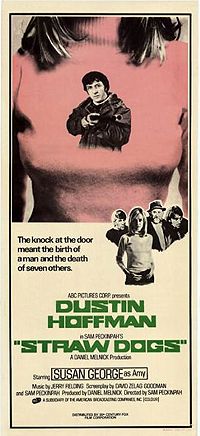

Straw Dogs

By Brian Eggert |

Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs is a film about man’s ravenous appetite for violence, a natural instinct passed down from the whole of human history, itself so often written in blood. Violence was one of many themes pulsating through The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah’s archetypal Western from 1969; but this film, released two years later, uses violence as its thematic centerpiece, forcing its audience to confront man’s innate desire for and repression of violence. This desire, Peckinpah argued at the time of the film’s release, is frequently defended or justified through false motivations to protect one’s property or one’s wife, but violence has more to do with our “primitive thirst for blood.” Upon its release, Straw Dogs was both attacked as a misogynistic tirade and lauded as a cautionary tale that warned about the costs of violence. Today it stands as a precarious landmark to the power of cinema as an interpretive art form.

The film opens as David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman) and his British wife, Amy (Susan George), have moved from America into a farmhouse in Amy’s hometown village in the English countryside. He’s a mathematician and professor whose work consumes him; she’s likely a former student of his, and she tests their love every time David chooses his study over her need for attention. Marital resentment runs wild, as neither partner will relinquish their tension and, in fact, opt to antagonize each other. When she can’t get attention from David, Amy takes to flirting with the workmen who are repairing the Sumner’s farmhouse. A child of the Sixties, she walks about brawless, and Peckinpah’s camera stops to ogle her from the workmen’s point of view. Her flirtations escalate the workmen’s jealousy of the smartypants American and his beautiful wife, and they begin taunting him. Playful jibes become threatening displays from which David always backs down; rather than stand up for himself, he tries to become their friend. And it seems they go along with his plan when they invite him to go hunting in the woods.

While on their faux hunting expedition, the workmen abandon David, and hours pass before he realizes he’s been ditched. Back at the house, one of the workmen, Amy’s former lover Charlie (Del Henney), reminisces with her about the old days before forcing himself on her. Amy resists at first, but all of her contained resentment comes pouring out, transforming a rape scene into one of sudden passion. That is, until fellow villager Norman (Ken Hutchison) enters, and Charlie offers Amy up to his comrade, holding her down as Norman rapes her. There’s a clear disconnect during this scene. Audiences never quite know how to reconcile their emotional reaction to their intellectual one, which, of course, is the point. The scene itself, as well as the depiction of Amy (and the concentration on her breasts), most commonly serves as a prime example of male-chauvinist fantasy in feminist theory, the smoking gun against Hollywood’s representation of women as sex objects just asking for, and not completely opposed to, a rape that blurs the borders between pain and pleasure—a vile example of that old myth that a woman never knows what she wants until it’s given to her. That Amy never tells David what happened is further testament to this theory and further evidence that David is incapable of protecting “what is his.”

Through the rape scene, David stands aimlessly in an empty field. Hoffman’s role defies typical “hero” descriptions by simply being the least objectionable character onscreen, as any hope for sympathy is lost on characters driven solely by their hostilities. David finally “becomes a man” when he defends his home from a fleet of drunken, raiding workmen, who later converge on the farmhouse to lynch a suspected sex criminal, local idiot Niles (David Warner), who David and Amy brought home after accidentally grazing him in their car. The mob goes blood simple and forgoes any hope of moral resolution, so they attack. Only through killing, the act of violence in a most grotesque form, can David shed his intellectual façade and embrace man’s true calling. Thus, in the end, after David has killed off all of the invaders with an array of homespun weaponry (whiskey heated on the stovetop, a shotgun, a massive beartrap, etc.), he does not stand by his wife. Now he identifies more with Niles—both being men so unable to contain their impulses that they have become outcasts and monsters—and leaves Amy there to drive Niles home. “I don’t know my way home,” says Niles. David just smiles and remarks, “That’s okay. I don’t either.”

Through the rape scene, David stands aimlessly in an empty field. Hoffman’s role defies typical “hero” descriptions by simply being the least objectionable character onscreen, as any hope for sympathy is lost on characters driven solely by their hostilities. David finally “becomes a man” when he defends his home from a fleet of drunken, raiding workmen, who later converge on the farmhouse to lynch a suspected sex criminal, local idiot Niles (David Warner), who David and Amy brought home after accidentally grazing him in their car. The mob goes blood simple and forgoes any hope of moral resolution, so they attack. Only through killing, the act of violence in a most grotesque form, can David shed his intellectual façade and embrace man’s true calling. Thus, in the end, after David has killed off all of the invaders with an array of homespun weaponry (whiskey heated on the stovetop, a shotgun, a massive beartrap, etc.), he does not stand by his wife. Now he identifies more with Niles—both being men so unable to contain their impulses that they have become outcasts and monsters—and leaves Amy there to drive Niles home. “I don’t know my way home,” says Niles. David just smiles and remarks, “That’s okay. I don’t either.”

Based on Gordon Williams’ story The Siege of Trencher’s Farm, Peckinpah was asked to change the title because it sounded too much like a Western, the only genre Peckinpah had explored on film thus far. The director lifted his title from Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu’s The Book of 5,000 Characters, from a passage that placed “straw dogs” between Heaven and Earth, caught between two ideals, always divided in a torturous existence. In this ambiguous zone, where the screenplay adapted by David Zelag Goodman (with constant rewrites by Peckinpah, producer David Melnick, and later Hoffman) takes place, the protagonist is likewise divided between his intellect and violent impulses. Reactions to the film were and still are equally polarized between those who grasp that Peckinpah was after more than an exploitation of masculine ideas, and those who see a celebration of man’s violent nature.

To understand Straw Dogs, or perhaps endure is a better word than understand, a viewer must first appreciate the career-long duality behind Sam Peckinpah’s persona as an auteur director, and his use of violence as a confrontational device in film. Peckinpah himself was a quiet, grave man filled with weighty ideas, but also one subject to bouts of depression and manic alcoholic rages. This duality, the push and pull between sobriety and drunkenness, between his early career’s collaborative work and his late-career nihilism, informs his greatest pictures. The Wild Bunch, for example, was censured for its abhorrent bloodshed, but not by those who identified that film as a probe into and reaction to why audiences crave a Western hero who kills the bad guy. Peckinpah challenges an audience to sit through the final, glorious, horrifying shootout at the end of The Wild Bunch and the violent acts at the end of Straw Dogs. Although he was known to laugh if audiences ran out of the theater during violent scenes at screenings of his films, he was proud when people stayed behind. He knew, of course, that those who remained undoubtedly felt no good about their choice, but they opted to stay and allow themselves to be confronted.

To understand Straw Dogs, or perhaps endure is a better word than understand, a viewer must first appreciate the career-long duality behind Sam Peckinpah’s persona as an auteur director, and his use of violence as a confrontational device in film. Peckinpah himself was a quiet, grave man filled with weighty ideas, but also one subject to bouts of depression and manic alcoholic rages. This duality, the push and pull between sobriety and drunkenness, between his early career’s collaborative work and his late-career nihilism, informs his greatest pictures. The Wild Bunch, for example, was censured for its abhorrent bloodshed, but not by those who identified that film as a probe into and reaction to why audiences crave a Western hero who kills the bad guy. Peckinpah challenges an audience to sit through the final, glorious, horrifying shootout at the end of The Wild Bunch and the violent acts at the end of Straw Dogs. Although he was known to laugh if audiences ran out of the theater during violent scenes at screenings of his films, he was proud when people stayed behind. He knew, of course, that those who remained undoubtedly felt no good about their choice, but they opted to stay and allow themselves to be confronted.

Peckinpah’s approach to Straw Dogs exists somewhere between two other similarly themed films: Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring and Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left. Both involve rape and violent retribution (Craven’s film was actually based on Bergman’s). The former weighs the moral implications of violence through open dialogue, a philosophizing protagonist compelled toward revenge but beset by his religious convictions that teach him not to kill. The latter, in both its original and remake forms, follows an uninhibited outburst of vengeance by two parents after their daughter is brutally attacked. Peckinpah’s film doesn’t engage in Craven’s mindless abuse of raw violence, at least not completely; the film’s slow build and final coda indicate a more significant purpose behind the story. But he doesn’t have David pondering ethical concerns in any meaningful way prior to his own film’s eruption of violence, either. The story plays out, and it’s up to the audience to decide what it means.

As a result, Straw Dogs works better as an art piece ruminating on violence as neither “good” nor “bad” but merely a fact of “man’s” existence. Naturally, the majority of audiences won’t see it that way, and unfortunately, that’s why Peckinpah’s film, though controversial and confronting and an important work of art, fails for so many viewers, myself included. There is a great difficulty that comes with watching irredeemable people do horrible things and have horrible things done to them, and then being told that “chaos reigns” (to quote another divisive film, Lars von Trier’s Antichrist). Cinema is at its best when art and entertainment converge into something accessible, yet thought-provoking. Here, the entertainment component is almost nonexistent, whereas the art component meets its audience with an unforgivably aggressive confrontational purpose. So while I understand this film and welcome its message, it’s a film that I wouldn’t want to revisit, whereas The Wild Bunch redeems its violence by way of friendship or the moving nobility among its thieves and killers. The intellectual part of me knows this film deserves a four-star review, but the emotional part rejects its interpret-as-you-will structure and its refusal to offer characters to which we can attach. In other words, I admire Straw Dogs, but from a safe distance.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review