harvard t-shirt but naively optimistic, and she’s remembering why she left. A barn on their property needs repairs and they hire a crew of good-ole-boys, led by Amy’s high school sweetheart Charlie (Alexander Skarsgard), to fix ‘er up. The local workers flex their passive-aggressive muscles and test David’s pacifism, walking into the Sumner’s house whenever they want, blasting loud music, and eyeballing Amy—whose skimpy outfits do nothing to deter their behavior, even if she takes offense to the implication that she’s “asking for it.”

Where Lurie’s film fails is creating the same palpable tension between the married couple as the one that exists between the Sumners and the locals. Peckinpah’s version suggested a divergence in the marriage that increased strain on all fronts, and which questioned Amy’s intentions in her unconscious flirtations with her former lover. Lurie’s Amy is more direct, even after the rape scene, which contains none of the curious non-reactions on Amy’s part as in Peckinpah’s version—it’s just a straightforward scene, meant to depict a traumatic event rather than make us analyze its levels. When the conflict escalates into a full-on attack, headed by James Woods’ bloodthirsty former football coach, David finally counters Amy’s accusations of cowardice by fighting back. Using the same assemblage of weaponry with the same results, Lurie repeats Peckinpah’s notorious shotgun-to-the-foot and beartrap sequences to nominal effect.

Each of the performances play out in predictable ways, Lurie never allowing them to grow naturally or divert much from the original interpretations. Instead of playing subtle and frustrating games, Bosworth’s unsympathetic Amy pushes David right along the path to violence by calling him a coward. Bosworth renovates her role into a hard case, whereas George’s drony housewife brought about certain subtextual questions that sparked debate about the original’s meaning. However, no one will debate the characters’ intentions thanks to Lurie’s cut-and-dry presentation. Marsden, most commonly known as Cyclops from the X-Men franchise, fills Hoffman’s shoes well enough but (once again) doesn’t make an impression beyond his glasses. The football coach is one of Woods’ most pronounced roles in years, but it’s a typical hotheaded bastard role for this type of movie. True Blood heartthrob Skarsgard makes a believable, intimidating redneck, being about six feet taller than Marsden. Most embarrassing is Dominic Purcell’s almost comic take on Niles (originally played by David Warner), the disturbed local whose Of Mice and Men moment incites the finale’s attack.

Normally associated with talky political dramas like The Contender and Nothing But the Truth, Lurie’s direction shows promise early on during tense exchanges of dialogue, but it falls apart when things go south, so to speak. In the final siege, he employs standardized action scene tricks like choppy editing and tight zooms on bloody impacts, and the result is full of tension but far too close to Peckinpah’s take—all except for the ending, which omits the original’s soul-searching drive back to town. In its place, the film ends when David has killed off the attackers, glorifying his victory. But Peckinpah wanted his viewers to find the violence abhorrent and circumstances uncomfortable; he pushed the limits so that, when it was over, we would dwell on our feelings of catharsis toward David’s outburst with revulsion and self-reflection.

Lurie means for us to be caught up in the excitement despite ourselves, but he leaves us with nothing to regret afterward. Chances are those who were confronted by Peckinpah’s film will find Lurie’s one-dimensional take perhaps too narrow, the villains too deserving, and the conflict far too black-and-white. Peckinpah’s film took place entirely in the gray zone. Lurie brings nothing new to the material except a fresh cast and younger audience (always the purpose of remakes), and strips away far too much for the resulting film to have an impact. Viewers walk away having watched a serviceable, undemanding movie. And for some, this remake will be an effective potboiler, above all for those untried on the original. But for those who have endured Peckinpah’s film, this is like trying to notice a mild toothache after being shot in the face.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review